Rooms Without Walls

POSTED ON: November 10, 2025

Cooper Professor Leads Met Redesign

This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue of At Cooper magazine.

While the cool detachment of white box exhibition practices, today’s museums are reassessing the alleged neutrality of white walls and ceilings. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) has embarked on several major projects to better contextualize its astounding collections of art and cultural objects, one of them led by a Cooper faculty member, Professor Nader Tehrani.

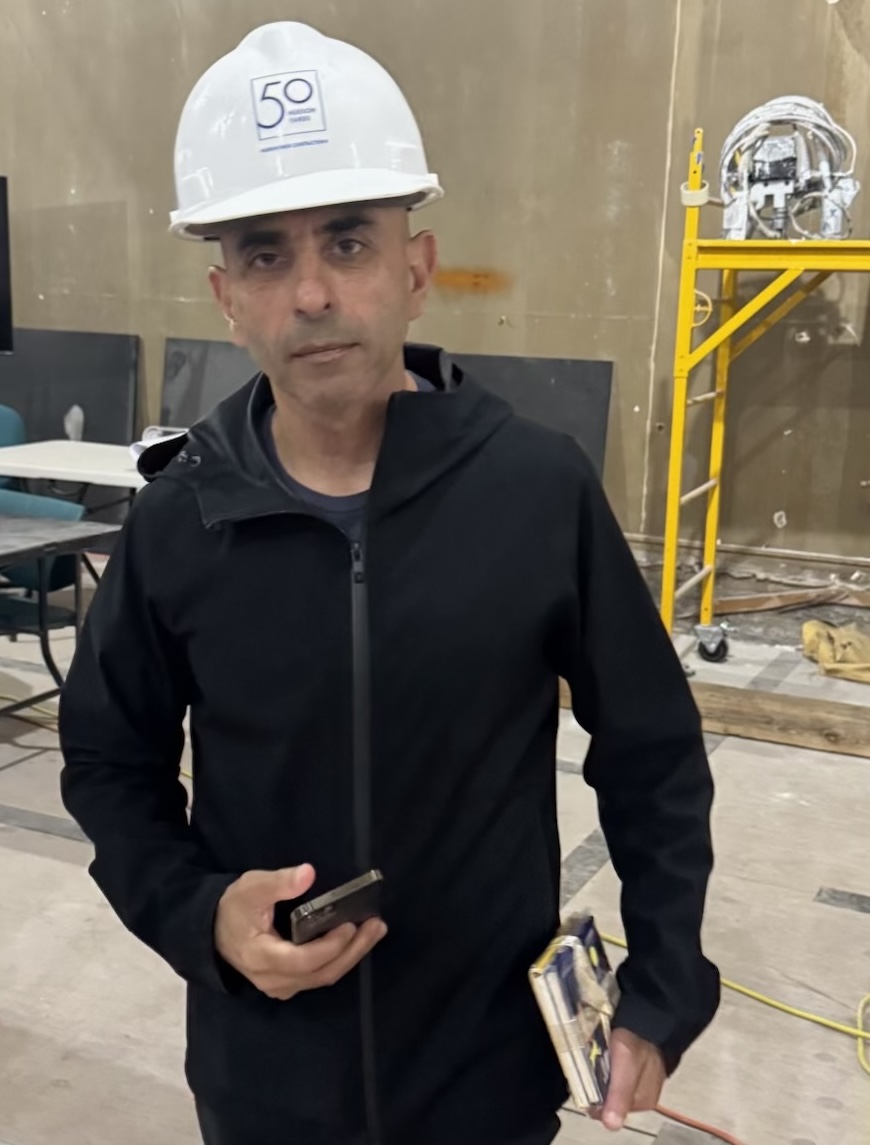

In 2022, the Met chose Tehrani’s firm NADAAA to reimagine its galleries of Art of Ancient West Asia and Ancient Cyprus, formerly known as Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art. The redesign, like the name change, addresses the past curatorial practices of the museum, which framed the objects and history of the region from a European perspective.

“The Met isn’t just a building,” Tehrani said in a presentation about the redesign, a 15,000-square-foot project. Comparing it to Diocletian’s Palace in the contemporary city of Split, he described the museum as “a piece of urbanism.”

That vision of the Met as essential city infrastructure animated Tehrani’s design. It connects the galleries to the Great Hall Balcony while drawing both spatial and metaphoric associations with the Department of Asian Art to the north, the Galleries for Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia to the south, and the 19th/20th Century European Painting & Sculpture Galleries to the west.

The $40 million project, currently under construction, is part of a larger set of renovations being undertaken by the museum, including the newly reopened Michael C. Rockefeller Wing by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture and a new wing for modern and contemporary art by Frida Escobedo Studio. The museum is aiming to create galleries that are in step with current scholarship and provide far greater context for the history and provenance of the objects on display.

At the launch of a set of talks about the museum’s proposed new galleries, Max Hollein, the Met’s director, said “[The new galleries] will present art in a better way: They will tell new stories, new narratives. They will also create new spatial surroundings for our visitors and for our experience with art.”

Tehrani, who has taught at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture since 2015 and served as dean up until 2022, sees the redesigned galleries as a response to what he calls “the rescripting of the narratives of ancient culture.” He has been closely collaborating with Met curators Kim Benzel and Sean Hemingway, who have set out to eschew a top-down perspective in favor of those that highlight cross-cultural influences and the objects of everyday life. NADAAA’s redesign of the space, the first since the early 1980s, reflects that curatorial approach, framing the region’s history as a response to geography, natural resources, and long-term cultural shifts and influences. When discussing the Met galleries redesign, Tehrani has referred to the writings of Fernand Braudel, a historian whose 1949 study, The Mediterranean, analyzed daily practices of work, religion, trade, and community. Braudel’s method, akin to that of the Met curators, garnered a fuller, more nuanced history of the region than traditional accounts that focused solely on the impact of rulers and other powerful figures.

The museum’s collection of Ancient West Asian art includes work made between 8,000 BCE to the seventh century CE made in the vast region that extends from the Eastern Mediterranean through the Fertile Crescent (current-day Palestine, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and parts of Iran) to the Zagros Mountains and beyond to Central Asia. Of the varied narratives, the new exhibitions will bring focus to the materials of the approximate 7,000 works on display including clay, copper, bronze, gold, silver, limestone, and lapis lazuli while considering the cultural changes provoked by their discovery, extraction, and use. New means and methods of fabrication were born out of these very materials, bearing witness to emerging crafts and trades and giving rise to objects of daily use and religious devotion. For example, in the Cyprus galleries, a 70-kilogram ingot of copper will be displayed next to a bronze tripod to represent the island’s fame as a copper exporter during antiquity. (Its ancient Greek name, Kupros, means copper.)

Benzel, curator in charge of the Ancient Near Eastern Art, said of the redesign: “By expanding conversations to be more trans-cultural, and by engaging with heritage communities and diaspora groups, we will be able to highlight alternative narratives and contextualize ancient objects within contemporary discourse.”

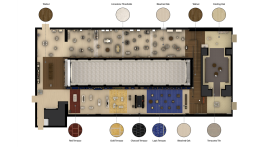

Tehrani underscores the galleries’ central location by focusing on circulation, with four entry points for moving through the gallery following what NADAAA calls the torus wall, denoted by red and deep lapis, colors chosen to reflect the mineral resources of the area. At the same time, the marked use of color works to counter the vision of the white-box gallery as a neutral, objective space. In fact, in many ways the redesign by Tehrani’s firm asks visitors to think about the act of collecting and the colonial history that brought these collections into being.

The torus wall acts as a fluid connection through the open-plan galleries, yet along this promenade Tehrani has created what he calls carpets or ribbons that, through their use of materials, evoke rooms without walls: wood floors for the Cypriot galleries and terrazzo for the Ancient West Asia, with limestone as the connective tissue for both. These spatial subdivisions maintain the open floor plan while punctuating the curatorial narrative.

The Art of Ancient Cyprus galleries, following the period from 2,500 BCE to 300 CE, feature an exceptional collection of funerary monuments and votive sculptures, as well as stone sarcophagi, four of which will be on permanent display. Made up of the museum’s Cesnola Collection (acquired in 1872 and amounting to more than 6,000 objects), these new galleries will create narratives related to the region’s materials, funerary rituals, religion, and identities. The redesign focuses on Cyprus as a crossroads with influences from the ancient Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans. Visitors will follow the ways the island’s cultural output altered over time.

Essential to Tehrani’s design is the galleries’ ceiling plan. Undulating and slotted, their vaults serve two functions: to mask critical functional elements of the spaces related to lighting, HVAC, security, and fire systems; and to mark shifts in the exhibition narrative. “The 19th century wanted to taxonomize everything,” Tehrani explains, but that approach negates the complexity of the rich and varied influences across cultures and time. “History is never closed. There are fluid connections from one space and one history to another.”

Noting that the Met’s curators have a deep sense of responsibility in how they tell the stories of a culture and its objects, Tehrani has designed these galleries, set to open in 2027, to provoke discussion about traditions of collecting, and as he puts it, to explore “how objects are transformed when they enter the museum space as well as their roles in shaping and constructing knowledge.”