2013–2014 Fellowship Recipients

Eduardo A. Alfonso | Sectarian Communities, NY

Derrick Benson | National Radio Quiet Zone, WV / VA / MD

Lorenzo Bertolotto | L’Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy

Ten-Li Guh | Paterson, NJ

Morgan Gostwyck Lewis | Paris, France

Che D. Perez | St. George’s, Grenada; Port of Spain, Trinidad

Ariana C. Revilla | Socorro County, NM

Projects

-

Ariana Revilla

-

Che Perez

-

Morgan Lewis

-

Ten-Li Guh

-

Lorenzo Bertolotto

-

Derrick Benson

-

Eduardo Alfonso

Back

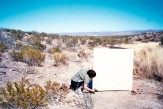

Ariana Revilla

With the assistance of the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship, I traveled to Socorro County, New Mexico intent on constructing photographic installations receptive to a latent narrative buried by the vastness and quiescence of the desert. My project began with the study of four sites: (1) the location of the ‘Lonnie Zamora Incident,’ a close encounter of the third kind that scarred the earth with physical evidence, (2) the Very Large Baseline Array, an observatory and hub of astronomical research comprised of a radio telescopic network infrastructure covering a territory of over 600 square miles, (3) the Trinity test site, the birthplace of nuclear warfare and the detonation site of the first ever atomic bomb, and (4) Fort Stanton, a now abandoned military fort where Japanese-‐Americans were interned during World War II. The proximity of these events within Socorro County raised questions regarding the role of desert(ed) space in the construction of cultural and historical narratives. I found these events to be inexplicably related, codependent on each other and on the place they occupied, yet they lacked any cognizant delineation in Socorro County or memorial in significant form. Like ruins of past architectures, the sites of these events are untouched but in the New Mexican desert this “preservation” translates to vacant spaces. My travels broadened the scope of my research to address the paradoxical spatial condition of the desert : a place of ambient histories, a complex layering of experiences that are fostered by desolation and simultaneously forgotten by it.

The desert terrain invites the extraordinary and experimental, yet these stories remain latent, succumbing to the primary connotations of expanse and nothingness associated with this landscape. My thesis argues a mnemonic link between the place of the observatory and the space that it observes. The transcription of the night sky in our atmosphere is a photograph that predates the camera. I mean this literally, examining the etymology of the word photograph – from photos (ϕοτοσ) light, and graphos (γραοσ), writing, delineation, or painting. Because of the time it takes for the image of the night sky to travel here by light, (the closest star being 4 light-years away), the night sky we look at is a photograph of the past, an extinct landscape. Like the flatness of the desert, the night sky, as we see it, is a compression of dimensions. It is this photographic likeness that finds parallel in the desert landscape. The desert’s signification, reduced to its two-dimensional ground plane, excludes the depth of time and memory contained by this “empty” space. Generally, the desert lacks close observation, memorial or record. Through the means of astronomic and inherently photographic tools, the stories within the desert can be revealed and remembered.

The timing of my travels, in January, midway through the thesis year, provided the opportunity to design and build full-scale installations on site. These small-scale observatories served to mark and memorialize forgotten events in Socorro County through photographic devices. An observatory of autonomous parts, these installations created their own “constellation” across a vast and boundless area, acknowledging and correlating notable sites, and illuminating a sphere of historical interest. I viewed these constructions as a very fitting midpoint for my thesis. Their completion, materialized full scale on site, concluded my introductory exercise on photographic spaces. Having been able to physically manifest these programmatic combinations of observatory—memorials allowed for meditation and analysis on a fulfilled exercise and of a theoretic trajectory as I moved forward with my project.

Che Perez

I began the research for my thesis thinking about how architecture can encode a cultural identity into the built environment, and more specifically, into the condition of former colonialist cities in Caribbean nations, mindful of the fact that the people who currently live in those cities inhabit remnants of the colonial era. I chose to travel to two cities, Port of Spain in Trinidad and St. George’s in Grenada, because they are emblematic in scale of many other cities in the Caribbean. In my travels I understood more clearly a thriving urban condition of cultural identity in the Carnivals there, with which an architectural dialogue could be opened.

I examined the Carnival because for Caribbean people it represents a form of cultural identity. The costumes, music, food and general atmosphere of collective euphoria is as tangible as any monument, emblem or flag. In Trinidad I interviewed a number of Carnival participants – musicians, calypsonians, costume designers and artists who were in the midst of preparations for the Carnival that would take place two months later. They understood their roles as competitive players in the projection and propulsions of the annual festival, but on a more fundamental level, they were together working on the Carnival as a collective, cultural and urban project.

Then I turned my attention to the actual urban form. In Port of Spain I engaged in conversations with architects, writers and urban dwellers. I recorded a number of insights about the city as it is, its potential and also, interestingly, its past potentials – unrealized plans for the city that were speculated upon during the independence movement. It was brought up in many conversations that too much of recent urban development has been skewed towards satisfying purely political and economic forces. Similarly, in St. George’s, plans are currently in deliberation to privatize the bay around which the city is built for yachting, cruise ship and marina purposes as economic development takes precedent.

It was crucial for me to be able to visit the archives of these cities to see firsthand unpublished historical maps and speculative plans of the cities dating from the 1500s to the present. The director of the archive was in the process of writing a book that depicted the history of the city when it was ruled by the French in the 17th and 18th century, prior to the British. In a walking tour of St. George’s with the director and a local architect, we engaged in a conversation about the future of the Caribbean city and the important role architecture plays in shaping that vision.

There are many more interesting and crucial experiences that I was lucky to have had on this trip. I found that an architectural project for the Caribbean region would need to address some of the issues I learned about and that the Carnival provided a lens through which one can see the Caribbean city in a different light and act architecturally within it with a cultural sensitivity.

Morgan Lewis

Tracing Follies

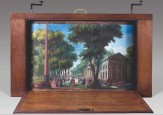

“To put together into one garden all times and all places” was the desire of the 18th Century Landscape Architect Louis Carmontelle when he set out on his most ambitious project, the Parc Monceau. Its chaotic and disjointed plan shows an assemblage of diverse fragmented follies connected by the loosest and most meandering of paths. When I first came across the plan in a book of European gardens it seemed impossible to understand its spatial hierarchy, or the purpose of this strange collection of disparate elements. There was something compelling about a composition that appeared so evasive, and so different from the garden-as-room plans I had been looking at up to that point in my thesis.

Although I went to Paris to explore the entire works of Carmontelle, it was walking in the garden at Monceau that was foremost in my mind. The garden, comprised a network of follies in a miniature landscape, is now enclosed by the majestic urban plan of Paris. The follies were of unclassifiable age and placed in unintelligible order. Roman temples were to be found next to Gothic arches and Egyptian tombs. Its creator, Carmontelle, stated that he designed this collection of pastiche fragments as “a tour of the world and its history.” This was not an effort to achieve an encyclopedic comprehension but its reverse; to achieve an environment that was “simply a fantasy.” The ultimate purpose of this disorienting fantasy was to become the stage set for the most licentious and pleasurable of acts of court. Here, in the decade before the Revolution, the French aristocracy played and courted in a setting that shockingly transgressed conventional boundaries of time, taste and the borders between the natural and the architectural. Its irrational, spasmodic plan sought to avoid any focus or aim beyond its own satisfying gratification.

I visited a number of other historic gardens, landscapes and archives during my nine days in Paris, from the 17th century Jardin de Luxembourg to the forests of Fontainebleau – brought to fame by the Impressionists – to the Parc de la Villette of the 1980s. The experience had a wide impact on the development of my thesis, which includes the development of a temporary garden in South London as part of a hypothetical intervention into a speculative master plan. Prior to receiving the William Cooper Mack Fellowship I had been focused primarily on the particular garden that had been on my site. The trip opened me up to a French tradition that was new to me – the garden as a fantasy landscape that could be enjoyed through theatrical play. Furthermore it showed how a fragmented ruined architecture could speak of a past that has been irrevocably lost as well as how those fragments could play a critical role as an element in a new composition.

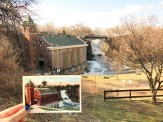

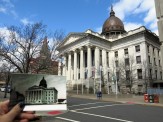

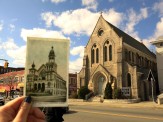

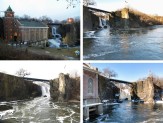

Ten-Li Guh

William Carlos Williams led me to Paterson. I was immediately drawn to the opening lines of his long poem named after the city: “a reply to Greek and Latin with the bare hands…by multiplication, a reduction to one…a dispersal and a metamorphosis.” While describing his own poem as a “failing experiment,” Williams’ Paterson was an attempt to redeem the failure of the American language through an intimate study of a failed American city.

The first planned industrial city of America, Paterson, New Jersey is now a city debilitated by the abandonment of its founding identity. Disparate relics populate the urban fabric as longstanding testaments to the city’s historic failure. The anchor of Paterson, however, still stands today, just as it had some 13,000 years ago since the end of the last ice age. The “lucky burden” of the Great Falls and the envisioned potential to harness its waterpower preordained the very conception of the city.

I made many trips to Paterson, always equipped with a camera and the Williams poem. I would arrive by train and roam the city by foot. I relied on Paterson as a textural map, allowing me to make better sense of my contact with the place.

Drawing from Williams’ allusion to The Unicorn Tapestries, I appropriated the image of “The Unicorn in Captivity” and used this as a key to recontextualize my reading of Paterson. After identifying particular vertical towers within the city that were emblematic of its former glory, I likened them to the stakes of the fence that encloses the unicorn. The Great Falls, whose stature had been exceeded by its surrounding cityscape, became the symbolic unicorn. On my fifth and final trip to Paterson, I embarked on a pilgrimage that I had devised for the city. Positioning myself in front of each architectural monument, I held a historic image in my hand, layering it with the present in the background. This photo series would become representative of my role as both interceptor and mediator of the city.

As a result of my visits, the kind of architecture that I envision for Paterson will be intrinsically tied to the multiple narratives that I have encountered, namely, those derived from Williams’s poem, the historical city, its current state of ruin and the geological formation of the rift in the rock. In its multiple forms, the new monuments will occupy the site of the falls and bleed into the urban fabric, at once memorializing the inherited histories while also transforming the spatial and experiential impression of the place.

Lorenzo Bertolotto

My thesis addresses the reconstruction of the city of L’Aquila in the Abruzzo Region in Southern Italy. The city was struck by an earthquake in 2009 that completely devastated the historic downtown and has gained international attention for the scandals that have affected the city during reconstruction. The William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship granted me the opportunity to travel the city to better understand its current condition.

Little has been done since the earthquake five years ago and the failed reconstruction that has rendered the city center a ghost town for the past five years; it remains an abandoned labyrinth of locked doors and inaccessible buildings. The state of desolation can only be experienced by walking its streets. The downtown is still partly fenced off and under the control of the military. No one is allowed to access the historic districts by car without authorization, and some areas are completely off-limits.

I walked around L’Aquila with public figures Emanuele Curci and Alfredo Munzi to gain a sense of place that has now vanished, though it was when exploring the streets alone that I really understood the sense of loneliness that affects the city. I wandered through the streets without meeting anyone, only accompanied by the background noises of the few construction sites. By night the city is even more deserted. The construction workers that provide some vitality and noise are gone, leaving behind complete isolation. Many of the streets do not have public lighting, and other people can only be found in a small area.

As the administrator of the organization Policentrica Onlus, Emanuele invited me to join one of their meetings which gave me a broader understanding of local politics, the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, the military occupation, the struggle of the reconstruction and the scandals that have been affecting the city since the earthquake. Policentrica has been working towards a reconstruction of communal structures that have been destroyed along with the architecture. The articulation of the architectural urban space – the alternation of solids and voids, of piazzas, streets, avenues, coste, alleys, and arches – fostered most of the social interactions between Aquilani.

Alfredo Munzi showed me the surroundings of L’Aquila, specifically the infamous C.A.S.E. and M.A.P. projects. These projects, built by the Italian government to provide housing to the affected population, became known as the symbol of wastefulness and of the crooked administration. They were often built by companies that provided kickbacks to the local government in order to be assigned contracts. This made the construction very expensive and, at the same time, of very low quality. After five years, the structures are already falling apart and lack any basic service or civic space.

During my week in L’Aquila, yet another scandal broke out, involving the Vice-Mayor and other local administrators, who had also received kickbacks from construction companies and scaffolding contractors. This scandal further explained the delays in the reconstruction: the longer the rebuilding effort lasts, the more the contractors and those in power benefit. The scaffolding, rather than a temporary support for the city, has become a crutch that is delaying its redevelopment.

Derrick Benson

My project explores the conditions in which secrets are generated and exposed, kept and disclosed; it questions the delineation of boundaries between those who know and those who don't while investigating systems of inclusion and exclusion conditioned by the secret, and the correspondent knowing and unknowing publics these systems determine. The project proposes a role for architecture in both elaborating and exposing conditions of secrecy, as well as in the fabrication of the realities that these conditions mask.

Developing within a collection of redacted documents - documents released under the guise of shared and free information, but documents, which through a process of erasure, elimination, and obscuration, reveal little in the way of tangible fact - the project operates through a fragmentary knowledge. Paranoia and conspiracy theorizing take shape, and a reality of UFOs, telepathy, mind control, and government surveillance is constructed.

As an extension of our contemporary information age, the documents hint at the promise of information made public – the promise of knowledge through accessibility and extended communications networks – but they disclose a reality of secrecy and mistrust and suggest processes of manipulation underlying the manufacture of public knowledge. And the drive to know – presupposed by the documents' release and inherent to and intensified by new media – elaborates a system of paranoia and conspiratorial thinking, a system in which more information is always available, and knowledge awaits if only it can be uncovered or disclosed.

The National Radio Quiet Zone (NRQZ), covering approximately 13,000 square miles of land in West Virginia and Virginia, uniquely frames these multiple anxieties of our contemporary information age. Designated as such in 1958 by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the NRQZ is characterized by restrictions on radio and wireless transmission signals - restrictions that effectively disconnect the zone from broader communications networks while serving to protect the operations of two highly connected facilities around which the zone is centered. The first, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Green Bank, WV, is home to a variety of radio telescopes that provide a means of engaging in a wide array of astronomical inquiry, ranging from gravitational radiation and planet composition, to star and galaxy formation, while ultimately probing the very origins of life. The second facility, the Naval Information Operations Command (NIOC) in Sugar Grove, WV, is a military base with a history rooted in Cold War intelligence gathering and current ties to the National Security Agency (NSA), assisting in the interception and de-encryption of communications entering the eastern United States as part of a program codenamed ECHELON.

The NRQZ is disconnected through its hyper-connectivity, existing simultaneously apart from and in exchange with the world outside it – blocked from but actively engaged in broader communications networks. The zone contrasts the uninformed with the highly informed, framing a conversation about information exchange in relation to notions of secrecy and paranoia. This is elaborated by the efforts of the two facilities within the zone, one seeking a knowledge unknowable through its astronomical research and one operating through knowledge withheld to conceal its surveillance program. So, in setting out to visit the NRQZ, I aimed to experience and document the disconnection and quietude that enables the connectivity of the zone, while uncovering the traces of paranoia latent within it.

Eduardo Alfonso

“It was the intensity of their vision coupled with their isolation in the wilderness, that caused them one and all to place on the canvas veritable capsules, surrounded by a line of color, to hold them off from a world which was most about them.” — William Carlos Williams, Painting in the American Grain

Rather than continuing the rhetoric of urban expansion by proposing another master plan, this project takes the form of a retreat. A retreat is a line: it holds things in and out. It moves away from one mode towards another, but does not try to define a new orthodoxy. Its inhabitation is temporary and its forms are fragmentary. It acknowledges that spatial scenarios within the city that are entropic have the potential to provide a scene in which to redefine inhabitation. This scenario within the contemporary city can be reframed as a (new form of) wilderness, in which inhabitation and social configuration can also become entropic.

Exploration of these themes began with studies of religious societies and pioneering efforts that existed along the shifting border of the United States. These societies, which included The Shakers, The Moravians, The Rappites, The Owenites and The True Perfectionists, were investigated not for their theological and eschatological systems as such, but rather for their desire to invert architectural typologies and hierarchies in order to seek new possibilities within the logic of domestic space. In these communitarian societies, notions of public versus private, and individual versus common are in a continuous process of redefinition. This redefinition could only take place within the logic of the wilderness. This research culminated in a visit to multiple historic sites, which had been inhabited by these radical groups.