Diane Lewis: Reader of Urbanity

POSTED ON: March 29, 2018

Diane Lewis at a Design IV review, Fall 2008

Dean Nader Tehrani penned an all-encompassing tribute to longtime Cooper Union Professor Diane Lewis, who passed away in 2017. Placing Lewis firmly at the center of The Cooper Union’s pedagogical direction, Tehrani memorializes Lewis in the context of her collaborators, colleagues, students and her city – New York. The text below was published in the Journal of Architectural Education, Volume 72, 2018 – Issue 1 – March 2018: a/to project.

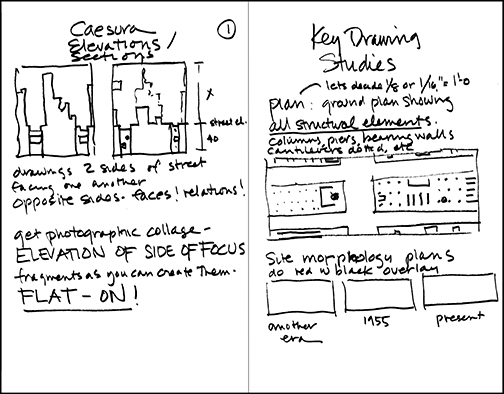

[Above: Diane Lewis, Civic Caesura Project Sketches Design IV, Spring 2016.] With the publication of Open City: Existential Urbanity, Diane Lewis brought fourteen years of research and design to print. In doing so, she also brought closure to a life’s work of building connections between her thinking, teaching and practice. Indeed, behind an intense and illustrious career, Lewis defined an era of The Cooper Union that not only precedes me, but has come to transition as many of its exemplary voices have moved on. John Hejduk (2000) and Lebbeus Woods (2012) passed on long before their time was due, each leaving behind a significant intellectual vacuum. Raimund Abraham (2010) left Cooper Union in 2002, but also passed away prematurely. Others such as Peter Eisenman and Ricardo Scofidio live on productively, but moved on from Cooper Union in 2006 and 2007 respectively. In the Spring of 2017, the untimely loss of Diane Lewis left the school with only Anthony Vidler and Diana Agrest as full-time professors; it also left the Cooper community with the recognition that an important part of its link to an era had come to pass, and was in need of historical recognition.

As one of the co-editors of Education of an Architect, Lewis was well-aware of her responsibility to the larger arc of pedagogical commitments to the school. That responsibility was also colored by a series of intellectual tropes that were entirely her own, the result of her years as a student, teacher and collaborator of the team-teaching tradition that defined this era. Thus, as she worked on her final book, she engaged a range of other voices whose presence at Cooper Union had become an extension of her own legacy as mentor and collaborator—among the myriads, Daniel Meridor, Peter Schubert, Mersiha Veledar and Daniel Sherer, who worked within Cooper Union, but also an extended cohort of intellectuals such as Barry Bergdoll, Merrill Elam, Calvin Tsao and Roger Duffy, who brought critical insight from intellectual boundaries beyond. For this reason, it is maybe implausible for me to attempt to capture the panoramic picture of these individuals in one text, but they serve to underscore the ability of one individual, Diane Lewis, to capture such intellectual range in a community of voices.

[Above: Diane Lewis with colleague Peter Schubert - Design IV review, Spring 2006.] As an avid scholar of the Greek mythologies and the classics, Lewis transposed her passion for reading onto the grain of the city itself. Indeed, her discovery of Mario Morini’s Atlas of Urban History is a salient launching point of her academic infatuation of “the plan” as a repository of knowledge. Her encyclopedic knowledge of cities from “Preistoria to the Ottocento” also demonstrated a curiosity of interpreting the “score” of each culture, its civilization and the public audience each has sponsored, insofar as they could be read into the fabric of these planimetric documents. It is, then, maybe no accident that even with the onslaught of digital modeling and the transformations of our ability to envision the city, much of her pedagogical efforts maintained the fecundity of certain representational instruments—plan, section and model are key investments of each of the projects documented in the book.

A fellow of the American Academy in Rome, Lewis came to urbanism with a deep appreciation of the complexities that each city brings to the advent of history—layered as it were with strata, each from a different epoch in the lamina that is the palimpsest of the archaeological remains of the ancient before it. An overt and challenging task to take on in Rome, Lewis would approach her own New York City with this same lens, drawing out of its section the multiple narratives that would otherwise lay dormant in the folds of its infrastructure. A child of the punk era, she was also a native street kid, conversant with the 70’s, CBGB and the beat that the street offered as part of her cultural reading of the city. Out of the iron grid of New York, she discovered a configuration that, on one hand, refused the kind of figuration that was overt and mostly explicit in the Roman sphere. On the other hand, within the framework of her analytical approach—with piercing x-ray eyes—she discovered itineraries, figures, associations and larger urban amalgams that would otherwise remain encrypted within the diffused mat condition of the Manhattan grid. A key methodological bias in this project was her interest in establishing a relationship between institutions and the civic spaces they sponsored, or by which they were defined. In her seminal drawing of the mid-town grid, she identifies a walk from Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building to Gordon Bunschaft’s Lever House just north, followed by McKim Mead and White’s Racquet and Tennis Club, to Zion and Breen’s Paley Park to the west, Isamu Noguchi’s lobby at 666 5th Avenue, then the newest incarnation of the Museum of Modern Art by Taniguchi and finally leading to the CBS tower by Saarinen. Each building is shown to be part of an architectural commitment to urbanism, defined by the respective spaces they sponsor as part of their agency. What’s startling is how this seemingly benign itinerary becomes a radical pedagogical vehicle through which larger voids are discovered in the minds of Diane’s students. Moreover, not only are these urban figures uncovered as such, but they are part of a projective task; from the Italian, Lewis borrows the act of emptying or voiding out, in the verb “vuotare:” excavating not so much an existing ruin, but a project yet to be anticipated.

Lewis highlights two instrumental processes in her study of the urban project, one rooted in Abstraction and the other in Surrealism. If the former gains its traction from the erasure and distillation of information, the latter delivers a new form of cognition through mis-readings and unanticipated associations. In tandem, they acknowledge the conscious and the unconscious, the rational and the irrational as an irrevocable part of the design equation. Moreover, they demonstrate the latitude gained from a representational realm that is the result of an expanded historical and aesthetic framework. Potentially antithetical from a philosophical point of view, Lewis brings the abstract and the surreal onto the same pedagogical plane, both in service of a deeper reading of the urban condition.

Beyond Manhattan as an abstraction, the many years of studio research took on cultural events that occupied our imagination with equal urgency as they did with the patient poise of historical insight. A myriad of themes, from Post Blast Lower Manhattan to the Civic Still Life, to Cities of Catastrophe: From Atlantis to New Orleans and Tower/Acropolis, and from Autonomies and Spazialismo to The Bowery: Architect and Continuum, one can see the many ways in which Lewis interpreted history as an ongoing project: inspecting the past with the depth of curiosity, while also reacting to the predicaments of the current state of affairs with elastic immediacy. For history to be relevant, it also had to be present, or even more, somehow projective into a possible future.

Lewis left The Cooper Union in mid-semester of Spring 2017, and she was not to return, passing away on the first day of final reviews. However, she left behind a profound intellectual legacy that is here to stay. The combination of fierce charisma, a fighting spirit and a stubborn intellectual posture defined her living days and, in hindsight, we come to appreciate the sum of it as an ambition for all of us to emulate. A tireless protagonist, she would conduct reviews that would end some five hours after the end of the day; her love of debate through the jousting of words, ideas and positions defined the many events she hosted. Lewis left behind many things, but her most recent book, Open City: Existential Urbanity will serve as a document of the many the pedagogies she explored, the constellations of ideas she sponsored and the platforms of debate she invented.