Engineering with a Conscience

POSTED ON: December 12, 2019

This fall, Sam Keene, an associate professor of electrical engineering, is co-teaching a course called Hiding from the Eyes of the City with Benjamin Aranda, an assistant professor of architecture. The new seminar delves into the politics and social impact of advances in surveillance technologies. “We can imagine an arms race where facial-recognition technology is improving and people’s methods to defeat it are improving,” says Keene. “We’re postulating this scenario where only the wealthy can avoid surveillance, and there’s a total surveillance state for everyone else. How is that an equitable society? What does that mean for public spaces if only certain people can move through them completely undetected while everyone else has all of their movements tracked?”

The course is only one of the many avenues available to Cooper students for grappling with the ethics of new technology. And it’s not just for those studying engineering; essential to the discussion is interdisciplinarity. “The issue with new technology is that it’s not just about science, engineering, and mathematics,” says Birgitte Andersen, CEO of the London-based think tank Big Innovation Centre. “It’s really about complex problem solving. It’s about creativity, it’s about people management, it’s about emotional intelligence.”

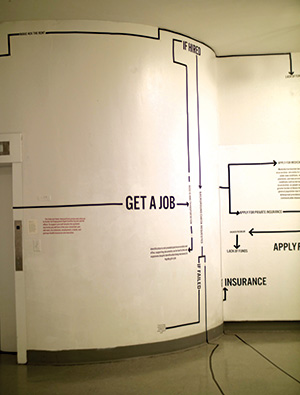

Andersen was one of a panel of experts who came to Cooper last February to discuss the future of the workforce: Are robots going to take our jobs? Will new technologies create more economic opportunity, or drive unemployment and inequality? How should institutions of higher education prepare students to lead in a workplace transformed by automation? Raising such questions is the goal of Mark A. Vasquez ME’88, program manager for the TechEthics program of IEEE, the world’s largest professional organization advancing technology for humanity. They co-sponsored the panel, which is part of the larger vision that Barry Shoop, dean of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering, has brought to the school since joining it last winter: giving Cooper students new learning opportunities in the ethics of technology.

Like Andersen, Shoop believes that preparing students to work with emerging technologies requires teaching them how to engage with problems from outside perspectives. “I think it’s important you have these discussions across disciplines,” he says. “As an engineer, I have a certain set of ethics, but when you bring a philosopher into the equation, that is a much richer description, a much richer conversation about ethics and how it applies to technology.” While job prospects in fields such as robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), data science, and machine learning have exploded in recent years, educators and employers alike are seeing the importance of combining STEM training with the “soft skills” traditionally associated with liberal arts and humanities majors.

Granted, ethics has always been an important part of engineering, as Shoop is quick to point out. Codes of ethics are part of both the accreditation process for engineering schools and the membership requirements for professional societies such as IEEE. So what’s changed in recent years? “I think from my perspective what has really brought things to the forefront is the autonomy we’re beginning to see that results from new technology,” he says. “What I’ve seen in ethics has surprised me a little bit because when you start building these autonomous systems, there’s much more than just the question of right and wrong in terms of what the system is doing.” One particularly nuanced area of ethical concern, he says, is the problem of unintended and implicit bias, which can influence the decisions made by algorithms.

Starting this semester, the school of engineering will offer an official minor in computer science, a field where the dangers of bias are especially pronounced. As the application of big data and machine learning becomes more pervasive, ethicists are drawing attention to unintended racial and social biases that can creep into statistical models, which hold serious consequences for everything from screening job applications to assessing insurance risks to policing to predicting recidivism—all areas where decision-making is increasingly being delegated to algorithms. Shoop sees problems such as these motivating a shift to rethink and expand the role of the engineer.

“When I came out of Penn State in 1980, an engineer was an engineer,” he says. “Now, employers are asking engineers to have a conscience, to understand more about the ethical considerations of what they’re doing and the broader environment.” But what does broadening engineering education to incorporate more of the humanities mean for a profession largely organized around deep technical specialization?

“In part, IEEE TechEthics aims to help bridge the gap between those who are deeply immersed in technology and those who are part of the conversation but are not necessarily technologists themselves,” says Vasquez, who is also a member of the Cooper Union Alumni Council. This extended audience includes stakeholders such as philosophers, sociologists, entrepreneurs, policy-makers, and the general public. “From a professional perspective, we’re interested in bringing the dialogue forward so we can have a very comprehensive and sound conversation on a variety of technology areas. Technologists are always at the core of the discussion. By adding multiple voices to the conversation, we seek to balance the misinformation and sensationalized manner in which technology information is sometimes delivered.”

The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems is another effort launched as part of IEEE’s mission of advancing technology for humanity. The Global Initiative promotes dialogue among practitioners about the ethics of AI and other decision-making technologies. This initiative has published Ethically Aligned Design, a set of crowdsourced recommendations for industry compliance standards and best practices; its second edition places greater emphasis on understanding global perspectives and cultural differences. “IEEE publishing its second version of Ethically Aligned Design has really brought ethics forward in the industry,” notes Shoop, who served as the professional organization’s president and CEO in 2016. IEEE TechEthics has similarly championed efforts to diversify represented viewpoints, with panelists from across the globe included as part of their regularly scheduled online and in-person events, where various challenges in the technology ethics space are discussed.

Turning to his alma mater to co-sponsor events, Vasquez says, is a no-brainer. “Cooper is a place where people come for public discourse, and the kinds of topics we’re talking about lend themselves to engaging with the public.” With alumnus Stephen Welby ChE’87 serving as IEEE’s current executive director and chief operating officer, the connection to Cooper has been a fruitful one lately. Last May, Cooper hosted a talk focused on AI, ethics, and healthcare that featured the executive director of the IEEE Global Initiative. Vasquez is also working with the school of engineering to plan additional IEEE TechEthics co-sponsored panel discussions in the 2019–2020 academic year. The second session took place in November and focused on autonomous vehicles and self-driving cars.

Keene, the co-teacher of Hiding from the Eyes of the City, has been working for several semesters to bring engineers, architects, and artists together in the classroom. Previously, he taught Machine Learning and Art, which he co-taught with artist and writer Ingrid Burrington, and Data Science Projects for the Social Good, co-taught with Will Shapiro AR’11, the founder and chief data scientist of a company that uses AI to understand cities, and later with Taylor Woods A’15, a designer and illustrator.

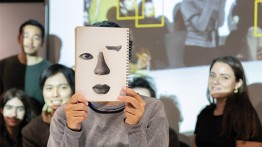

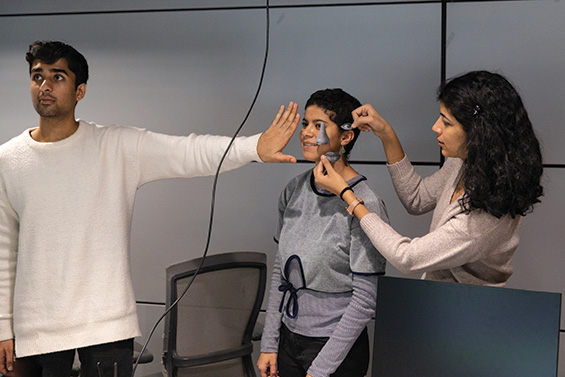

The goal of Keene’s current course will be to build and present an interactive demo at the Shenzhen 2019 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/ Architecture in China, inviting participants to input photos of themselves into a database and try different methods of concealing themselves from the facial-recognition technology. “If you put a mask over your face, you might be invisible to the system, but from a human perspective it will be obvious that you’re trying to avoid it. If you’re more subtle, if you just have a pin or a texture or something that’s less observable to you and me but that makes you invisible to the system, that is extremely valuable.” The class includes a group of electrical engineering students, who are building the facial-recognition technology, and a group of architects, who are designing and fabricating the exhibit. “You’ve got engineers and architects in the same classroom talking about this technology, asking what are the political ramifications, how do you design an exhibit around it,” Keene says.

One unusual aspect of the project is that, although it raises questions about surveillance and government overreach, it cannot explicitly reference the current political situations in Hong Kong and China. A ban on wearing face masks in public in Hong Kong, enacted under an emergency powers law, has just recently exacerbated the semiautonomous territory’s ongoing political unrest. “We have to submit the project to a Chinese cultural committee, which is essentially a censorship board,” he says. “So even though we’re accepted to this biennial, we still don’t know if it’s going to happen, if it’ll get approved.”

From Keene’s perspective, thinking about the ethics of technology means going beyond liability and industry compliance frameworks and bringing it into the context of contemporary issues and the tangible impact that engineering has on the world. “In my machine learning class especially, we spend time on social problems and unintended consequences related to communications and networks. When they first envisioned the Internet, for example, it was designed as a network of open and trusted computers working together benevolently. We talk about how incorrect their assumptions were, and now all those things are built into the architecture of the Internet, which is why security is such a problem now. It was never fundamentally built to be secure.” Ultimately, the question Keene wants engineering students to ask in their design choices is not just “How do we make that?” but “Should we make that?”

It’s a question that was often raised in the Machine Learning and Art course. Co-teaching with an instructor from outside his discipline, Keene says, helped change his own perspective, and in turn he saw engineering students thinking more critically about design choices. As a result of that experience, Keene asked Burrington to teach Ethics of Computer Science, a new course being offered this semester that challenges students to explore the historical and ethical dimensions of living in a world governed by computers.

Keene hopes to create additional opportunities this spring for both the Cooper community and the general public to learn about emerging technologies. He and Taylor Woods want to host a series of talks by guest speakers with expertise in data science, data visualization, design, ethics, and other topics related to their Data Science Projects for the Social Good course. They received funding for the series last semester through the new Cooper Union Grant Program.

Similar pushes for cross-disciplinary conversations about technology have come both from outside the school of engineering and from the students themselves. “A group of students approached me and asked if I would teach a course on the ethics of AI,” says Sohnya Sayres, an associate professor of humanities. As a result, Sayres is teaching a course this semester called Artificial Intelligence and Ethics. But rather than focusing solely on applied ethics, Sayres wants students to ask bigger, more-speculative questions about the nature of intelligence, automation, and technology.

“Technology always presents itself as solving all our problems,” says Sayres. But of course, it also raises new problems—and questions—of its own. “What do we mean when we talk about human or artificial intelligence? What do we mean by a just world?” she asks.

For the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS), all this buzz about the ethics of emerging technologies comes at a time of renewed focus on the role of the curriculum in preparing students as critical thinkers and civic-minded practitioners. Elevating HSS as an integral part of professional education at Cooper is one of the main charges of the Council on Shared Learning, a committee of students, faculty, and administrative staff members that was formed last semester, partly in response to various student groups voicing concerns about diversity and decolonization within the academic community. Anne Griffin, professor and newly appointed acting dean of HSS, believes the time has come to enrich the curriculum with courses that draw discourse and knowledge from across disciplines and traditions.

“I would like to see HSS faculty take a greater role in interfaculty exchange and collaboration and in developing intersectional courses,” she says. Automation technologies are one of the areas where, she says, there is the necessity and opportunity for exchange. “We talk about technology and society as if they are two different things, but there are so many ways that they intersect—socially, politically, physically. There is room for generalists because we need to increase our generalized knowledge as the world becomes more technological.” A major part of that, she adds, is making room for serendipity. “There needs to be surprise in the curriculum. Students need to be surprised, to learn something they might not otherwise have had the chance to learn.”

In Griffin’s view, despite its professional orientation, Cooper provides fertile ground for experimentation. “Such a small school makes it possible to have these conversations between engineering and humanities. We each have our specializations, but we are not so rigid that we can’t stray.”