Ariana Revilla

This slideshow is part of: 2013–2014 Fellowship Recipients

With the assistance of the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship, I traveled to Socorro County, New Mexico intent on constructing photographic installations receptive to a latent narrative buried by the vastness and quiescence of the desert. My project began with the study of four sites: (1) the location of the ‘Lonnie Zamora Incident,’ a close encounter of the third kind that scarred the earth with physical evidence, (2) the Very Large Baseline Array, an observatory and hub of astronomical research comprised of a radio telescopic network infrastructure covering a territory of over 600 square miles, (3) the Trinity test site, the birthplace of nuclear warfare and the detonation site of the first ever atomic bomb, and (4) Fort Stanton, a now abandoned military fort where Japanese-‐Americans were interned during World War II. The proximity of these events within Socorro County raised questions regarding the role of desert(ed) space in the construction of cultural and historical narratives. I found these events to be inexplicably related, codependent on each other and on the place they occupied, yet they lacked any cognizant delineation in Socorro County or memorial in significant form. Like ruins of past architectures, the sites of these events are untouched but in the New Mexican desert this “preservation” translates to vacant spaces. My travels broadened the scope of my research to address the paradoxical spatial condition of the desert : a place of ambient histories, a complex layering of experiences that are fostered by desolation and simultaneously forgotten by it.

The desert terrain invites the extraordinary and experimental, yet these stories remain latent, succumbing to the primary connotations of expanse and nothingness associated with this landscape. My thesis argues a mnemonic link between the place of the observatory and the space that it observes. The transcription of the night sky in our atmosphere is a photograph that predates the camera. I mean this literally, examining the etymology of the word photograph – from photos (ϕοτοσ) light, and graphos (γραοσ), writing, delineation, or painting. Because of the time it takes for the image of the night sky to travel here by light, (the closest star being 4 light-years away), the night sky we look at is a photograph of the past, an extinct landscape. Like the flatness of the desert, the night sky, as we see it, is a compression of dimensions. It is this photographic likeness that finds parallel in the desert landscape. The desert’s signification, reduced to its two-dimensional ground plane, excludes the depth of time and memory contained by this “empty” space. Generally, the desert lacks close observation, memorial or record. Through the means of astronomic and inherently photographic tools, the stories within the desert can be revealed and remembered.

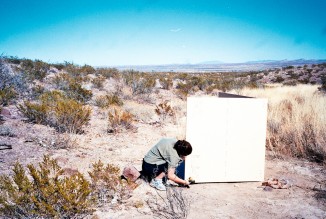

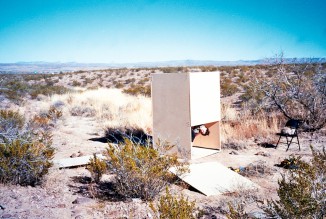

The timing of my travels, in January, midway through the thesis year, provided the opportunity to design and build full-scale installations on site. These small-scale observatories served to mark and memorialize forgotten events in Socorro County through photographic devices. An observatory of autonomous parts, these installations created their own “constellation” across a vast and boundless area, acknowledging and correlating notable sites, and illuminating a sphere of historical interest. I viewed these constructions as a very fitting midpoint for my thesis. Their completion, materialized full scale on site, concluded my introductory exercise on photographic spaces. Having been able to physically manifest these programmatic combinations of observatory—memorials allowed for meditation and analysis on a fulfilled exercise and of a theoretic trajectory as I moved forward with my project.