Archlog

Jeffrey Brown — A Force for Architectural Inspiration

POSTED ON: February 27, 2024

The Glider, from the 2012 exhibition Massimo Scolari: The Representation of Architecture, 1967 – 2012. Presented with generous support from Elise Jaffe + Jeffrey Brown.

The School of Architecture mourns the loss of our dear friend Jeffrey Brown, a man who never tired of being a student, finding joy and true excitement in listening deeply to architects, artists, and thinkers speak about their work, their discipline, their intentions, and motivations. He and Elise Jaffe, his wife and constant companion, valued and encouraged and generously supported the work of learning and teaching in all its forms at many institutions: public lectures, exhibitions, installations, catalogs, books, and films. Our school has been the beneficiary of their generosity and their friendship since 2004; for many years they directed their contributions to the Dean’s Circle discretionary fund—a measure of their trust in the School and their warm regard for our deans. One year, with Elise and Jeffrey’s support, the School installed a scaled reconstruction of Massimo Scolari’s 1991 Glider on the roof of the Foundation Building portico as part of an exhibition of Scolari’s drawings and models in Houghton Gallery. Perched on the outside of the historic structure as if ready for flight, the wings, which remained on the portico long after the run of the exhibition, reminded all who entered the building of the power, beauty, and mystery of architecture and art during a time of deep financial turmoil at the school.

In 2022, Elise and Jeffrey fully endowed the School of Architecture’s Student Lecture Series, which is curated and hosted by a small committee of students. Jeffrey was especially interested in learning from the students at Cooper, wanting to know whose work challenged them or inspired them, what work was important to deepening their understanding of architecture’s role at this time, and how they imagined an architecture of their future. Elise and Jeffrey attended many of the lectures; they took pleasure in the intensity of the students’ questions and would often join the students following the event for informal conversation with the speaker over a shared meal. Their interest in the students’ point of view was a measure of their own commitment not just to architecture, but to the education of architects, to the future of architecture, and to the School’s community.

We will forever miss Jeffrey’s belief in the importance of architecture, and we mourn the loss of his quiet presence, his warmth and kindness, and the joy that he shared with Elise.

Elizabeth O’Donnell

Distinguished Professor Adjunct

__________________________

To the unknowing eye, Elise and Jeffrey might have appeared as curious bystanders or parents: seemingly anonymous audience members on reviews and in lectures. In fact, they have been anything but! And that has been a secret of their inconspicuous and longstanding presence within the discipline of architecture. They have served as guardian angels for a field in consistent need of support, encouragement, and infrastructure. Inspired by an endless and insatiable enthusiasm for architecture as a discourse, these two travelers have been seen commuting between many schools of architecture, including Cooper Union, strategically supporting experiments, explorations, and events over decades. Their uncanny anonymity has been their main arsenal, but their generosity eventually propelled them to an inescapable presence. Still, it has been their unswerving passion for granular intellectual developments that led them to participate in every significant evolution of the field.

Jeffrey Brown’s untimely passing has left us with a deep void—he and Elise have become our family, cheering us on as they would their own offspring, with endless support. It is no accident that my deanship at Cooper Union was so easy: it was with Elise and Jeffrey’s support that we navigated the financial crisis some eight years ago. But in the process of giving, they offered a friendship more enduring than any individual or institution could ask for. I think I speak for everyone at Cooper Union when I offer these words of condolence to Elise. You and Jeffrey have been and will remain an essential part of our community.

Nader Tehrani

Professor

__________________________

With the passing of Jeffrey Brown, the School of Architecture has lost a beloved member of our community, but his profound legacy of support and generosity remains. Over the years, Jeffrey’s steadfast commitment to the learning and teaching of architecture has enriched the lives of countless students and faculty members. Always alongside his wife, Elise, Jeffrey tirelessly championed the importance of architecture, contributing to the growth and development of every facet of the discipline through patronage and encouragement. During my time as acting dean, Elise and Jeffrey have displayed incredible generosity, most notably in supporting our Student Lecture Series, which they actively engaged with enthusiasm. Jeffrey’s gentle demeanor and warmth will be deeply missed. Yet, his lasting impact on our Cooper community will serve as a tribute to his kind, unwavering spirit and his dedication to architecture.

Hayley Eber

Acting Dean

Remembering Tony Candido

POSTED ON: November 3, 2023

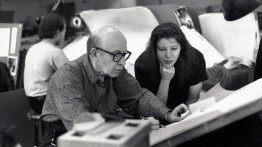

Anthony Candido at a desk crit with Aimee Bida, a third-year architecture student, Spring 1992.*

Tony Candido’s colleagues, friends, and former students reflect on his singular trajectory within the disciplines of art and architecture and the immeasurable wisdom and guidance he imparted on those he encountered throughout his life.

Toshiko Mori—I was very lucky to have had an opportunity to teach with Tony. He was an honest and clear critic who had the capacity to see into the true state of students’ thoughts. He had an uncanny ability to observe and bring about the essence of everything. The morning of the day he died, I happened to bring out a painting of his that he had given me. I noted that there were no false notes and every stroke was in the right place, balancing each other, black and white. Tony must have been trying to tell me something: that he was crossing over, but do not forget.

I have fond memories of traveling with Tony and his wife Nancy to Asahikawa, Japan in the eighties. Nancy presented a dance performance and Tony gave a calligraphic painting demonstration. As he always did with Nancy’s performances, he designed the stage set and costumes. I remember many fantastic performances of their collaborative work at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. I was in Asahikawa again this past June and Tony’s calligraphy is still prominently displayed in the lobby of the biggest and most sustainable furniture company in Hokkaido. It was a lot of fun traveling with Tony in Japan because I think he has the soul of a Japanese sage.

Tony was one of four young architects that IM Pei invited to New York when he started his office. The others were John Hejduk, Harry Cobb, and Ulrich Franzen. Later he joined Davis Brody and worked on US Pavilion for Expo ’70, which had the most innovative membrane roof and became the genesis for the largest manufacturer of membrane structures in the world. Tony always directed us with his wisdom, and whomever he touched aspired to achieve greatness. I often ask myself "what would Tony say?" and remember his sobering, uncompromising vision and his wonderful smile. I will miss him greatly.

David Gersten—

There's so much in one's mind, so much in that repository. It all goes into the hopper, and the hopper is endless, bottomless. Sometimes, when I'm working, these images pop up. I may not realize it at first, but they're there. —Tony Candido

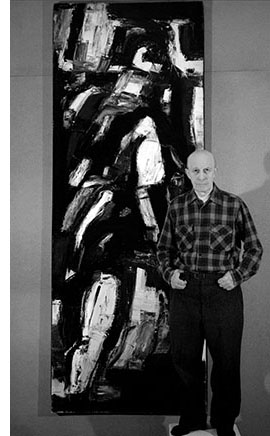

This short fragment offers a glimpse of Tony Candido’s depth and directness. Tony was many things: a painter, an architect, a searcher from The Bronx… He was a fighter pilot in World War II who then studied architecture with Mies van der Rohe in Chicago, and went on to be a magnificent teacher for decades in The Cooper Union’s School of Architecture, where I had the great honor of being his student and his teaching colleague. Tony was a rigorous pragmatist, especially when it came to mining the depths of the spirit. He was endlessly curious about the ineffable workings of the soul as they played out in substance and space—see his Night Paintings.

Tony and John Hejduk met working at IM Pei’s office in the mid-1950s, when they were both in their late twenties. Soon after, Tony began teaching architecture at The Cooper Union and, in fact, Tony was the person who went to Esmond Shaw, then assistant dean of the School of Art and Architecture, and told him he had to meet this guy named John Hejduk. As John said of Tony, “Real knows real, and there’s not a bumble bee around that could get that guy to drop his bone of conscience.”

Tony Candido’s direct depth was no swimming pool, it was an ocean 100 years deep—

his ‘Great White Whale is Black’—and all of us are better people for his friendship, work, and teaching.

Sue Ferguson Gussow—Anthony Candido, a man of depth, complexity, contradiction. A bomber pilot. A devout Buddhist. A man of many words—or very few. Eloquent and blunt. “You should meet Tony Candido,” Bob Slutzky said to me. “He’s an interesting painter.” Interesting he was, indeed. On my first studio visit, he was painting a series of nude crouching men. Himself. The colors were dark, moody, boldly brushed. What difficult postures to assume, I thought. Not possible to keep for long. How could he paint them, crouched like that? Of course, these were paintings of the mind as well as observation. Marks made from observation and memory both, quickly and raw, with authority.

Reminiscing about him recently, Beth Sigler AR’94 said, “… I adored Tony Candido.” Timing a live model’s pose, he had cautioned her, “You have two more minutes to ruin that!” “I learned to step back, to regard my work, to consider what I was doing…” she recalled. He would stop by her desk, ready to engage with whatever she might be doing—discussing a piece of paper from her papermaking class, for instance. She felt his support, his kindness.

I often went to performances staged by the dancer and choreographer Nancy Meehan, Tony’s beloved wife. They were also performances of Tony’s art. They were his bold brush work in motion. The calligraphic marks on the company’s costumes, designed and painted by Tony himself, were danced in space to Nancy’s choreography and Eleanor Hovda’s music. Tony’s collaborative costume art was Action Painting in its truest sense. However, unlike Action Painting’s credo of non-representation, Tony’s paintings held narratives. He had much to say. He told it as he saw it. He told it like it was.

Kyna Leski—Anthony Candido was my first studio professor at The Cooper Union. The projects he gave shaped my understanding of architecture and pedagogy. I remember being at my desk and suddenly realizing that he was standing next to me as I worked. His presence disappeared into saying what was necessary to induce contemplative practice.

It started like this: “2 posts (8” x 8” square; 12’ long). Span them. Brace them.”

At first, I contemplated (and tackled) a structural problem. Then I contemplated a construction problem. I contemplated form. When one spans and braces two posts, there is a portal: a here and a there and a through. That was when I understood, for the first time, what architecture is. I’ve returned to that moment throughout my education and my career, carrying forth these lessons.

Stephen Rustow—Tony Candido was more or less responsible for my teaching career at Cooper.

In the spring of 2003, I was among a group of invited jurors to the Third Year final review. We were in the lobby, arrayed in front of the long wall densely hung with drawings, and Tony was in the last seat on the right, saying nothing, but concentrating intently on the commentary. About halfway through the afternoon, just before a break, he suddenly turned towards me and said, “Hey you, kid—you teaching somewhere?” It took a moment to realize the question was addressed to me—it had been a long while since anyone had called me ‘kid’—and I answered no, I was practicing full time. “You wanna teach here?” he continued; I mumbled something about what a privilege that would be, still not sure if I was being led on. “I’ll talk to the Dean” he concluded. Three months later I got a message from Tony Vidler saying I should give him a call.

In the two decades of teaching that began that fall, I taught with Tony four or five times, often in Third Year, which I had been asked to coordinate and revamp to integrate questions of structure, materials, and methods using a typological approach to tie together analysis in the fall and design in the spring. Tony was a splendid colleague and even though he had taught that very course on and off for over thirty years, he was invariably encouraging, and very exacting, in our attempts to give it a new focus.

We occasionally did desk crits together and I quickly learned that he called lots of people ‘kid’—an age difference of ten years seemed to be the cut-off, which cast Tony himself in the role of the wise elder, one he played with great relish. He was a deeply perceptive critic, who expressed observations of great subtlety with an unerring directness. Indeed, Tony had a kind of plain-spoken gruffness that could intimidate students and colleagues alike, until gradually one came to understand it as a kind of performance that hid a shyness and fundamental sweetness he chose, for whatever reasons, not to show directly. He was also mildly hard of hearing, an affliction the severity of which seemed to vary in direct proportion to what he actually thought of whatever you had just said. If Tony repeated twice, “I didn’t get what you just said,” it was a sure sign that you might want to rethink your comment or reframe your question, or refrain from asking it at all.

Wonderfully opinionated yet perennially open to new ideas, tough in his expectations but invariably encouraging of younger colleagues and students alike, and sweeter than he would have liked any of us to know, Tony carried his contradictions with grace and great charm. The school had already felt his absence these last years; we won’t see his like again.

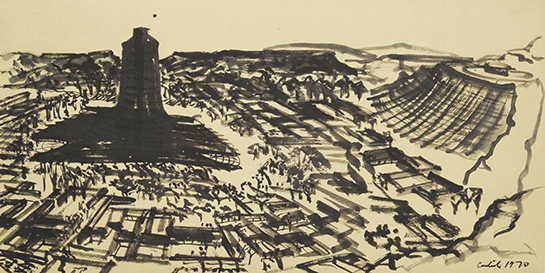

Mersiha Veledar—I am deeply saddened by the loss of Tony Candido, a former professor, colleague, inspiring mentor, and friend. Tony instilled excellence and love for architecture and the built environment. His distinct New York tone reverberated throughout the studio walls upon his entry, as he led us to develop exquisitely detailed plans and sections for new urban farms and housing projects in Germany (an area he admittedly bombed while serving as a pilot in the 1940s), for the third year Building Integrated Studios he taught for decades at The Cooper Union.

Tony’s commitment to advancing the work of his students was matched by his bold humor. In our very first encounter in 2000, he jokingly shared an anecdote from his visit to an ear doctor earlier that day, “I was supposed to get two hearing aids this morning, Mersiha, but I only got one so I could still yell at you!”

As the initial impact of meeting him settled, I found that behind his unstifled honesty there was humbling richness, having led an extraordinary multifaceted life as a brilliant educator, a practicing architect, a World War II pilot, a painter, and a surreal modern dance costume designer. The thick ink brushstrokes in his monolithic paintings paralleled the ethereal movement of dancers through the air—a study that arose from the deep love for the work of his late wife Nancy, who I had the privilege of knowing during the years of our friendship. Tony will be sorely missed and dearly remembered.

Kevin Bone—I met Anthony Candido in 1985. I had just joined the faculty at Cooper Union. Candido was part of the era’s incredible assemblage of educators: architects, artists, poets, and scholars from all walks of life, joined in one of the great experiments in architectural education.

Candido and his frequent teaching colleague, Richard Henderson, taught the analysis program. Analysis was an anchor studio where seminal works of architecture, from all ages and all places, were examined with fresh eyes. The student analyses of these works were themselves inspired artistic accomplishments. Students didn’t replicate a known understanding of architectural works. Under Candido’s guidance, they found their way to a personal understanding of the architecture. This was very much an artist’s approach to scholarship. Candido was a master of the process of acquiring knowledge through experiencing the accidental because that's how he painted. He would paint, look, respond, move on; his goal was not imagistic—it was to be alert to possibility.

I had the privilege of joining the Henderson and Candido studio in the 1990s. Every day was a chance to engage with this special world. By the late 1990s, Tony and I had partnered in various design studios. Starting in 1999 we did a series of studios called the Urban Farm. I loved this problem, and many people assumed it was something I had pushed for, but it was initially Candido's idea. Tony's early architectural speculations often imagined megastructures engaging the landscape, where boundaries between building and natural features blurred. I remember well a student who had proposed a wonderful landscape of apple orchards along the Newtown Creek. It was while overseeing this project that we learned there was such a thing as the Newtown Pippin. We all acquired this knowledge through experiencing the accidental.

The last twenty years or so, after many, many years of working together, Tony and I became good friends. He also developed a wonderful relationship with my wife, Eugenia. I’m going to let her say a few words here.

You know how we choose families in life? Well Tony was my chosen Dad. I went to him for advice, usually wielding goodies from the Italian delis on Arthur Avenue in The Bronx where he was born. On one of my book tours, I was having a hard time feeling comfortable with my presentation, and I was experiencing a lot of self-doubt. I asked Tony “How do you handle self-doubt when you are at the lectern?” And he said “Gena, you just talk about what you know from your own experience. Nothing else matters. Then you’ll have no problem.” I have replayed that conversation, the cafe where we were, and how friggin’ hard it was to maneuver him into the booth, every single time I have spoken in public since.

Tony, and his wife Nancy Meehan, came over for dinners that were always filled with stories; decades worth of stories. At his 90th birthday he told us of the bombing raids on Dresden. Candido was in the Eighth Air Force, a mere boy of eighteen when he embarked on the most terrible of human undertakings: the conduct of war. He told the story with typically Candido levelness. It was what it was, he was doing what he was called upon to do, and he tried to learn from it all.

Every accidental experience, a chance for learning.

Tamar Zinguer—Being Professor Candido’s student felt like being on his team. He would call you by your last name, root for you from the sidelines, and, like a demanding coach offer “tough love.” A bit too tough, I told Tony years later, once we became colleagues. He didn’t believe me at first, but after checking with his wife Nancy, who concurred, he offered apologies. “No need!” I said. We all learned from him to be exacting in our arguments and drawings—no fashion or jargon allowed—while being as expressive as possible with any mark intimating space on paper. These were invaluable gifts. Thank you, Tony Candido, for your candor and friendship.

Anthony Titus—On a Sunday afternoon in May of 2006 while walking along the Fifth Avenue side of Central Park, my attention was captured by what appeared to be a long line of people stemming from the entrance of The Frick Collection. As I crossed the street to inquire about the purpose of the line, I discovered that a Francisco Goya exhibition was in its final hours. Recognizing the low likelihood of getting tickets at the last minute, I quickly brainstormed and proceeded to purchase the least expensive membership that would allow me and a guest access, without having to wait the long line. Immediately upon making the purchase, I called Tony and alerted him to the urgency of the situation, at which point he responded, “Give me five minutes and I’ll call you back.” Five minutes later my phone rang, and I was greeted on the other end with “I’ll hop in a taxi and see you there in 45 minutes.”

After his taxi arrived, we entered through the 70th street entrance and calmly made our way towards the exhibition. The show, titled Goya’s Last Works, was a beautiful cross section through some late career masterpieces by the artist. Prints, drawings, and paintings adorned the walls of the galleries, most of the works well known, some slightly more obscure, yet all captured the human condition in a way that seems to happen only once every few centuries. As Tony and I moved through many rooms, eventually nearing the end of the exhibition, we encountered a small wooden glass case which contained a half dozen miniature works of which were unfamiliar to us both. No bigger than postage stamps, these sensitive paintings made of black carbon and watercolor on ivory tablets depicted figures and heads which managed to capture the emotional depth of Goya’s large-scale black paintings which reside at the Prado Museum.

Painted between 1824 – 1825 as Goya neared his 80th birthday, these works seemed especially impressive due to the fact that his hearing and eyesight were all but gone by that stage in his life. As we turned away from the glass cases to exit the room, Tony turned to me and remarked: “Well kid, I’m glad I got to see this; it was certainly worth the ride up here. Seeing these small works is proof that seeing is not simply about the eyes—it’s in the mind and perhaps in other places that we’re probably not yet aware of.” As we exited the museum I was struck by Tony’s unique walk. There was a beauty in the way he would slowly and steadily put one foot in front of the other, as if he was confidently moving towards a future that may have only been fully visible to him.

The quintessential thinker-maker—in fact, there was no separation between these two acts for Tony Candido. His discipline and dedication to the arts of teaching, painting, and architecture remained at the core of his being and lasted to the very end of his life. At the age of 99, lucid in thought, memory, and intention, he worked as much as humanly possible, often spending long hours on concentrated sessions of drawing in small pads, using soft dark sticks of graphite. Over the last year of Tony’s life, I had the honor and pleasure of sharing several memorable calm and reflective conversations. Visiting him in hospital, and later in his home, he allowed me to look through the numerous drawings pads which he had been fastidiously working on over the course of his recovery. Meticulously constructed with layers of delicate graphite marks, the drawings captured the dense atmosphere of water and light that he and his beloved wife, dancer and choreographer Nancy Meehan, would experience on their many trips to Point Lobos and Big Sur in the early 1970s. On one recent Sunday afternoon visit as I carefully turned the pages of one of his many drawing pads, Tony explained that the fog and mist would sometime become so dense that they would be forced to stop the car, at which point Nancy would hop upon the hood (her feet resting on the bumper) while holding a flashlight to illuminate the nearly invisible road ahead. As Nancy would navigate, Tony would inch forward a few miles an hour until the fog would clear or their destination had been reached.

These late small delicate works on paper echo both the solidity of his Night Paintings of the late 1950s or the fluid line work of his monumental ink Heads of the late 1980s. To say that Anthony Candido will be missed is indeed a vast understatement. Tony’s presence loomed large in the lives of his many students and colleagues that he encountered over the six-decade span of his career as an educator. I feel a deep and profound sense of fortune to have been his student as well as having sustained a three-decade long friendship with him. Over that span of time Tony would generously share many memories, stories, and thoughts on the nature of life and art. A most sensitive and astute reader of poetry, literature, and philosophy, he had an ability to penetrate layers of complexity and arrive precisely at the core of a question. His love and knowledge of the writings of as Miguel De Unamuno and Paul Valéry as well as his passion for the music of Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, and Lester ‘Pres’ Young (his favorite) are evident in the soulful depth of his drawings, paintings, and visionary architectural projects. I am fortunate to have known Tony as a teacher, mentor, and beloved friend. His humane spirit and principled mind will continue to reverberate in the lives of the many people he touched over his long and illustrious life.

*Photo credits: Photographer unknown, Anita Kan, Johan Elbers, Gina Pollara, Barb Choit, Liselot van der Heijden, Photographer unknown

School of Architecture Faculty Remember Tony Vidler

POSTED ON: October 27, 2023

Tony Vidler with colleagues and students at a 2019 School of Arhitecture celebration.

As The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture mourns the passing of Anthony Vidler, colleagues and friends at The Cooper Union share their remembrances of him, his profound impact on the discipline and history of architecture, and his decades-long role as a transformative educator.

Nader Tehrani—Tony’s presence is synonymous with architecture itself: his writing in Oppositions forming a critical foundation for an entire generation, his research transforming our reading of the Enlightenment, and his subsequent books, such as The Architectural Uncanny, revealing a protean capacity to speak across ages and architectural debates. His insatiable curiosity never ceased and continued through his scholarship to his last moments. Mine is a tribute to the person behind that scholarship—a ‘former dean’ of formidable warmth, a person who expanded the meaning of a true ally. Possibly more comfortable as the éminence grise, Tony offered his wisdom with delicate generosity, imposing himself only gently, knowing when to recede to allow a new generation to emerge. He was infinitely forgiving, allowing mistakes without rash judgment. A disciplined parliamentarian, he helped rebuild our governance through robust debate, embracing discourse as a collective enterprise. A gracious diplomat, his intellect served as his best guide, knowing that humor was often the best weapon when gravity did not suffice. In an era thoroughly lacking in decorum, Tony gave us a sense of history and perspective. And when all else failed, he was always there for a scotch, humbly acknowledging that not all problems had a solution. Architecture has lost a great friend and ally; I know I speak for all of us when I say that I will miss Tony immensely!

Samuel Anderson—I first met Tony Vidler in the fall of 1976, when he was a teaching and research Fellow at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, and I was a neophyte intern. It was an inspiring and lively but intimidating place, where people took themselves very seriously. Despite his towering intellect, knowledge, and fluency, Tony conveyed no pretenses. On the contrary, he was warm, sincere, and full of wit. What a wonderful man to have known for all these years.

Diana Agrest—Writing about Tony in the past tense is an emotional challenge, and I write these words with a heavy heart. He was not just a friend; he was a unique and enduring presence in my life, where our personal and intellectual dimensions were in sync over the years. Tony has been a true and significant friend, ever since our paths crossed at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York, where we both became Fellows, engaging in an active part of what was to be a defining moment in architecture's critical path.

I met Tony as I was engaged in the criticism of the ideology of urban planning models, while Tony was visiting from Princeton, where he taught. We were strangers to each other, but our connection was immediate. It was Tony's perspicacious and provocative wit that was evident from the moment we met, and from there, our enduring friendship and intellectual camaraderie was born.

While a Fellow at the IAUS, following an open call, I received a full-time appointment at Princeton's School of Architecture. Our approaches to architectural discourse differed, as I delved into the capitalist implications of architectural ideology influenced by French Structuralism, Post-structuralism, and political philosophy, while Tony was rooted in a British school of thought. It was a divergence that led to many passionate and greatly productive discussions at Princeton.

In 1973, when the IAUS Oppositions journal was founded by Eisenman, Frampton, and Gandelsonas, we were both contributors in its first issue, Oppositons 1. This connection between Princeton and the IAUS, and our intellectual worlds, was instrumental in developing new frontiers for a critical thinking of architecture.

Tony's involvement in Oppositions grew as he guest edited the memorable issue on the Beaux Arts, in a way an indictment of the more complacent approach of MoMA's Beaux Arts exhibition that opened at the time. After that, Tony became an editor of Oppositions and a Fellow at the IAUS, so our paths intertwined in our parallel work—Tony was working as a historian, as I worked on architecture practice and theory while we both taught in the education programs there, partaking in all the Institute's celebrations, exhibitions, and exchanges with other Fellows and the New York architectural community.

Tony's gift for writing, coupled with his prodigious memory and boundless curiosity, were extraordinary. He approached every subject with depth in research and a unique perspective. Tony was a historian with an architect's heart and eyes, adept at articulating the complexities of the formal and sociopolitical aspects of architecture, from his work on the French Enlightenment, such as his landmark book on Claude Nicolas Ledoux, to his fascinating essay on the architecture of the Lodges, the Beaux Arts, and through to Modernism.

An inquisitive mind and creative spirit permeated all of Tony's work, spanning history, contemporary architectural questions, and touching on art, literature, politics, and film. It was in this transdisciplinary approach that we found common ground. On a personal note, I was privileged when he insisted on writing the introductory essay for Agrest and Gandelsonas Works.

Our paths crossed once more at The Cooper Union, where I had been teaching for many years after leaving Princeton, as Tony assumed the role of Dean. It was a challenging and monumental undertaking with regard to the significance of John Hejduk's legacy, but Tony approached it with a certain modesty, despite his standing in the field. Tony not only upheld this legacy but, focusing equally on the discipline as on the discourse of architecture, he sowed the seeds that brought the school to the great place it is today, with Nader Tehrani following as Dean.

As Dean, Tony championed academic freedom, among other things carrying on the tradition where faculty curated their own end-of-year shows. He also opened the "sanctum" of the Dean's office to the entire faculty and staff, bringing a sampling of his gourmet expertise to this event, therefore fostering collegiality and camaraderie in our shared commitment to teaching and the school, an event that we eagerly anticipate to this day.

Among his many contributions as Dean, Tony's creation of the graduate program stands out. I had the privilege of working with him in the context of the Curriculum Committee to shape the program's scope, concept, and direction. He entrusted me with the Advanced Design Studio, where he implicitly allowed complete freedom to propose and develop pedagogical approaches, such as the Architecture of Nature / Nature of Architecture studio, which he steadfastly supported.

Tony was a giant in the history of architecture, an intellectual with boundless curiosity, creative energy, a great sense of humor, and an exceptional histrionic talent manifested in his captivating lectures and seminars. But beyond his professional achievements, Tony was a cherished personal friend who shared in the joys of life.

His voice and generous spirit will be sorely missed, leaving a profound void in our world and our hearts. However, this void will be filled with the enduring legacy of an exceptional human being who touched countless lives as an intellectual, historian, teacher, and mentor.

Lydia Kallipoliti—Tony (Anthony) Vidler—my mentor, colleague, beloved friend, and inimitable force of life—shaped me and my life as an architect and a thinker. I owe him a debt that can never be repaid. But just as he shaped me, he shaped so many others. Most importantly, he shaped the field of architectural discourse and the world of ideas itself. He saw the future in historical evidence and the past in forecasts of the future. And yet, he maintained an unwavering optimism in life and in the power of architecture to influence livelihood. My loss, however gutting, is collective; a void that cannot be filled by another soul.

Tony was a living encyclopedia, and in our weekly dinners he persuaded me over the last years to write an

environmental encyclopedia, even though I resisted and conceived it as a giant act of chronic constipation. Tony felt this struggle in a visceral way and his partially British impulse to “carry on,” and produce an enormous body of work in his life, was coming from the understanding that parthenogenesis—the state of the mind generating pure ideas, unprecedented and unmixed with anything in the physical world—is a fallen myth. Even Tony, whose sheer brilliance connected so many dots, relied on the ethic of work and the labor of writing that to him was a primordial need, a proof of life and an inevitability. Another indelible mark on me was his teaching that the line between the past, present, and future is an illusion. As a historian and a voracious researcher, whose mind was enlivened by curiosity, he saw the future within fragments of the past and the past within forecasts of the future. Learning from him and thinking with him, as a historian, I began to think of time as a mixture of past, future, and present stretched in spatiotemporal dimensions.

In his memory, I post here a short video of his talk at The Cooper Union in an event in 2016, where he pretended to be the sociologist John McHale, with a Scottish accent. This video evidences Tony’s spirit, humor, and boundless energy as a human and an educator, which was the other side of the immense body of work he left behind in his many books, texts, and exhibitions.

Elizabeth O’Donnell—When Tony came to The Cooper Union in 2001 as a professor and a dean, he had already made a significant mark on the discipline, having been a renowned scholar, writer, and teacher for over three decades. As an historian, Tony studied, analyzed, and interpreted the past, but as a teacher he lived and taught wholly in the present. His concerns were of and for the contemporary world, of history’s potential to help us understand our world and architecture’s capacity to contribute in a meaningful way to its future. He was an extraordinary teacher through his final days.

Tony and I worked together at the School of Architecture for twelve years; it was a remarkably vital time at the school. Tony engaged and empowered faculty and students alike to continue the school’s work of reimagining what a professional education in architecture might be. He was an intellectual force and an exceptional colleague, an eloquent spokesperson for the school and for the power of architecture. He invited new faculty to the school and supported continuing faculty to develop new courses, challenging all to evolve the curriculum, strengthening the school’s commitment to drawing and model making while fostering a parallel rigor in research, coursework, and advanced seminars. He encouraged critical investigations into the potentials for new computational and digital methods to serve as both analytic and synthetic tools. He insisted that students and faculty address the growing urgencies of the world through the lens and the action of making architecture: environmental degradation, the fragilities of cultures, civic instability, and the unacceptable consequences of extreme inequality. As teachers, researchers, and architects, we were continuously challenged to bring the work of studio and the work of the classroom closer together—design and history, design and theory, design and language.

Through it all we were inspired by Tony’s own prodigious creative work. Beautifully conceived books that are a pleasure to read, illuminating lectures, probing exhibitions. Tony was a giant in our discipline, and he was also our dear friend. A brilliant mind, a warm and generous heart, and a gracious host on innumerable occasions. Thank you, Tony. I am grateful for the time working and learning together with you. You will be sorely missed.

Guido Zuliani—Many will celebrate Tony’s indisputable scholarly achievements that through the years have shaped architectural debates and culture; many will celebrate Tony, especially here at Cooper, for the incredible, committed educator that he was. There will be time for all of this and for recognizing his tremendous legacy that survives in the work of his many students and colleagues. Right now, instead, I cannot but remember and celebrate Tony as a wonderfully generous colleague and friend with whom I have shared an office for about a decade, and who I already deeply miss.

During the time we spent working together, sometimes the occasional reappearance of a particular book from behind the many that covered most of the walls of our shared space, or the emergence of an old handwritten document from the papers that filled the boxes surrounding his chair, or simply an old slide, become for Tony the occasion, if not an invitation, to narrate a segment or a particular moment of his life—and through that, with a few words, the chance to illuminate the nature of a particular historical moment, its events, its protagonists, its social and cultural pathos. A rare gift from an individual who lived his life with great commitments, participation, and empathy.

Tony never held back in sharing his experiences and thoughts, and his advice and critiques as well. Our lunches consumed sitting at our desks, were the occasions for me to listen to, and to discuss, among other things, his thoughts about the dire state of our world today and his constant preoccupation, and sometimes indignation, for the responsibilities of our discipline. But he never lost his generous, energetic optimism. This tension constantly animated his work with his students: for Tony the practice of teaching had to project, to embody, as generously as possible, such preoccupations, and among the many things that I received from him is the fundamental understanding that to operate, as he had always tried to do as an educator, is above all, and in the most profound way, a civic act.

Thank you, Tony for everything you’ve given me, and everybody else you encountered. I miss you a lot, already. Goodbye, my friend.

Bridging the Megacity: Cooper at the Seoul Biennale

POSTED ON: September 8, 2023

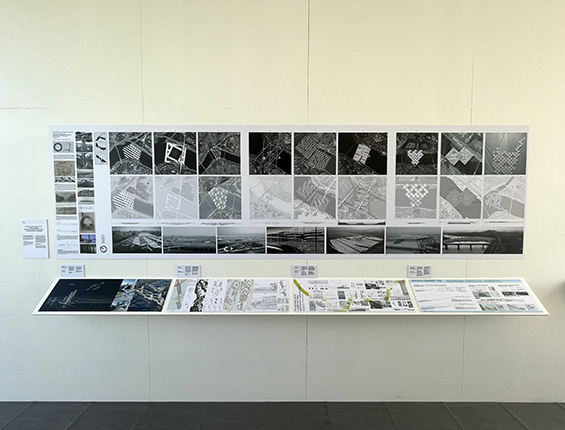

One of three site models produced by Nima Javidi's Design IV studio, spring 2023. Photo by Katie Park.

The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture is thrilled to announce its participation in the 4th Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism in Seoul, South Korea. Work by twelve current thesis students from their spring 2023 Design IV studio section with Associate Professor Adjunct Nima Javidi is now on view from September 1 – October 31 in the Biennale’s Global Studios exhibition. The students who participated in the studio and whose work is being exhibited are Jihoo Ahn, Razaq Alabdulmughni, Jaemin Baek, Laela Baker, Aerin Chavez, Ji Yong Chung, Martina Duque Gonzalez, Alex Han, Annie He, Jiwon Heo, Rebecca John, and Xinyuan Zhang.

Hybrid Mats

At the invitation of Leif Høgfeldt Hansen, curator of the Global Studios section, Professor Nader Tehrani encouraged Javidi to organize his studio around the exhibition’s theme “Bridging the Megacity,” a prompt to consider bridge designs for three sites along the Han River bisecting Seoul. Thirty colleges and universities worldwide submitted sixty-five designs for projects sited near Noeul Park, Nodeul Island, and Seoul Forest. The Cooper Union was one of a dozen participating schools invited to exhibit its student submissions in detail.

Javidi’s studio used the Biennale’s prompt to investigate a new paradigm for bridge design. Moving away from the entangled relationship between structure and path configurations common in bridge design, this paradigm explored a fine-grain montage between patterns of ecology (waterways, windways…), structure (rhythm of columns, arches, shells…), and human settlement to create a thick, light, newly constructed, layered ground over the Han River.

Using Seoul and its unique geological condition as a starting point, the studio considered multilayered mat structures that can accommodate, through their thickness and crust, the passage and continuity of waterways, windways, and human inhabitation. This reading of infrastructure, because it operates at both human and ecological scales, informed design approaches that afford ecological continuities while allowing human settlement as an overlay. The resulting mat generated from different rhythms of structure, access, and ecological flow required reworking and montage with the edges of the bridge to create a seamless and meaningful connection with urbanity on each side of the river.

As a whole, “Bridging the Megacity” addresses the complex web of challenges that define the modern megacity of tomorrow, and its projects evoke unity and a bridge between cultures, ideas, and aspirations, transcending geographical borders to contribute to a global dialogue on sustainability and urban resilience. The bridges are not just physical connections over the Han River; they embody the multifaceted solutions that our cities demand for the future. In this era of unprecedented urbanization, cities worldwide grapple with a pressing need for collective spaces that foster interaction and community engagement. These bridges exemplify the fusion of design and purpose, offering platforms for ‘soft traffic,’ social convergence, artistic expression, and cultural exchange. They are not just functional conduits; they are vibrant arenas—addressing issues from biodiversity and water management to urban farming and air quality—that catalyze connections and invigorate the social fabric of the megacity.

Seoul Biennale

The Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism was first launched in 2017 to address urban and architecture-related challenges resulting from rapid urban growth in one of the world’s most densely populated cities. Since its inauguration, the theme of urbanism and architecture has been pivotal in reinstating Seoul as a human-centered and eco-friendly city.

The Biennale aims to harness Seoul as a testbed as it explores and seeks solutions for urban issues in global cities. It is composed of five sections: a Thematic Exhibition featuring the key theme of each edition, a Cities Exhibition inviting leading public projects from around the world, an On-site Project which engages with Seoul’s most present issues, and Global Studios and Educational Programs, which establish discussions where the people of Seoul—global and domestic experts, public institutions, and citizens alike—can participate in drawing up a common future for the city.

The 4th Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism continues ongoing discussions from its past editions—Imminent Commons, Collective City, and Resilient City—with a focus on ‘Land Urbanism’ and ‘Seoul.’

Tags: Nima Javidi