MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE FALL 2021

GRADUATE RESEARCH DESIGN STUDIO II

Michael Young, Assistant Professor

Infrastructural Interruptions — 2021–2051

Increasingly, reality is defined through the exchange of data. The process of translating behavior and appearances through discrete abstractions is what counts and what is counted. Each of us, as individuals and as collectives, are inhabiting a public space owned by private interests that “know us” through the data trails we create. This should make us nervous. Privacy, identity, and agency are no longer defined solely within our shared physical spaces, but also by what we click on, type in, and look at. Multiple conflicting conversations revolve around who owns this data, how it is extracted, what it means when stored, filtered, and cross-referenced across large sets, and how patterns are then used to predict, manipulate, and alter societal behavior. An exchange of images is an exchange of information; it is political and aesthetic.

There are other issues to consider as well, ones that directly impact and are affected by the practices of architecture. Specifically, how reality is measured, modeled, disseminated, and speculated on through digital images. One way this has manifested across multiple practices, professions, and disciplines is through various scanning technologies modeling the environment as clouds of spatial points. Created from digital images, the result is a mediation of the world as captured between electromagnetic thresholds. These models are thus not simply three-dimensional dots of color, but include information regarding heat, reflectivity, materiality, moisture, and other luminous qualities. How this impacts the practice of architecture is an open question given that these models have yet to be fully engaged by the discipline.

Infrastructural intrusions within the city are tricky moments. The events where a highway, a bridge, or a tunnel leap over, dive under, or push through an urban fabric have long been sore spots in the city. They tend to be, at best, interruptions that are tolerated as necessary for the overall functioning of the larger system; at their worst, however, they are part of a long history of disruption disproportionately affecting neighborhoods along racial and class factors. Part of the trauma that these infrastructural ruptures create is due to what they disrupt and erase, but the other aspect is aesthetic. The tendency to treat infrastructure as a resolution of functional constraints and efficiency for a larger regional network ignores the cultural, ecological, and economic relations that each intrusion alters in the urban fabric.

There are twenty-one bridges and twenty-one tunnels in and out of Manhattan. Over the course of the semester, each student developed a design speculation focusing on one of these infrastructural interruptions as it alters its urban environment.

There were two initial prompts:

The first was for each student to create a point-cloud model of their specific “site.” This model was the basis for the design work of the semester. It was much more than a simple technical exercise—it was a political and aesthetic question regarding what changes when the environment is captured and modeled through energetic information.

The second prompt was temporal. The year is 2051. Each project is a documentation of what happened over the past thirty years of urban transformations after 2021. This temporal displacement shifted the design concerns from those of problem solving to speculation about how issues that we face today may play out in the built environment. Each project identified its own concerns to address and develop through multiple forms of media.

Projects

-

A Super Ramp-Gap System in 2051: A Playground Extended from Lincoln Tunnel

-

The Year 2051, Williamsburg Bridge, after the Great Flood

-

City in Shell – A Speculation of 2051 with Photogrammetry Techniques

Back

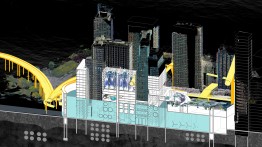

A Super Ramp-Gap System in 2051: A Playground Extended from Lincoln Tunnel

Xiyu Chen

The Lincoln Tunnel’s three tubes connect New York and New Jersey and provide ramps to the Port Authority Bus Terminal, carrying commuting buses and private cars. From 1916 to 1955, the Lincoln tunnel intruded upon and demolished the old grid-block system. Later, from 1955 to 2021 the grid-block system resisted the Lincoln Tunnel. The long-term conflict between the tunnel’s expanding infrastructure and the grid-block system created gaps—gaps between buildings, gaps across streets, and gaps occupying a whole block. These gaps replaced active urban fragments, becoming unwalkable areas.

The ramp-gap combination has since become a super system connected to the original grid-block system. It not only connects the tunnel’s three entrances and the bus terminal, but also weaves together different blocks, buildings, and layers. The new ramps I propose are layered on top of the existing streets and ramps, providing a variety of ramps layered vertically. This results in new vertical gaps that can be used as porous spaces for surrounding urban fragments.

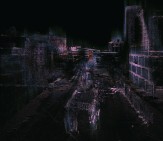

The Year 2051, Williamsburg Bridge, after the Great Flood

Geralis Foivos

The histories of the Williamsburg Bridge and its surrounding urban formations are entangled with the development of different architectural and infrastructural imaginaries, raising questions of urban esthetics since the 1890s, throughout the 20th century, into the first half of the 21st.

A significant moment in the history of the bridge, and a pivot for the development of this project, was the 1948 Jules Dassin’s film noir Naked City, one of the first American movies filmed outside on the streets instead of in a studio. New York City and particularly the Williamsburg Bridge become the spatial protagonists as the primary site of a prolonged chase that concludes the film. The numerous filmic street scenes of Dassin’s Naked City reconstruct a fragmentary vision of the city inspired by the crime photography collection of Weegee’s 1945 homonymous oeuvre, and became particularly influential for the psychogeographic maps of Guy Debord and the Situationists in the late 1950s. This fragmentary understanding of the urban fabric dependent on the differentiated experiences of wondering subjects associated with the history of this site is juxtaposed with the holistic ‘designed/planned’ visions for urban development. These two traditions of understanding the city—the holistic, top-down plans that fail partially in their implementation, and the fragmentary heterogeneous bottom-up reconstructions of the city from the experience of individuals—collide violently in this project, situated in the year 2051, which follows the movement of an agitated subject trying to return home after another big flood in the area surrounding the bridge.

Reconstructions of the city based on digital point clouds from aerial capture with LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technologies, in 2010 and 2017, are readily available as open data from the City of New York. This data, together with fragmentary scans of street scenes captured by the author using photogrammetry and LiDAR scans made with personal devices, are used to create a short film noir that follows the movement of an unidentified individual trying to return home when all of the surrounding neighborhood is underwater, during which the bridge and its speculative future reconstruction once again become the protagonist.

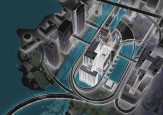

City in Shell – A Speculation of 2051 with Photogrammetry Techniques

Zifei Zheng

The Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel is located at the southernmost end of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Its entrance is surrounded by ventilated buildings and various high-rise skyscrapers in the city’s bustling financial district. Using photogrammetry, I scanned the tunnel’s entrance and surrounding environment and discovered that its ventilation building is unexpectedly unique—a windowless, monumental building, it operates in the service of people and the city. Using this unique ventilation building, I began to speculate about the Financial District in 2051.

In 2051, if sea level rise begins to flood Manhattan, the tunnel will be among the first structures flooded by seawater. If this ventilated building can’t process air air anymore, will it begin to serve other functions? Could the building become a tidal power plant? Ventilation equipment that previously consumed electricity could be replaced by a generator that produces electricity. To store water and ensure electricity production, a new dam wall system would be built around the tunnel, converting the block into a separate reservoir where high-rise buildings become new islands inside Manhattan, and their interiors also become cities inside reservoir system shells.