Anthony Candido 1924 – 2023

POSTED ON: October 27, 2023

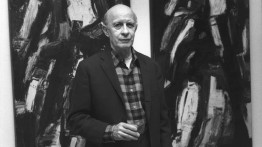

Tony Candido at the opening of his 1993 Houghton Gallery exhibition Tony Candido: Paintings, Drawings 1955-1993.*

It is with great sadness that the School of Architecture announces the death of former faculty member Anthony Candido, who taught at The Cooper Union for over forty years. During those decades, Tony taught numerous design studios and seminars, including thirty-three Design III studios in close collaboration with his colleague and friend, the late Richard Henderson, from the fall of 1983 through the spring of 2000. He retired from teaching in 2015. Prior to his arrival at Cooper Union in 1959, Tony taught architecture at Cornell University; University of California, Berkeley; and The City College of New York.

Tony’s trajectory in the disciplines of architecture and art was singular and significant. He received his Bachelor of Architecture from IIT in 1954 under the directorship of Mies van der Rohe and studied city planning under Ludwig Hilberseimer. He made the first design for Konrad Wachsmann’s Air Force hangar’s longitudinal elevation under Wachsmann’s direct supervision. He was an architectural designer with I.M. Pei from 1954–57, where, among other projects, designed a single support 180-foot diameter steel and glass structure for Roosevelt Field—a first. Tony was also a major contributor to the design of the U.S. Pavilion for Expo ‘70 and he went to Osaka, Japan in 1969 to supervise its construction, before leaving the practice of architecture to focus solely on his work as an artist.

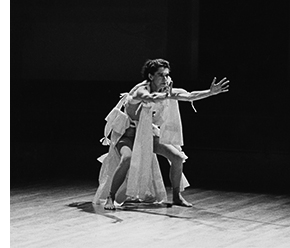

Tony was an accomplished painter—he began working independently in his painting studio in 1957. He and his late wife, the dancer and choreographer Nancy Meehan, were among the first tenants at Westbeth Artists Housing when it opened in 1970. For decades they practiced their respective arts with intensity and passion, and they collaborated often, with Tony designing, making, and sometimes painting visually kinetic and architectonic costumes for Nancy’s works.

Tony’s place in the history of modern art—specifically in New York City—is undeniable, and fellow artists Sol LeWitt and Franz Kline were friends of his early in his career. Their conversations and correspondence focused on the work of their contemporaries. The depth of these exchanges is revealed in a letter from March 15, 1962, when LeWitt wrote to Candido:

There are a couple of shows that seem to have given everyone a boot one way or the other. One is Lichtenstein the other Rosenquist. Lichtenstein at Castelli’s is more in the Johns tradition of the familiar or banal used for shock; he does cartoons but large (4’ x 5’ or so). They have balloons with talk etc. or ads (soap, etc.). They achieve their purpose (of shock) and the show was sold out. They are purposely not “well done” – there is no art in them. I wonder what he’ll do for an encore – that’s his problem.

Tony Candido’s work includes an extensive body of mostly oil but also acrylic paintings, as well as sumi ink brush stroke paintings on handmade papers, in a variety of scales—many of them larger than Tony himself. He was resolute in his convictions about art, especially his own art. He rarely wavered in his thinking. In describing his abstraction paintings, in his publication The Great White Whale is Black, Tony wrote:

For me the brush stroke is the concrete formative element, which in a direct hand-to-mind action plastically activates the space of the painting, through which a reality far greater than the apparent is realized. The technique of brush and ink suits my sensibility. I can, in effect, carve out large spaces with one sweeping stroke. A combination of grace and strength are available within the range. I see a profound meaning and mystery in the stroke. For me, looking into the stroke and seizing its action promotes an alertness and a clearness of mind which is unexplainable, and herein lies the way to unimaginable leaps and transformations.

Tony’s paintings have been exhibited at The Canadian Center for Architecture, Montreal; Galerie de L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Lorient, France; The International Design Forum, Asahikawa, Japan; The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; and the Attitudes Gallery, Denver. He also exhibited his work at various New York galleries, including Area Gallery, Betty Parsons Gallery, The Painting Center, the Arthur A. Houghton Jr. Gallery of The Cooper Union, the Philippe Briet Gallery, 101 Wooster DNC Exhibition Space, Spectrum Gallery, St. Mark’s Church on the Bowery, and Westbeth Gallery.

Two monographs of Tony’s work, each associated with an exhibition, were published by The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture: Tony Candido: Paintings/Drawings 1956 (1993), and The Great White Whale is Black (2014). His artwork and writing are also included in the publications New World Writings #13, 1958; Loka II, 1976; Education of an Architect, 1988; and Casabella, October 1997. He was nominated for a Chrysler Award in 2002. A collection of his work, photographs, and papers was acquired by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art in 2019.

In The Great White Whale is Black, Tony wrote about teaching:

Training in architecture, if it’s good, leads to the ability to tackle something new without fear. Because an architect, if he or she’s not strictly a pencil sketch artist, knows how to build. I’m a proponent of a strong structural background. In fact, to me, teaching is a very simple job. What do you do teaching architecture? You impart a certain amount of information, trying to increase the students’ knowledge while eliciting creative work. You’re teaching them something and they’re in the process of doing something creative. It’s a creative process—a very unique education. Architects can, as I tell the students, help. And how can they help? By making good buildings. You don’t have to be Frank Lloyd Wright, but just do a good job. That was Mies’ approach; he taught people to be good architects. I’m approaching it from a different direction, and in the seminar especially, I want to crack ice. I want the students to get into areas that they don’t get to in the studio. That’s how I work. I make drawings for possibilities.

Anthony Nicholas Candido was born in New York City on September 5, 1924. A son of The Bronx, he observed the construction of the George Washington Bridge as a young boy. His contemplation of and visions for large-scale megastructures were lifelong considerations, and clearly present in the 2010 Cooper Union exhibition Tony Candido: The Great White Whale is Black, as well as in his Urban Farm design studio prompt and resulting student work. During World War II Tony served as a B-17 “Flying Fortress” bomber pilot in the U.S. Air Force. He was stationed in England, flew numerous missions, and was discharged from the military after he turned 21.

Tony recently celebrated his 99th birthday. He was a force of nature, a commanding presence with an intense zest for life. The sound of his powerful voice was unmistakable and unforgettable. As an educator, he had an impact on generations of architects. He is beloved by his former students, colleagues, members of the Nancy Meehan Dance Company, and beyond. He will be missed by many.

Steven Hillyer, Director

The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture Archive

*Photo credits: Liselot van der Heijden, Johan Elbers, Liselot van der Heijden, Anita Kan, Barb Choit