Thesis-Year Snapshots 2017

POSTED ON: May 15, 2017

In the second of our annual series on members of the year's graduating class [see part one] we turn our attentions to the fifth year students of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. Meet Stephanie Restrepo, Aimilios Davlantis Lo, and Piao Liu.

Months before the presidential election, Stephanie Restrepo knew that she wanted to research walls, those architectural elements that have gotten so much press in recent days. “We think of walls as dividers, but I wanted to find out if there was some way I could use a wall to integrate spaces,” she said. That question could be said to be the central one Stephanie has grappled with throughout her time at Cooper, an experience that while initially challenging, proved to be hugely gratifying.

Months before the presidential election, Stephanie Restrepo knew that she wanted to research walls, those architectural elements that have gotten so much press in recent days. “We think of walls as dividers, but I wanted to find out if there was some way I could use a wall to integrate spaces,” she said. That question could be said to be the central one Stephanie has grappled with throughout her time at Cooper, an experience that while initially challenging, proved to be hugely gratifying.

Born in Colombia and raised in Miami, Stephanie learned about the school from one of her teachers at Design and Architecture Senior High School. When she gained admission, she immediately accepted, though she’d never visited New York or the school.

Her first year was a struggle, and she seriously considered leaving. “I just wasn’t sure if this was where I was supposed to be. After talking to Professor James Lowder, I made a commitment to stay and continue working.” Diane Lewis, the venerable professor of architecture who passed away this month, was also instrumental in shaping Stephanie's time at Cooper. “Diane embodied and lived architecture. She spoke about architecture with so much fervor it was contagious. Talking to her about architecture was almost spiritual. She helped me see the what architecture could really do.”

Her thesis project, entitled “El Muro de Neblina,” was inspired by the late Lebbeus Woods’ exploration of walls. She set out to find out if a wall could act as a way to bring people together instead of imposing separation. Stephanie received the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship award, which she used to travel from San Diego to Big Bend, Texas documenting what exists of the wall between Mexico and the United States. She gathered her findings in a booklet richly illustrated with her photographs and drawings as well as satellite maps.

After researching dozens of walls around the world, Stephanie concentrated on one that sits on a mountain ridge in Lima, Peru that when seen from an aerial view, starkly divides an upper-class area, known as Las Casuarinas, from an impoverished one, Pamplona Alta. “I was interested in it not only because there is such a blatant difference between the two sides, but also because the wall is redundant—the two areas are already divided by topography.”

Stephanie used access to clean water as a means to highlight economic injustice. Each wealthy resident enjoys 395 liters of water per day to their lawns lush and swim in their pools while on the Pamplona Alta residents live on 20 liters of water per day, barely enough to cook and keep clean.

The wall Stephanie designed for the site addresses both physical and metaphoric needs of the community. Constructed of mesh, the wall takes advantage of the area’s climate by collecting water from humidity. Known as a fog harvester, such walls have been used since antiquity to collect condensation and reserve water. In Stephanie’s plan, the water droplets attach to the mesh wall and make their way via gravity into underground cisterns where water is collected and distributed throughout the community. The wall undulates in the landscape so at certain points it acts more like water infrastructure and other points transforming into public space where residents from Pamplona Alta can gather.

In part, Stephanie’s interest in socially conscious work stems from her time at Cooper. A freshman in the fall of 2012, she and her classmates witnessed and participated in the protests to keep Cooper tuition-free. “It was a valuable lesson in activism. Our students are vocal, and I appreciate that. I am a student who could never have gone to Cooper if I’d had to pay tuition. There are so many high school students who want to go to school and have what it takes to succeed but cannot afford it.“

Currently an intern with WeWork, a workspace design firm, she has not yet decided her next move after Cooper. She knows, however, that she would like to work for a non-profit agency to use design in ways that improve life for the underrepresented. “MASS Design Group spoke at Cooper,” she says, referring to a Boston-based firm, “about partnering with government agencies. They taught people to be master masons. They are thinking about the role of the architect once the architect is gone. That really appeals to me.”

Aimilios Davlantis Lo applied to The Cooper Union at the urging of an advisor at the International Baccalaureate school he attended in Athens, Greece, where he grew up as the son of two practicing architects. Once he started work on the home test, he knew that Cooper was the right place for him. “I found the home test to be a provocative challenge” he says. As a student who tends to dive deep into subjects that engage him, he was excited to attend a school that encourages thorough and wide-ranging investigation.

Aimilios Davlantis Lo applied to The Cooper Union at the urging of an advisor at the International Baccalaureate school he attended in Athens, Greece, where he grew up as the son of two practicing architects. Once he started work on the home test, he knew that Cooper was the right place for him. “I found the home test to be a provocative challenge” he says. As a student who tends to dive deep into subjects that engage him, he was excited to attend a school that encourages thorough and wide-ranging investigation.

His thesis is a case in point: intrigued by the possibility of designing a structure based on joints, Emil, as he prefers to be called, started his year-long study by designing a disassemblable chair with a structural system dependent upon disguised fastening hardware. Emil needed to create specific tools to make the joint system, so he designed and manufactured them himself. His apartment, he says, is a mini-machine shop where he fashions a whole range of tools meant to perform very specific jobs for various projects.

In the second semester, he continued his thesis project by designing a carbon-fiber tower sited in the Namib Desert in Namibia. In Emil’s conception, two long, rammed-earth walls would be constructed and covered by canvas as the ceiling. This would form the factory to produce the light-weight carbon fiber parts. These would be stored on the canvas roof where the tower would be horizontally constructed. One end would be fitted with a weight next to a 300-foot excavated foundation. Upon completion of the tower, the canvas would be detached from the factory walls and attached to the tower. At this point, as Emil’s mentor Powell Draper put it, “the poetry of the site” would come in to play: a severe windstorm, the likes of which are expected in the Namib Desert every 10 years or so, would inflate the sails and help lift the mile-long tower, which would then be tipped into the deep earthen trench. The “joint”—the meeting of tower and earth—would finally be raised like an obelisk by both humans and nature.

As if he wasn't busy enough, Emil also made time this year to submit a work to the inaugural David Yurman Young Artist Prize. Created by the founder of the eponymous luxury jewelry house, the prize committee has awarded Emil a $10,000 scholarship. For the contest, Emil designed a bronze cylinder with a pinched center made by a Computer Numerical Control (CNC) router. In his accompanying narrative, he noted that many people perceive computer-made objects as cold and unfeeling, but as he put it, “This piece seeks to reconsider this. While it is mostly a conventionally machine-made shape, it features a pinch in its middle that feels very haptic, as if pinched in clay or skin. The bronze, which is usually so indifferent to change, seems as if it were effortlessly malleable. Computer controlled machines make it possible for us to create anything we can imagine.”

Emil finds that what has been the most enduring lesson from his time at Cooper is that solutions are complex and multiple, as are working relationships. “You see how a group of people work together, how that can be complicated, but also very rewarding.” He found that the many hours of work he put in to his education were extremely worthwhile and satisfying. “I believe the most impactful thing you can do is to pursue what you do best.”

Emil expects that one day he will work with his parents in their Athens practice, though his immediate plans are to attend Harvard’s Graduate School of Design starting this fall. While he’s not sure about the specifics of the work he’ll do there, he imagines that the investigations he started at Cooper will be with him for a lifetime: “Your thesis project never really ends, does it?”

A native of Chongqing, China, Piao Liu knew she wanted to study architecture after a devastating 2008 earthquake occurred in Wenchuan in Sichuan, China, causing the collapse of hundreds of buildings that killed almost 70,000 people. “Those buildings weren’t equipped for that level earthquake. Buildings are meant to protect, and it’s so tragic that those weren’t safe. It made me realize how critical design is and how architecture can change society. It’s a humanitarian way of thinking.”

A native of Chongqing, China, Piao Liu knew she wanted to study architecture after a devastating 2008 earthquake occurred in Wenchuan in Sichuan, China, causing the collapse of hundreds of buildings that killed almost 70,000 people. “Those buildings weren’t equipped for that level earthquake. Buildings are meant to protect, and it’s so tragic that those weren’t safe. It made me realize how critical design is and how architecture can change society. It’s a humanitarian way of thinking.”

She earned her first undergraduate degree at the University of Manitoba, where she graduated with a degree in Environmental Design. Still, she says, Cooper is legendary for architecture, and she was further inspired by reading founding dean John Hejduk's Education of an Architect where “the work is very different than you’d see elsewhere.” When she was accepted to Cooper, she began as a second-year student. Did she mind committing to an additional four years of course work? “No! Cooper is very special. Because it’s a small program it’s tailored to your ideas, which is a great advantage for getting feedback.” She characterizes herself as someone who likes to spend a lot of time pondering difficult, open-ended questions, and Cooper was a place that encouraged her to make those intellectual explorations.

For her thesis, Piao studied the world’s time zones and the political and natural forces that determine them. Some, she discovered, had been created as a result of mountain ranges or bodies of water; others, like China and India, were based solely on political boundaries that seemed to completely ignore natural divisions. While today’s time zones are determined by lines of longitude–or meridians—Piao wondered what would happen if latitude were added to further delineate a time zone. Taking that idea further, she imagined time zones determined only by each individual’s location in space. If we all had our own time zones, she asked, how would that change our relationship to architecture and monuments? Further, how would that change what architects designed? As she put it in her thesis proposal, her project is about “the struggle between the unsympathetic time line that imposes rational demarcations on to the built environment and the timeless architectures that define their own ultimate, autonomy and distort the time line.”

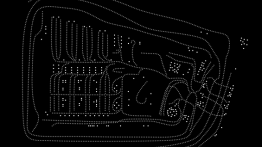

Piao then applied her research to Roosevelt Island, a site she chose to test the question, Can architecture override a universal, arbitrary system? The island, which lies between Manhattan and Queens, became residential in the 1970s and is reached via public transportation by subway or tram. “The inaccessibility of the island creates a space-time incoherence,” Piao notes, since “the subway didn’t get built until a certain number of people had already settled on the island.” The tram also wasn’t built until 1976, so the only way to get there was by car over the Queensboro and Roosevelt Island bridges. “So it is a very specific case for my thesis topic, public time and private time.”

After graduation, she ideally would like to travel more and perhaps keep volunteering with Habitat for Humanity, which she has done for the last few years. There is, of course, the pesky business of supporting herself, but as someone who loves to investigate ideas and places, she expects to keep looking for the answers to enigmatic, hypothetical questions.