Snapshots of the 2013 Thesis Year

POSTED ON: May 13, 2013

It is the end of the academic year at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, when the fifth-year students present their final, year-long thesis projects. This year, the students and faculty decided to do things a little differently. Unlike years past, where each student's "proposal" has been presented and formally critiqued in the third floor lobby of the Foundation Building, that space, which students had spontaneously painted black some days before, was left empty as a poetic statement on the challenges faced by the institution. Instead students have constructed a wooden table inside the colonnade that runs at ground level along the west side of the building. Pedestrians looking in through the row of windows will see a single piece from each proposal laid out like a banquet. On Wednesday, in place of critiques, students, faculty and guests were invited to engage in a group dialogue about the works, the approach to their presentation and their engagement with the world outside. Here are snapshots of three of those students and their thesis work.

Teddy Kofman, 30, raised in Israel, specialized in electronics through high school, completed his mandatory military service, and began a career in education before his decision to study Architecture. After three years of studies at Tel Aviv University he applied as a transfer student to The Cooper Union, attracted by its pedagogy of self-discovery. "At Cooper you get to explore issues important to you. I was able to clarify my own path.” That path has been very successful, with part of his thesis work winning multiple categories of the Royal Society of Arts US Awards, including a prize of a summer-long paid internship at an architectural firm in New York.

Teddy Kofman, 30, raised in Israel, specialized in electronics through high school, completed his mandatory military service, and began a career in education before his decision to study Architecture. After three years of studies at Tel Aviv University he applied as a transfer student to The Cooper Union, attracted by its pedagogy of self-discovery. "At Cooper you get to explore issues important to you. I was able to clarify my own path.” That path has been very successful, with part of his thesis work winning multiple categories of the Royal Society of Arts US Awards, including a prize of a summer-long paid internship at an architectural firm in New York.

The winning entry, 1 Station 4 Trees, aims at the problem of the urban expansion of Houston, Texas, and the resultant loss of necessary prairie and forest land. “As the city grows it threatens the forest and prairie, and is consequently prone to more frequent flooding and higher levels of air pollution,” Kofman says. “Urban expansion leads to deteriorated living conditions for residents. My focus is to propose an urban strategy as well as a small-scale design that could be implemented throughout the city.” Kofman’s winning proposal features a transit station that harvests dew and rainwater and uses it to irrigate surrounding patches of trees, as well as providing a habitat for urban wildlife. Together the shelters would offset the impact of expansion by creating and supporting a biological connection between proposed “Islands” of urban forest and prairie.

From Teddy Kofman's thesis: an urban "forest" proposal in downtown Houston, TX.

From Teddy Kofman's thesis: an urban "forest" proposal in downtown Houston, TX.

The proposal, which will include drawings, models, writings and photography, is based significantly on research conducted in Houston after Kofman received the William Cooper Mack Fellowship, a travel grant awarded to architecture undergraduates. "This was incredibly helpful," Kofman says. "In Houston I met with a number of local professionals including architects, environmentalists and urban planners. Houston is gigantic. It was difficult to comprehend without going there and seeing the city first hand. My first few days there were pretty miserable. It's raining. It's humid. All the places I find myself in are unpleasant. But through casual conversations with locals and the interviews I had arranged I was able to discover a fascinating city."

After graduation, Kofman hopes to continue his study of architecture and gain additional professional experience while incorporating other interests he wants to pursue. "I hope to work in an environment that will be challenging and educating through which I’ll be able to grow as an architect, alongside taking time to travel and work on photography projects" he says. But he will have fond memories of his time at Cooper, in spite of the work load. "My first impression of Cooper was that it most resembled the idea of academy as I had imagined it and hoped it would be. There are ongoing discussions and debates that challenge your thoughts and constantly make you ask questions. It's exhausting and hard but at the same time it pulls you in.”

The youngest member of the School of Architecture's class of 2013, Eze Imade Eribo, turns 22 this month and originally hails from Nigeria. The precocious Eribo might have been here sooner but after graduating from high school at age 16, during which time she had a book published, Pieces of Me: A Collection of Poems, Short Stories and a Play (Neposit Books; 2007), she took a year off. "My initial career path was medicine," she says, "but after getting into some colleges, I changed my mind at the last minute so I had to re-start my applications all over. I was drawn to art, writing, music, poetry, drama and I just felt like I needed to do something that was a comingling of all those things. Architecture to me, was the closest and in many ways a celebration of all of those."

The youngest member of the School of Architecture's class of 2013, Eze Imade Eribo, turns 22 this month and originally hails from Nigeria. The precocious Eribo might have been here sooner but after graduating from high school at age 16, during which time she had a book published, Pieces of Me: A Collection of Poems, Short Stories and a Play (Neposit Books; 2007), she took a year off. "My initial career path was medicine," she says, "but after getting into some colleges, I changed my mind at the last minute so I had to re-start my applications all over. I was drawn to art, writing, music, poetry, drama and I just felt like I needed to do something that was a comingling of all those things. Architecture to me, was the closest and in many ways a celebration of all of those."

Stilt housing in the Bakassi peninsula. Photo courtesy Eze Imade Eribo

Stilt housing in the Bakassi peninsula. Photo courtesy Eze Imade Eribo

Eribo's thesis site is the Bakassi peninsula, a disputed territory between Nigeria and Cameroon, now governed by the latter after a 2006 transfer of sovereignty on the heels of a judgment by the International Court of Justice. Since then, Eribo says, the Cameroonian government has been, "trying to eradicate the Nigerians that have been there for years. It means displacement, killings, terror and identity loss. It's getting people out of their livelihood and their ancestral homes." Another recipient of the William Cooper Mack fellowship, Eribo travelled there and discovered that political instability was not the only hardship. A number of environmental challenges became clear, including the lack of potable water and the practice of smoking fish, the main export of Bakassi, which pollutes the air and subjects the wooden stilt housing to the risk of fire.

Bamboo rafts in Bakassi peninsula. Photo courtesy Eze Imade Eribo

Bamboo rafts in Bakassi peninsula. Photo courtesy Eze Imade Eribo

"I wanted to find a way of addressing those problems and still talk about the larger political issue without getting into trouble. In Africa you can't directly talk about politics, but through art, it is forgivable." Eribo says. Her thesis, Reconstructing the Banal, proposes a solution using an indigenous form of transportation: the bamboo raft. "It's designed as a smoke house and water filtration site but it's also actually a secret radio station," still the main method of mass communication on the peninsula, she says. As the raft travels it broadcasts factual stories of conflict rewritten by the people who bear witness into the more politically acceptable form of myths and tales. [Listen to one: "The Rape of the Bride", from Eribo's proposal] "This is designed to be a practicable idea," she says, "I have designed these systems based on local materials and techniques. Everything is being knotted and woven and the materials and equipment are easy to find there. I wanted it to be a community effort, encouraging self-reliance from local means and resources, so they don't have to depend on the government."

Though Eribo plans on pursuing other goals, for now she will stay open-ended, on a journey of self-discovery fostered by her time at Cooper. "It's beyond anything I ever imagined. I feel like everything I was looking for I got and ten times more," she says of her time here. "It's not about training you to a specific job. It's about really discovering these things that are particular and unique to you and how these things can impact our society. I feel like I found myself. A lot of the things that I loved to do, I am still doing but at a higher, more aware and passionate level. I'm a different person now but I am also a better version of the person who I was before."

David Varon, 23, graduated from Miami's lauded magnet school Design Architecture Senior High, which has produced a number of Cooper students, including James Sprang who we profiled in the School of Art senior snapshots. Originally from Colombia, he arrived in the U.S. at age seven and thought he would follow in his engineer father's footsteps until an art teacher pushed him in another direction. His thesis, A Tactical Vision for the Arctic, began when his mother did something he describes as "crazy:" she joined the military and got stationed in Alaska.

David Varon, 23, graduated from Miami's lauded magnet school Design Architecture Senior High, which has produced a number of Cooper students, including James Sprang who we profiled in the School of Art senior snapshots. Originally from Colombia, he arrived in the U.S. at age seven and thought he would follow in his engineer father's footsteps until an art teacher pushed him in another direction. His thesis, A Tactical Vision for the Arctic, began when his mother did something he describes as "crazy:" she joined the military and got stationed in Alaska.

From that Alaska connection, he proposes a system for creating artificial ice islands off the coast of Barrow, Alaska, America's northern-most city. "That area is ground zero for changes in temperature," he says. "Ice is melting. Polar bears are dying." His proposal aims to rebuild the albedo effect of ice reflecting the sun's radiation. The lack of ice causes the water to absorb more heat, causing more ice to melt in a spiral of negative environmental consequences. In his fourth year, Varon traveled to the Aleutian Islands of Alaska as a recipient of the Benjamin Menschel Fellowship, which is awarded to any student from the three schools at Cooper Union. While in Alaska he researched World War 2-era military construction, fueling his interests in the Alaskan landscape and its transformation over time through human intervention.

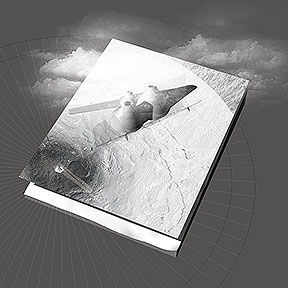

From David Varon's thesis: an axonometric view of a center pivot machine building an ice island.

From David Varon's thesis: an axonometric view of a center pivot machine building an ice island.

For his thesis, he says, "I'm presenting a book of drawings and maps. It's a book that will have some of the patents that I looked into as well as drawings of the proposed island-building equipment -- how you put them together, how you take them apart -- along with a process for what would be involved." He re-casts the center pivot irrigation system that creates the crop circles seen during cross-country flights, mounting them on flotation devices. A sump pump sucks up sea water and sprays it out so it freezes. "The other thing I like about the ice idea is that you can cast it into whatever topography you want. It's basically like a giant 3-D printer but using natural materials." His thesis work made him another RSA US awards prize-winner.

Varon talks about his time at Cooper as being difficult, but rewarding. He says he chose Cooper because, "I liked what was going on here and the people who worked here. Being in a class of 30 in New York City is pretty awesome." For his next step he has chosen to do something he describes as being as crazy as his mother's move to Alaska. "I applied for Teach for America and I got accepted," he says, his eyes still widening in disbelief. "It's a two-year program where college graduates work in urban area high schools. I'm the first person from Cooper to go to Teach for America, they tell me. I'm going to be a math teacher in Miami. It will be a good break after doing architecture and design for five years, and will help me plan for whatever is coming next."