Archlog

Cover, founded by Alexis Rivas & Jemuel Joseph, featured in Archinect

POSTED ON: February 18, 2021

© Cover Technologies, Inc.

The work of School of Architecture graduates Jemuel Joseph and Alexis Rivas, both AR’16, has been featured in Archinect, in a piece addressing their unique approach to productizing prefabrication. Co-founders of Cover, a company that designs, manufactures, and installs backyard homes in Los Angeles, Joseph and Rivas challenge the inefficiencies and high costs of conventional construction, questioning whether the prefabrication of homes in factories can be streamlined to increase productivity and reduce costs. The premise of Cover is that the entire manner in which homes are prefabricated needs to be completely reconsidered.

Rivas, having learned from his previous work in construction and prefabrication, and Joseph, who specializes in web development and 3D animation, combined their skills and set out to redesign the methods and materials of prefabrication from the ground up. Understanding the need for technology-driven mass-customization, the two reached out to engineers from companies, including Tesla, SpaceX, and Apple, that use production lines to manufacture their products. The resulting collaboration across disciplines yielded a technology company that builds homes, rather than a conventional architecture firm.

Alexis and Jemuel credit their Cooper Union education for shaping their problem-solving skills. In reflecting on their efforts, Dean Tehrani noted “Alexis and Jemuel demonstrate how their pedagogical challenges involved problems of making that, through their ingenuity, could be scaled up to impact production at the industrial level. In them, I see a conceptual precision — what I like to think is a cornerstone of Cooper culture — that has the ability to impact thinking that can be transposed from the academic realm into practice, indeed changing practice entirely as we know it today.”

Summarizing the Cover experience to date, Alexis noted “Home building is slow, expensive, unpredictable, and usually low quality. At Cover, our mission is to make thoughtfully designed and well-built homes for everyone. Homes that improve people's daily lives, reflect our modern way of living, embrace progress, and are uncompromising in their design and performance... What we’re doing is using technology to raise the bar for conventional construction so that this kind of thorough design work can be applied to all homes — not just

the ultra-high-end segment.”

Anna Bokov Publishes New Book

POSTED ON: February 16, 2021

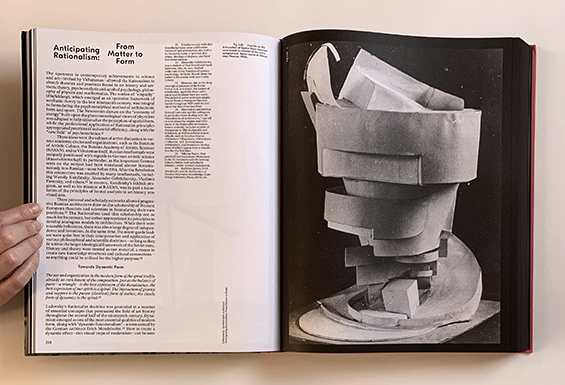

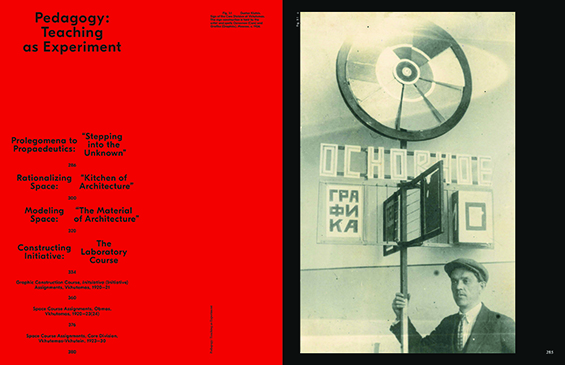

'Space' Course Classroom, 1927 | Museum of the Moscow Architectural Institute

Assistant Professor Adjunct Anna Bokov has just published Avant-Garde as Method (Park Books, 2020), a groundbreaking study on the early Soviet Union's Higher Art and Technical Studios, known as Vkhutemas. Though ten times the size of the Bauhaus and equally influential, Vkhutemas was, until recently, largely forgotten by art and design history. Bokov’s comprehensive and richly illustrated volume—recently reviewed in Architectural Record—is the definitive reference work on a pioneering school and pedagogy that has had a lasting influence on Modernism.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s Vkhutemas adopted what it called the “objective method” to facilitate instruction on an immense scale. The school was the first to implement mass art and technology education, which was seen as essential to the Soviet Union’s dominant modernist paradigm. Bokov’s work explores the nature of Soviet art and technology education, showing that Vkhutemas combined longstanding academic ideas and practices with nascent industrial era ones to initiate a new type of exploratory pedagogy—one that drew its strength from continuous feedback and exchange between students and educators. After elaborating on the ways that Vkhutemas challenged established canons of academic tradition by replacing them with open-ended inquiry, Bokov shows how this inquiry was articulated in architectural and urban projects in the school’s advanced studios.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s Vkhutemas adopted what it called the “objective method” to facilitate instruction on an immense scale. The school was the first to implement mass art and technology education, which was seen as essential to the Soviet Union’s dominant modernist paradigm. Bokov’s work explores the nature of Soviet art and technology education, showing that Vkhutemas combined longstanding academic ideas and practices with nascent industrial era ones to initiate a new type of exploratory pedagogy—one that drew its strength from continuous feedback and exchange between students and educators. After elaborating on the ways that Vkhutemas challenged established canons of academic tradition by replacing them with open-ended inquiry, Bokov shows how this inquiry was articulated in architectural and urban projects in the school’s advanced studios.

Professor Anthony Vidler notes of Avant-Garde as Method, “This book will be a revelation to scholars and the general public, positioning Vkhutemas as an equal pedagogical force to the Bauhaus in the shaping of the Modern movement in architecture and design.” The School of Architecture is also pleased to be sharing Bokov’s work via Vkhutemas: Laboratory of the Avant-Garde, 1920 – 1930, an exhibition planned for the Arthur A. Houghton Jr. Gallery in early 2022.

Tags: Anna Bokov

Young & Ayata Receives 2021 AIANY Design Award

POSTED ON: January 26, 2021

Young & Ayata, a Brooklyn-based design office co-founded by Assistant Professor Michael Young, has received a 2021 AIANY Design Award for its recently completed DL1310 Apartments in Mexico City. Developed in partnership with a local collaborating firm, Michan Architecture, the project is a four-story multifamily building with seven one-to-two bedroom apartments above a basement parking garage. The client’s desire to maximize the building’s footprint and height prompted the designers to focus on its apertures:

"In order to allow light, view, and ventilation to all sides of the building, a scheme was developed to manipulate the windows into something familiar yet subtly strange. The rectangular windows are rotated into the building’s facade, resulting in two ruled surfaces at the top and bottom and transforming the window into an inverted trapezoidal bay. As the windows rotate in, the slabs appear to pull at the head and sill. This results in a facade that is both extremely blunt in its flatness and is also a dynamic bas-relief of smooth, undulating shadows. These windows also produced different interior moments as the shifting facade met the standardized unit layout. Views out from the interior became small events of forced oblique perspective as one looked both out and down the street at the same time, making each unit unique as it approached the enclosure."

"In order to allow light, view, and ventilation to all sides of the building, a scheme was developed to manipulate the windows into something familiar yet subtly strange. The rectangular windows are rotated into the building’s facade, resulting in two ruled surfaces at the top and bottom and transforming the window into an inverted trapezoidal bay. As the windows rotate in, the slabs appear to pull at the head and sill. This results in a facade that is both extremely blunt in its flatness and is also a dynamic bas-relief of smooth, undulating shadows. These windows also produced different interior moments as the shifting facade met the standardized unit layout. Views out from the interior became small events of forced oblique perspective as one looked both out and down the street at the same time, making each unit unique as it approached the enclosure."

Linking his design practice with his teaching, Young notes of the project: "In the fall of 2016, the third-year design studio at Cooper had the opportunity to travel to Mexico City. There we saw firsthand the incredible craft of concrete construction in Mexico, the boldness of an approach to architectural abstraction, and the subtle sophistication of curving ruled surfaces, such as those built by Felix Candela. With the DL1310 apartment building, we wanted to pay homage to these traditions while acknowledging contemporary digital design methods."

Linking his design practice with his teaching, Young notes of the project: "In the fall of 2016, the third-year design studio at Cooper had the opportunity to travel to Mexico City. There we saw firsthand the incredible craft of concrete construction in Mexico, the boldness of an approach to architectural abstraction, and the subtle sophistication of curving ruled surfaces, such as those built by Felix Candela. With the DL1310 apartment building, we wanted to pay homage to these traditions while acknowledging contemporary digital design methods."

The DL1310 Apartments project also received a P/A Award and was featured in Metropolis Magazine and ICON.

Photographs by Raphael Gamo.

Tags: Michael Young

A Manifesto and Call to Action to Build a Cooper Union Free of Racial and Social Injustice

POSTED ON: August 31, 2020

SUBMITTED BY THE ANTI-RACISM TASK FORCE OF THE IRWIN S. CHANIN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

As Architects, we hold a precious and critical space for how social imaginaries evolve, are reflected and contested. This delicate space ideally seeks to balance the poetic and the pragmatic, intangible virtues and tangible deliverables of “dwelling,” and requires an ongoing dialogue with society and the multiplicities and particular roles of architecture. We are collectively seized with the matter of contributing toward true social justice, through the vehicle of architecture, architectural thought, empathy and a profound belief in the power of creativity to unlock and lubricate the stymied wheels of social progress.

As architects we are not the sole arbiters of the built environment, but we are complicit in the perpetuation of the structural injustices when we give credence and expressive agency to power configurations that exist at the expense of others and when we are uncritical of the injustices which allow certain architectures to thrive in the real or imagined world.

The Black Lives Matter movement and its associated articulations are not a new cry for social justice; they are one of many waves of struggle, extending back centuries, but it is our wave, it is our struggle. The baton is firmly in our hands. Racism is a wicked problem, interwoven with capital, political structures and the very founding material of the Republic. As much as democracy is not an event, but a lived practice of diligence, oversight and rigor, so too must our fight against Racism be, in all its deceptive and surreptitious forms, and in so doing we may build a new edifice on the ashes of the old.

We seek a world beyond the narrow confines of racism, but one which celebrates our diversity as critical ingredients for the social imaginary of a progressive world. We are anti-racist, but unashamedly and even more so, pro-humanist—but to achieve that we must measure, frame and understand the ways in which racism conceals itself through our pedagogy, our canon, what we celebrate as virtuous and what we condemn.

We embrace the unfamiliar path that lies ahead. Our struggle is as much institutional as it is personal. We are modest about our capability to change the world, but we are bold enough to assert our right to attempt to do so. We are cautious about our certainty in this moment, but we are determined to discover a better way of being. This is why we are architects.

Context: In July 2020, students, faculty and alumni of the School of Architecture of The Cooper Union formed an ad hoc task force to propose positive actions to dismantle structures of racism and injustice in our institution. We were inspired by the “Collective Student Letter on Fostering an Actively Anti-Racist Institution” and the Zoom Town Hall following the collective grief and outrage over the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests. Taking into consideration the distinct authority and spheres of influence of four tiers of institutional power at The Cooper Union, this Task Force presents a Framework for Partnership and action items at each of those levels: 1. Individuals and Small Groups; 2. Formal Committees and other Institutional Entities; 3. Deans; and 4. The Administration and Board of Trustees.

To view the full document—A Manifesto and Call to Action to Build a Cooper Union Free of Racial and Social Injustice—please click here.