Thesis Year Snapshots 2018: Architecture

POSTED ON: May 4, 2018

This first installment of our annual senior snapshots focuses on soon-to-be graduates of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. The three students featured below—Yaoyi Fan, Rick Farin, and Athena Unroe—will be among the last students to have been taught by the late Professor Diane Lewis AR'76. All three found her fourth-year studio to be deeply formative, a moment in their careers at Cooper that notably shifted their perspectives about how they viewed architecture. Below, each of them muses on their undergraduate years, their thesis projects, and what they now believe architecture can do.

In ninth grade, Yaoyi Fan, an artist since childhood, wanted to learn more about the field of architecture. She headed to a local newsstand in her city of Zhu Hai in southwest China and started leafing through a magazine she’d never noticed before called A Go, a Chinese-English architecture journal. As it happened, that issue was completely dedicated to The Cooper Union’s New Academic Building, its design and construction as well as a description of the school’s history, its reputation as a highly selective institution with no tuition and its dedication to rigor and creativity.

In ninth grade, Yaoyi Fan, an artist since childhood, wanted to learn more about the field of architecture. She headed to a local newsstand in her city of Zhu Hai in southwest China and started leafing through a magazine she’d never noticed before called A Go, a Chinese-English architecture journal. As it happened, that issue was completely dedicated to The Cooper Union’s New Academic Building, its design and construction as well as a description of the school’s history, its reputation as a highly selective institution with no tuition and its dedication to rigor and creativity.

She bought the magazine, then went home and announced to her mother that she planned to attend Cooper. Her mother’s dispassionate reaction—more or less a version of “Well, good luck with that”—didn’t discourage Yaoyi, who decided that she’d have a better chance of getting in if she attended an American high school. The resourceful teen, who says her grades weren’t particularly strong at the time, began to apply to American high schools. By her junior year she was living with an American family in Fall River, Massachusetts and attending Bishop Connolly High School, all while still setting her sites on Cooper. And, as planned, she gained admission, arriving in New York for the first time in September 2013 at the beginning of her first semester.

After that first semester, she says, “Everything I saw in the world looked different.”

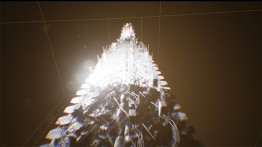

For starters, she was thrilled with Professor David Gersten’s first-year studio for which she and a group of her classmates built a 8’ x 6’ model of the Great Hall. “We were a very diverse group with older students too. And the upperclassmen were amazing—we learned a lot from them.” The late Diane Lewis figured prominently in Yaoyi’s education as she did for others graduating this year. Yaoyi recalls Professor Lewis asking her fourth-year studio, “Does anyone know the shape of hell?” and drawing a sketch of the inferno that she showed to Yaoyi while explaining who inhabited which circle. A year later, Yaoyi found Botticelli’s illustration of The Inferno, a set of exquisite drawings that show figures—Dante and Virgil, for instance—moving through space at different points in time within the same drawing. The artist’s strategy influenced Yaoyi’s thesis, in which she used cameras and Photoshop to create images analogous to Botticelli’s. “The conical shape of hell represents the density of suffering,” says Yaoyi. “And it’s the people’s perception of hell—repeating the same movements in a smaller and smaller space—that creates the cone.”

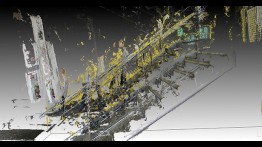

As a child, Yaoyi had wanted to be a dancer, and in some ways, her thesis project resurrects that love. In order to convey the notion of architecture as the result of movement, she took multiple images of people moving through space using as many as 50 cameras that captured the subject from multiple vantage points. Using that data, she created exceptionally beautiful drawings that not only charted the person’s movement, but also recorded the ways that architectural objects appear to shift from the subject’s perspective. So in her drawings elements such as a column, a symbol of stability and stasis, appears to be as vulnerable and mutable as any living creature moving through a space.

Her thesis also included drawings in which the New York City subway system acted as the stand-in for hell. She proposed a series of designs that created different paths of circulation for people to arrive and depart while offering public space for people to rest, gather, or observe the great mobility of their fellow citizens.

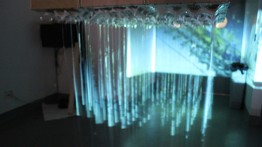

In addition to those drawings, her thesis includes a sculpture made by pouring sugar through a plastic frame of extruded funnels—echoing the shape of Botticelli's hell. As the sugar runs through the frame, Yaoyi projects videos she made of her drawings onto the light-catching crystals.

Yaoyi is a teacher in the Saturday STEM program as well as an assistant to Professor Pablo Lorenzo Eiroa. They are designing and building a giant 3-D printer, two meters in height, that they’re bringing to the Venice Biennale—she’s leaving the night of graduation. She is also part of a team of Cooper students building a model for the upcoming exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art about modernism in Yugoslavia, “Toward a Concrete Utopia.” Afterwards, she will look for a job and may eventually apply to graduate school.

As for her years at Cooper, she says, “The work here is so intense. I see the school as a monastery for learning and I indulged myself. I wanted to learn so much. And I have.”

As a native of Los Angeles, it may be no surprise that Rick Farin has always been immersed in visual culture, especially video games. “I’ve spent months of my life playing video games.” Interested in the relationship between architecture and video games, his thesis project asks an essential 21st century question about digital spaces: “Where are we?” It would be fair to say that for Rick, this is a question whose answers have ramifications both in design and in architecture education. At The Cooper Union, where hand drafting has particular importance in the school’s pedagogy, he has often developed methods to navigate the digital arena in relationship to hand drafting, and he believes digital space-making is as valid a venue for thinking about space as a physical site. “It’s not that I think one is more valid than the other, but I do think that understanding and working with both simultaneously is worth serious consideration. The materials and means by which digital space is constructed are not so different from what is normally considered traditional architectural elements.” He points out that most children play video games daily and are at home with what he calls a “new spatial paradigm.”

As a native of Los Angeles, it may be no surprise that Rick Farin has always been immersed in visual culture, especially video games. “I’ve spent months of my life playing video games.” Interested in the relationship between architecture and video games, his thesis project asks an essential 21st century question about digital spaces: “Where are we?” It would be fair to say that for Rick, this is a question whose answers have ramifications both in design and in architecture education. At The Cooper Union, where hand drafting has particular importance in the school’s pedagogy, he has often developed methods to navigate the digital arena in relationship to hand drafting, and he believes digital space-making is as valid a venue for thinking about space as a physical site. “It’s not that I think one is more valid than the other, but I do think that understanding and working with both simultaneously is worth serious consideration. The materials and means by which digital space is constructed are not so different from what is normally considered traditional architectural elements.” He points out that most children play video games daily and are at home with what he calls a “new spatial paradigm.”

A self-described AP physics nerd, Rick went to an online school until his senior year of high school, where he attended a public arts charter school. Since his education let him learn at his own pace and pursue unique interests, he was able to focus on his creative passions, such as music, gaming, and drawing, but also stay rigorous in his studies, attending community college classes by the time he was in seventh grade. Around the same time, he learned about The Cooper Union and decided it was the right school for him, attracted to the great deal of intellectual independence students are granted. “As far as I was concerned, it was my only real option.”

One of the high points of his Cooper education was during a review in the late Professor Diane Lewis’ fourth-year urbanism studio who said of his work, “Rick, I don’t know what you’re doing here, but you’re some kind of horror architect.”

“After Diane,” he says, “doors were opened in my brain in regards to understanding the relationship that the city has on our collective experience. She could read everything about you through what you’ve made.”

Rick has been writing electronic music for years and performs under the name Eaves, appropriately enough. He has traveled around the world as a performer and has written and produced multiple albums, as well as working with many collaborators, both musicians and visual artists. Rick has often tied his music practice into his architecture work, and when he performs live, he includes a visual component, drawing on his fascination with architecture and gaming as part of the imagery, which is synched to the music being played.

For his thesis project, Rick created a video game that takes players on a journey through their own technology, allowing players to travel along all the sites that the very material of their computer has been mined, refined, manufactured, and recycled too. Part of his thesis asks players to realize their own culpability in the polluting and harmful acts that this production line inflicts, with a deeper objective of trying to provoke what he calls “digital empathy.” During the game, two players interact and engage cooperatively in the game world with unique objects called “kipple,” a term taken from Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. This kipple provides unique insight into the objective aspects of the technology production line, while also acting as means for the two players to communicate with each other nonverbally. The soundtrack acts as a narrative for the game, constructing an emotional affect as the players progress. Sound is the central medium for these narrative explorations. As he puts it, “I’m using audio as a spatial tool.”

“During the game, the world slowly collapses and merges in on itself—imagine as if the players were in a building that was slowly devouring itself. Like you enter the manufacturing plant and you’re suddenly inside a Gothic cathedral, or the gamer’s bedroom, or back in the mine,” Rick says. “It’s tied to an architectural history.”

He points out that he is not in any way advocating for a fully digitized environment for architecture education; far from it. He found the time he spent at Cooper invaluable and believes that applying a Cooper architectural philosophy onto the digital realm is a vital and necessary architectural endeavor. He also believes that the potential of digital architecture is grossly untapped.

Rick wants to apply what he learned at Cooper to the arena of video games, a forum that isn’t traditionally considered part of architecture. He’ll continue his research next fall at SCI-Arc, the well-regarded architecture school in Los Angeles, working on his Master’s degree in what the school calls “Fiction and Entertainment.”

Athena Unroe, a native of Louisville, she has been exploring her city and its river, the Ohio, since adolescence. The Ohio River runs from Pittsburgh to Cairo, Illinois, 981 miles long. At one time it was the most trafficked river in the country, running past quintessential rust belt cities, like Cincinnati, Louisville, and Steubenville, Ohio. With the decline of industry in the United States, the river’s extraordinary infrastructure has largely lain fallow, left to the elements. These structures, which once were so essential to the movement of goods and supplies on the river, are mysterious steel and iron monoliths to recent generations of people who grew up long after industry left the region.

Athena Unroe, a native of Louisville, she has been exploring her city and its river, the Ohio, since adolescence. The Ohio River runs from Pittsburgh to Cairo, Illinois, 981 miles long. At one time it was the most trafficked river in the country, running past quintessential rust belt cities, like Cincinnati, Louisville, and Steubenville, Ohio. With the decline of industry in the United States, the river’s extraordinary infrastructure has largely lain fallow, left to the elements. These structures, which once were so essential to the movement of goods and supplies on the river, are mysterious steel and iron monoliths to recent generations of people who grew up long after industry left the region.

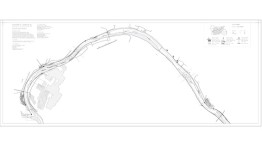

So it comes as little surprise that Athena chose the Ohio and its myriad abandoned piers, bridges, and moorings—all highly advanced technology at the time they were built— as the site for her thesis. “When global markets turned this into a post-industrial region, people moved away from the river,” Athena says. Her thesis proposes a way to get people to return to the river waterfront, and she’s deployed video as a key medium for recording her many research trips in the area. Along the way, she’s discovered just how forgotten some of these towns are. To get to Cairo, Illinois—the once thriving port town where the Ohio and Mississippi rivers meet—she had to take a network of back roads.

Despite the international economic forces that helped create the region, Athena says the infrastructure of the area is “hyper-localized, regionalized,” a reaction to the very particular needs of the river and its attendant towns and cities. “They’re highly flexible spaces, but they’re at a very large scale. What’s needed is a way to make smaller, more human-scaled uses of the space.”

For her thesis, Athena has identified multiple spots along a 350-mile section of the river that she conceives as a new network along the waterway called the Ohio River Passage (ORP). As she states in her thesis abstract, the object is to create, “a set of civic episodic interventions from the densest city [in the region she’s studying], Louisville, Kentucky, to the ruined city, Cairo, Illinois.” Besides using the river as a means to again connect residents of the region, all the sites would have multiple, ever-changing programs as dictated by a community group who determine the activity, its length and its potential participants. Critically, she imagines new structures made from small kits of steel parts alongside the existing steel framework. For instance, she has seen families using a steel pier along one bank of the Ohio as a place to picnic and play sports. So the users themselves determined a new program for the space. Her job as architect would be to provide greater means for such a program to be fully realized, creating small docks as steel armatures that are open enough spatially and can adjust to different types of programs. At another location, she is adapting a field of unused barges to carry passengers from one site, what she calls “a dockland,” to another.

The program she’s imagining at these locations are not an imposition of external cultural groups, but a highlighting of what’s there already: There’s Cave-in-Rock State Park, a 55-foot wide cave created by an 1811 earthquake that served as a hideout for river pirates; a native American burial mound in Evansville, Indiana; and hundreds of intact limestone fossils, some so impressive that they became part of Thomas Jefferson’s collection of natural phenomenon at Monticello.

Studying architecture at Cooper was difficult, she says, especially the first two years, though for the full four years she made a point of visiting the Metropolitan Museum every Sunday. After sophomore year, she made a decision to reorganize her work habits, and rejected the up-all-night-every-night approach she’d initially adopted and so common to architecture school culture.

She’ll take many extraordinary intellectual experiences from Cooper into her professional life, but few as meaningful to her as fourth-year studio with the late Diane Lewis, who Athena says, “was so supportive. It was a studio that let you explore your obsessions.” And studio classes taught her a lot about the dynamics of conversation. “I realized that if I presented at a critique while sitting on a stool, breaking down the typical hierarchy of a line of sitting critics and a student standing.”

After graduating, she’ll study for the New York licensing exams, hoping to complete them over the next two years so that she can start practicing as soon as possible. She’s intent on using her training to build stronger communities and she credits Cooper with that goal. “The school nurtures your sense of identity as an architect so much so that you can be generous, and think about the community you’re working for. The humanities is the basis of our education.”