Open Books, Open Process

POSTED ON: July 30, 2025

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue of At Cooper magazine.

Architecture has a long history of engaging with design and space Piranesi’s etchings, Hugh Ferriss’s drawings, and Super Studio’s collages, to name just a few, all contributed to architectural discourse without a single blueprint or ground breaking.

In recent years, Acting Dean Hayley Eber has worked to expand the course offerings at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture to reflect that history, give students more ways to represent their ideas, and eschew the simplistic dichotomy of analog versus digital. “In reality,” she says, “a wide range of tools and techniques exist between these two modes. Courses in print and bookmaking encourage students to create architectural images and artifacts that transcend this false dichotomy.”

Three courses recently offered—a printmaking class, another dedicated to book design, and one focused on producing a student publication—let students explore architectural ideas using methods outside of traditional architectural drawings and model making.

Writing and publishing, of course, have always been an integral piece of the development of architectural thought, and two courses last fall explored that rich history in quite different ways. For Design of the Book, a project-based seminar taught by Laura Coombs and Phillip Denny, students considered book design on two fronts: via research, to understand the evolution of book forms and their making throughout history; and through production, designing and creating books using contemporary processes. Meeting weekly in the Cooper library, students analyzed books as architectural objects, investigating the materiality of the printed page while examining print technologies through the ages. Eber notes that the class is co-taught by an architectural historian and a graphic designer, and “the course examines the fundamental relationship between these two interconnected design disciplines.”

Joanna Joseph, assistant director of Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, taught a Fall 2024 class on producing a publication in which she introduced students to historical and contemporary models of architecture and design publishing. Together with archivist Chris Dierks, associate director of Cooper’s Architecture Archive, members of the class considered questions of audience, circulation, distribution, and form. Students applied these lessons to their own proposals for a school publication. They paid particular attention to Cooper’s history of discursive practice, connecting with the archive to examine past student publishing work, as well as the rich tradition of critical, creative, and visual production across Cooper and across New York City. “We’re now looking at the work produced [in the class], to determine what might be possible for a publication,” said Eber.

A third class that explores the relationship between publication and architecture is called First Edition, developed and taught by Clara Syme, Owen Nichols, and Gus Crain, a 2024 graduate of the school of architecture.

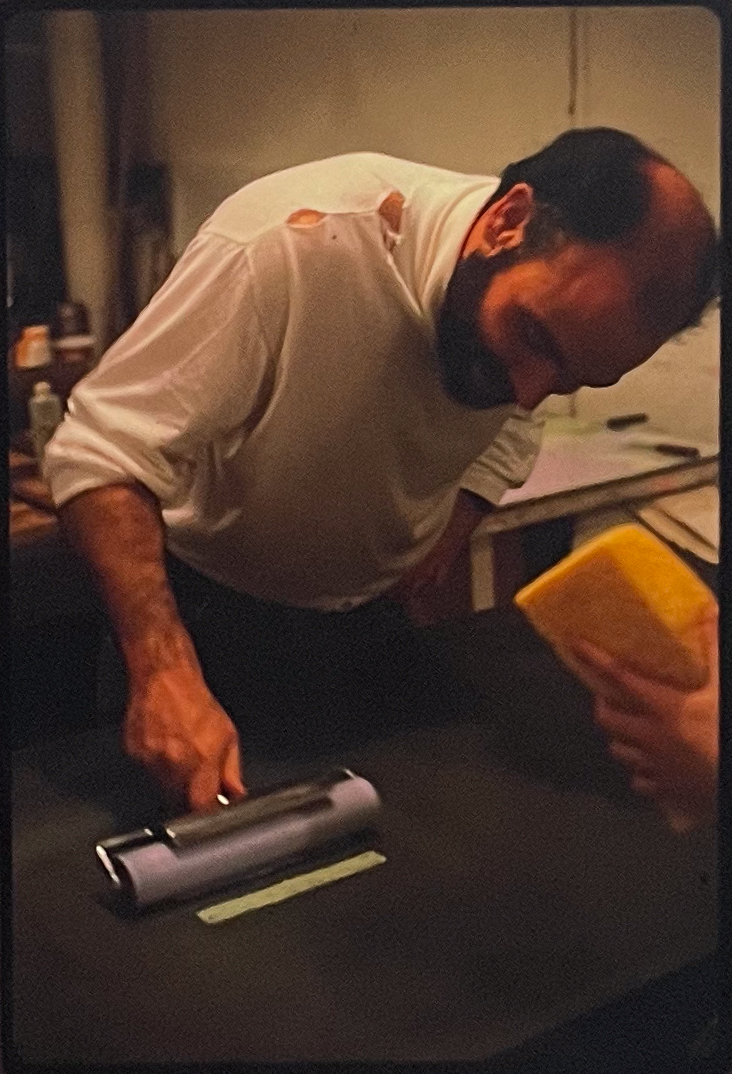

The class is a collaboration with a83 Gallery, where students met to learn how to screen print, a process that has some advantages over digital tools.

Sydney Mina, a fifth-year architecture student who took the class, said, “I was able to approach concepts in my thesis in new ways by not only layering with the ink but layering papers and using different paper types. By doing so, I was challenged to think about my approach to my thesis more critically.”

Besides teaching a new technique for representing architectural ideas, the course connected students to an important moment in recent architectural history: a83 is housed in a building where Nichols’s father, John Nichols, made prints for himself and other architects through the 1980s and ’90s. In her book, Architecture Itself and Other Postmodernization Effects, Sylvia Lavin described the impact of Nichols’s work: “Insofar as the relationship between art and architecture is not only defined in relation to medium or discipline but also at the intersection between people and production, John Nichols’s Printmakers and Publishers at 83 Grand Street, in New York City, is where they came together.” His clients included Denise Scott Brown, Michael Graves, and Thom Mayne, architect of 41 Cooper Square.

Symes, who with Owen Nichols is a co-principal of the architecture firm Chibbernoonie, said that she and Nichols took inspiration from that work and when they met Dean Eber to discuss developing a course, “it felt natural that the class should explore both a conceptual approach to architectural images and a hands-on, physical engagement with their production.” At their class’s final review last December, Cooper fifth-year students and two exchange students from the Royal Danish Academy pinned up diptychs meant to communicate different aspects of their thesis projects. They’d already been working on their theses for a semester and now were reflecting on insights gained through their print work.

For Patrick Rearden, the silk-screening process heightened his ability to really investigate an image as opposed to the techniques used with vector lines or JPEG images: “Images on a computer are transferred onto paper via a plotter with little to no human involvement in between. There’s something to be said about the time and in-between state required of screen printing. For me, it prompted a deeper level of engagement with the image, which made me consider the richness of the site and view.” He also pointed out that making a print is a process that “diverged from the overwhelming sense of infinite and immediately accessible content brought about by data centers and what they contain. I used the least amount of information to create a print of a subject that is all about excessive information.”

Jasper Townsend’s project considers the other side of the tech spectrum, the infrastructure of radio. For his diptych, Townsend created a day and night view of a radio tower. He needed to find a way to represent sound waves and found that the additive process of making a silkscreen print lent itself to the task. “By depositing dots over and over, a constellation of waves emerged. The use of white on black was only made possible through the silkscreen; inkjet plotters don’t have the capability to print white. The ways halftones are used, the scale of dots, and the assignment of producing a diptych through the silkscreen forced me to clarify my thoughts, and to develop a process of working consistent with that.”

His discoveries were very much in keeping with the approach Syme and Nichols used when designing the course. “The real challenge and learning opportunity for architects in printmaking lies in the necessity of careful consideration and editing,” said Symes. “Because each separation in printmaking requires significant time and effort, students learn to economize their labor, which teaches them to refine and distill their images.”

That slow, tactile aspect of the work perhaps also holds a certain appeal for a generation of students raised on digital technology. As a respite from the “seemingly endless amount of data and content” described by Reardon, print and bookmaking demand students’ focused attention and, above all, the patience to see where it leads.