Thesis Year Snapshots: 2014

POSTED ON: May 29, 2014

This third and final article in the 2014 "senior snapshot" series focuses on the fifth-year students of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. As part of their final year of study, each must develop a thesis proposal they present to faculty and guests during a thesis critique prior to graduation. We sat down with three graduating students to talk about how they got to the school, what they focused on in their thesis, and how the time they spent at The Cooper Union changed them.

Tjhang Felicia Gambino, who goes by her last name rather than her first, credits the school of architecture with making her a different person. The seeds of that change can be found at the very beginning, when she was challenged by the famously intimidating home test required for admission to the school. A recent such test requested, among other things, a "self portrait in terms that have no reference to the body" and also instructed the applicant to "observe a structure such as a facade, a frame or an order. Draw an intersection."

Gambino, 26, was born in Jakarta, Indonesia and moved to Singapore during her high school years. After receiving a diploma in interior design there she wanted to get out of her "safety net" and study architecture in America at The Cooper Union. "In my first home test I depended on other people, like asking my teachers for their feedback, because I was not confident," Gambino says. "I was more doing the test by thinking, ‘What's the right answer?’ " She was not admitted to the school. So she got a job at an architecture firm in Singapore and applied again the next year. "The second time I applied I was like, 'You know what, if I don't get in, let it be just my fault.' So I was being truthful about the questions and showing the struggle.” Her change in thinking got her accepted to the program.

Five years later Gambino's thesis project, titled "Urban Transience," examines questions of living in a globalized age. She was inspired by Pico Ilyer's book The Global Soul and its notion of someone who feels no particular affiliation with any one nation. "I was really into that because I am one myself," she says. "I am a global soul." Unusually for a thesis proposal, Gambino’s has no specific site. "It is a structure that can be placed in any urban place in the world," she says. "I want to create a space for people who live a life of transience. When I move place to place, I struggle, even on an emotional level. So I am proposing transitional housing for such people."

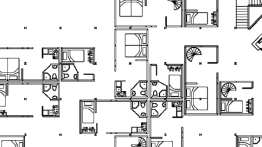

Gambino designed a 10' x 10' modular house that would travel with the migrant. She envisions the houses plugging into adaptable "connections" between them that allow for the fluctuations of such peripatetic populations. "The individual housing becomes the structure, forming a shape," she says. "And the negative area becomes a public space. The form is not the most important thing. It would change depending on the number of migrants. In New York, for example, it would be huge, but in Jakarta it would be small."

After graduating Gambino hopes to find a position at a firm in the U.S. that will sponsor her so she can get an architectural license. Failing that, she will move on, perhaps to Europe she says, and eventually make her way back to Jakarta.

Gambino says that she has changed since attending The Cooper Union. "It's the best thing to happen in my life," she says. "At Cooper Union you learn that the process is the most meaningful part. That's a huge change for me. The way my thesis is autobiographical is an example. It's like a kind of critical thinking. How do I transform something personal into a project? You start opening the mind.”

Jennifer Kim's story of attending the school of architecture exemplifies how each student makes the experience their own. Jennifer, 24, had settled in Queens, New York at age ten, after moving from Minnesota to Korea and then Colorado. A talent for fine art got her entry into New York City's exclusive Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. Later, she applied for early decision to The Cooper Union School of Art. But she did not get accepted. Undaunted and determined, she took a daring step into the unknown and applied to the school of architecture. "The first year was rough for me," she says. "I came into it not knowing anything about architecture, and I had a difficult time understanding what the professors were trying to teach us." But, she says, she found the structure of the curriculum to be supportive. It also allowed her to fold her fine arts background into her architectural work, something that became her hallmark.

Like Gambino, her classmate, Jennifer's thesis proposal touches on the notion of mobile housing. She decided to reconceive the notorious American trailer park. Her interest began when, taking a break from school after her fourth year, she joined AmeriCorps. "I worked at a trailer park in New Jersey immediately after Hurricane Sandy hit," she says. "The insulation under the homes was damaged from flooding. They had us come in and gut out the molding insulation and install new insulation by crawling under the mobile homes. It was a horrific experience but I am glad I did it. Sometimes you forget that there are places in need of assistance when you are in school for a long period of time.”

The work inspired her. "It struck me that mobile communities have a stigma attached to them, yet they take up so much of the United States," Jennifer says. “I thought it would be interesting to do a project on them." She started with what she saw under the trailers. "I noticed the residents used cinder blocks as the structure to hold up the mobile homes, but there could be a more stable and permanent solution. Also, these homes are called 'mobile,' yet they were immobile when the hurricane came. They couldn't just drive away."

She located her proposal in Orangeburg, South Carolina, a once thriving city now reduced to a strip mall "downtown" and a population of trailer parks on the outskirts of the city, according to Jennifer. "I thought there could be a way for a shrinking city to revitalize itself through a mobile community; reestablishing the mobile culture that the trailer used to allow while also reestablishing a city that was once functional. When trailers were first introduced, there was an established mobile culture. It wasn’t considered an impoverished way of living but an alternative lifestyle. I wanted to try and bring that thinking back and counteract their being considered a last resort." She reshaped the home, removing its superficial mimicry of a suburban house in such features as the pitched roof and boxy shape. Instead she imagines trailer homes made of lightweight materials that can be more easily hitched and moved. She also designed a permanent structure where the trailers could dock, which could add additional space.

Jennifer's thesis uses supporting materials that reflect her merged passions of fine art and architecture. Her model of the trailer and dock seems typical of an architectural proposal. But less typical is the life-size plaster casting of mobile home tire tracks she presents as "a message of the immobility with the possibility of mobility." She also integrates painting and watercolor into her final presentation. Still, she says she thinks of herself foremost as an architectural graduate. So much so that her next step will be to seek an architecture license after finding a job somewhere outside of New York. "I am a different person from who I was in first year," she says of her experience at the school. "I can actually talk about architecture and be passionate about it. And I can have my own opinions and fight for them. Even the way I present my work has changed. I have become more confident. It was rigorous. But I would do it again in a heartbeat."

In a previous snapshot we met a graduate who started out thinking he would pursue architecture but instead went into engineering. Harry Murzyn, 24, took the opposite path. Born in Taipei, Taiwan but raised in Indiana, he had a talent for math and science in high school and considered an engineering degree. But when he took industrial design and drafting classes, those skills met with an artistic talent as well. "I found I was really good at it and just kept going in that direction," he says. At the same time, during a class trip to New York, a tour bus guide turned everyone's attention to the Foundation Building. "The guide said, 'If you look out to your left, you will see one of the best schools here in the city. It's very selective,' " Harry recalls. Shortly thereafter he found The Cooper Union again while searching for architecture schools on the Internet.

In a previous snapshot we met a graduate who started out thinking he would pursue architecture but instead went into engineering. Harry Murzyn, 24, took the opposite path. Born in Taipei, Taiwan but raised in Indiana, he had a talent for math and science in high school and considered an engineering degree. But when he took industrial design and drafting classes, those skills met with an artistic talent as well. "I found I was really good at it and just kept going in that direction," he says. At the same time, during a class trip to New York, a tour bus guide turned everyone's attention to the Foundation Building. "The guide said, 'If you look out to your left, you will see one of the best schools here in the city. It's very selective,' " Harry recalls. Shortly thereafter he found The Cooper Union again while searching for architecture schools on the Internet.

Like Jennifer Kim (his girlfriend), Harry also took a year off after his fourth year and joined AmeriCorps. "Everything happens so fast, and I felt I wanted to take time to digest what I had learned," he says. Like Jennifer he came back with an idea for his fifth-year thesis. He had spent six weeks in Crown King, a former mining town turned recreational destination set amid ponderosa pines in the central Arizona mountains. Harry's days were spent on forest fire fuels reduction, clearing undergrowth and dead brush from town structures. "We would follow the fire department around as they cut up all this stuff with chainsaws, hauling it up and down the maintain to a wood chipper," he says. "They need to do this constantly. That's part of the reason that my thesis project turned toward the more sustainable questions of such an endeavor."

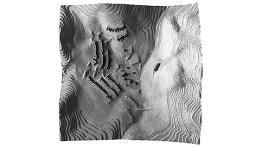

In the year prior to Harry's arrival the town lived through the Gladiator Fire that ate up 16,000 acres. "My entire first semester was spent studying this one fire and trying to figure out how to represent it," Harry says. "The firefighters produce these really amazing tactical fire maps to plan their daily attack. If you are a firefighter from the area, you understand what these maps are conveying. But to someone unfamiliar you are not aware of everything they imply: the interaction of fire with the geography, the terrain, the weather. So I spent my first semester trying to represent that through the techniques of drawing and model making.”

In his final proposal, "Cauterized Terrain," Harry went further by imagining a town that "engages with fire" rather than expending resources on fighting it. "The type of city form that I proposed was one that would require no disaster response when fire burns through. There would be no need for a massive mobilization of resources because the town structure actively engages with the natural process of forest fire." He envisions a town planned in concentric circles of fire engagement. He acknowledges that the proposal is highly theoretical. "I left Crown King with very strong feelings about the ideas of obsolescence and ruin and renewal and rebirth. Coming back, I wanted to express those things in material form. My thesis studies were more about exploring these themes rather than proposing a direct solution to a single problem."

Next up for Harry? He's unsure. "I am looking to move and looking for a place in the profession," he says. He takes a few moments to consider how to sum up his experience at The Cooper Union. "It was something absolutely necessary for me to do. My views and my interests focused during my time here. After six years at the Cooper Union, I feel that the most purposeful and personally satisfying work is that which remains optimistic, with the goal of always bettering the communities we belong to.”