Senior Snapshots: Architecture 2019

POSTED ON: May 13, 2019

In this second of our annual three-part series featuring some of the year's graduating students we meet Mireya Fabregas, Parker Limon, and Zhenni Zhu, all soon-to-be graduates of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. Each travelled several thousand miles to learn here. They arrived as the first class of the school to ever be obligated to pay part of their own tuition rather then receive the benefit of the full-tuition scholarship granted to every student prior. We asked them about that experience, as well as how they got here, their thesis, and where they will be going next.

It’s possible that Mireya Fabregas was born to be an architect. “Both my parents are architects. My grandfather was an architect, as well as my aunts and uncles. It was something I grew up with,” she says. She grew up in Caracas, Venezuela. “When we travelled, my parents appreciated the cities very differently than others who were not architects. I wanted to have that view on life and to better appreciate construction, buildings, and cities.” She had heard about The Cooper Union from her parents. When she arrived at the school of architecture we featured her as an incoming student. At the time she said she was most looking forward to “doing things I didn’t know I was capable of doing.” She had no idea what she was in for.

It’s possible that Mireya Fabregas was born to be an architect. “Both my parents are architects. My grandfather was an architect, as well as my aunts and uncles. It was something I grew up with,” she says. She grew up in Caracas, Venezuela. “When we travelled, my parents appreciated the cities very differently than others who were not architects. I wanted to have that view on life and to better appreciate construction, buildings, and cities.” She had heard about The Cooper Union from her parents. When she arrived at the school of architecture we featured her as an incoming student. At the time she said she was most looking forward to “doing things I didn’t know I was capable of doing.” She had no idea what she was in for.

That first semester Mireya, along with all the other members of first-year class, participated in what Mireya, Parker, and Zhenni all describe as the most formative studio during their time together: Architectonics, led by David Gersten, co-taught by Wes Rozen and Rikke Jørgensen. The entire class built a six-foot-high scale model of the Foundation Building’s exterior, filled it with their own interpretations of its spaces, and mounted it on a steel frame. Then, taking an already remarkable work even further, they decided to push the model through the streets of Manhattan up to the New York Public Library on 42nd St., and back again.

“That was crazy,” Mireya recalls about the whole enterprise. “It was the first experience we had with building models and working with wood. When the project was presented to us it just seemed impossible. We didn’t have any experience with any of that. Then in four months we were able to build this crazy model. We learned so much about the building. We had to go to rooms and measure them. We got to learn how to use the tools in the shop. But the most important part of that project was that we really got to learn to care for and love our school. I think the love and respect I have for my school comes from that first project. When I talk with my classmates we all agree that one project, that one professor, completely taught us how to love Cooper.”

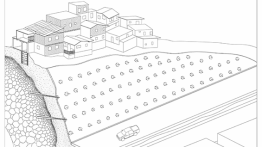

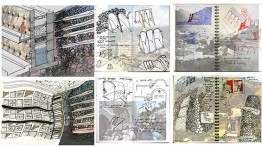

It didn’t end there, of course. Five years later Mireya presented her thesis work, “Redefining Infrastructures to Incorporate Spaces of Exclusion.” Sited in Caracas, the proposal reworks huge retaining walls that were built in response to a series of deadly mudslides in 1999 that killed hundreds in the shantytowns bordering the city. The inches-thick walls are built into the earth, stabilizing the ground under the shantytowns. “But they are strictly designed as an engineering solution,” Mireya says. “So my thesis proposes the potential for these walls to become something else.” Under her plan the walls become large enough to be occupied, designed for multiple programs, like supermarkets, churches, and dwellings. “They can become spaces that help the informal communities by adding infrastructure. These communities are often ignored by the city services so my proposal asks, ‘How can these walls help the people living above them?’ So the walls cannot only provide amenities but also provide recognition to those communities.”

Mireya’s thesis consists of intricate, polychromatic models, with the research worked out through drawings. Though not officially presented as part of the thesis, Mireya has written stories for each of the spaces she has created. “I’ve always loved reading, especially magical realism,” she says, “All my projects have some sort of narrative component to them. It’s really linked to how I think.” As though there was not enough to do, even though it is not her native language, Mireya will be minoring in English literature through the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Her goal from five years earlier has been more than fulfilled. “I now have done things that I never thought I was going to be able to do. The school has given me so many opportunities. One of my models was exhibited at MoMA. Then I had another model in the Chicago Biennial. I have also been able to get really awesome internships. I now know how to handle materials and do drawings that I never thought I would be able to handle. I feel like five years ago I never thought any of that would be possible.”

After graduating Mireya plans on staying in New York for at least another year. During that time, she will be working at Peter Pennoyer Architects (Elizabeth Graziolo AR'95 is a partner there), with hopes of getting sponsorship to extend her U.S. visa. If not, she has a Spanish passport. Until the social, political, and economic turmoil in Venezuela settles down, she will be staying away from her native country. But she has long-term plans that should surprise no one who knows her. “My goal in life is to go back home and have a firm with my family and build there. Fabregas Studio or something like that.”

Parker Limon travelled even further than Mireya to attend The Cooper Union. He arrived from San Jose, California. He had set his sights on attending here while still a freshman in high school after a teacher steered his interest in mechanical drafting towards the discipline of architecture. He found Cooper on Wikipedia, saw the tiny acceptance rate, and kind of tabled his ambitions. “I was a pretty bad student with a poor work ethic,” he says. But after two years he transferred to a dual high school and college credit program at De Anza Community College where he turned his game around. “I took art history and every drawing course I could that seemed related to architecture.” He applied to The Cooper Union as his reach school. Upon receiving his acceptance letter, he threw out all the other applications.

Parker Limon travelled even further than Mireya to attend The Cooper Union. He arrived from San Jose, California. He had set his sights on attending here while still a freshman in high school after a teacher steered his interest in mechanical drafting towards the discipline of architecture. He found Cooper on Wikipedia, saw the tiny acceptance rate, and kind of tabled his ambitions. “I was a pretty bad student with a poor work ethic,” he says. But after two years he transferred to a dual high school and college credit program at De Anza Community College where he turned his game around. “I took art history and every drawing course I could that seemed related to architecture.” He applied to The Cooper Union as his reach school. Upon receiving his acceptance letter, he threw out all the other applications.

When asked about the impact of the change in tuition policy on his decision Parker says, “The tuition didn’t influence my decision so much because I was in a position where my parents could help me pay for college and they were thinking that I would go somewhere more expensive. But I was super lucky." Even so, it wasn't easy, “Being part of the first paying class resulted in this strange insecurity like you have to prove yourself as good as all the previous classes. So we grew up with that at Cooper. It has definitely influenced a lot of our practices in studio. We are always there. We work really, really hard. Almost too hard. I think we do good work, but it is rooted in this insecurity, I think. It’s a driver.”

He remembers well that first semester’s project, working on the Foundation Building model. “I think that architectonics studio is why our class is so close. It was our first studio course and we spent every waking hour on it. It was amazing.” He recalls moving the Foundation Building model around the actual Foundation Building during the following year, eventually packing it to go upstate, to Arts Letters & Numbers, a multi-purpose space founded by David Gersten. Parker is actually a little unsure of the model’s present location. “I can’t keep track of it. It’s weird. This rolling thing keeps rolling around.”

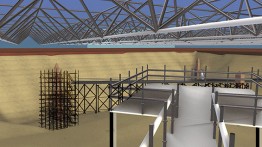

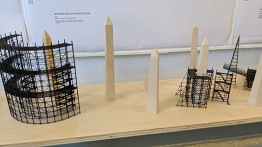

One wonders if the experience of moving an iconic building around played any role in Parker’s thesis proposal, “Moving Cleopatra's Needles from Artifact to Asset.” “I am proposing the repatriation of 21 ancient Egyptian obelisks,” he says. “It’s formulated to provoke thinking about how the meaning of monuments is made and how cultural value can be accumulated onto an object once considered part of a global patrimony.” Sited in Heliopolis, an ancient city of the sun, now part of Cairo, that had been essentially abandoned until recently, Parker’s proposal puts the obelisks, currently located in New York, London, Paris, Rome, Istanbul, and Egypt, in one place, along with an associated institution that he describes as the “inverse of the encyclopedic museum model.” He goes on, “The institution of Egyptology has its origins in the colonial project of Napoleon and has shaped the way we view that history today. That is something I am looking to contest.”

Parker’s thesis did not spring from an interest in Egyptology per se, but more of a desire to examine the network of things that act on an object. It started with an archival photograph of a barge shaped like a cigar. “It struck me as odd so I decided I wanted to draw it. I found out it was designed to move obelisks. Then I thought I could do a project on this. I started with researching the history of Cleopatra’s Needle, behind the Met. Last semester was an analysis of that obelisk’s movement from Egypt to New York.”

But the notion of siting his thesis in Egypt did not gel until a William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship funded a trip there. “At first I just planned an analysis of all the obelisks’ movement and proposing to orchestrate an event with cruise ships. But now it’s not that at all. The fellowship put me in the site and that was when I realized I needed to actually design something.”

As of this writing Parker is still considering his post-graduation work options. Though none of those positions are at a traditional architecture studio, all options will keep Parker in New York City. After a few years, he says he would like to go to graduate school and ultimately begin teaching. He describes his time at The Cooper Union as “formative,” building his confidence. “I think you have to develop an ego here pretty quickly. Some people came in with that. I definitely did not. And that is really important to learn. You have to be a person at the end of it.”

While Mireya and Parker traveled far to attend The Cooper Union, Zhenni Zhu has them both beat. She hails from Beijing, though she was born in Sichuan. Not only that, but for two years she studied civil engineering at UCLA before transferring here. “There was an alumnus of my high school whose civil engineering work I really admired. I thought the structural beauty inside his designs were really interesting and I wanted to pursue that. But after two years I got bored with doing all the calculations. I wanted something more creative,” Zhenni says. A friend told her about The Cooper Union’s school of architecture. “I did not have an art background,” she says. “I didn’t think I would get in, so I just did whatever I wanted on the home test. Later, when I received the acceptance letter on April Fool’s Day, I totally thought it was a joke.”

While Mireya and Parker traveled far to attend The Cooper Union, Zhenni Zhu has them both beat. She hails from Beijing, though she was born in Sichuan. Not only that, but for two years she studied civil engineering at UCLA before transferring here. “There was an alumnus of my high school whose civil engineering work I really admired. I thought the structural beauty inside his designs were really interesting and I wanted to pursue that. But after two years I got bored with doing all the calculations. I wanted something more creative,” Zhenni says. A friend told her about The Cooper Union’s school of architecture. “I did not have an art background,” she says. “I didn’t think I would get in, so I just did whatever I wanted on the home test. Later, when I received the acceptance letter on April Fool’s Day, I totally thought it was a joke.”

Seven years after she first started her undergraduate schooling Zhenni has finally culminated all that work into her thesis, “The Sunken Place – A Critique of Workamping Phenomena.” “My research subject is RV populations. I was interested in the topic of mobility. But then I discovered something really unexpected,” Zhenni says. Like most people she pictured the population of folks that drive recreational vehicles as belonging to a class of well-off pleasure seekers. But during her early research she discovered a curious sub-culture. “Some users of RVs are victims of the financial crisis of 2008. They lost their original homes and savings. So they were forced to live in RVs as an inexpensive option. Because of the financial burden they must constantly work seasonal jobs.”

Like other migrant laborers the “Workampers,” as they refer to themselves, follow the seasons, heading south for the winter and then spreading out during the warmer months. Recognizing this, one particular company identified a useful labor force. “Amazon has this program where they target these people,” Zhenni says. Called Amazon CamperForce, “the program started after the financial crisis as a way to attract seasonal labor. So these travelers go there during the winter holiday season, packing boxes and keeping up the stock in the warehouses. It’s hard work.”

Zhenni began to form a thesis topic. “A recreational vehicle used to represent an escape from urban life. But now it actually sets limits, or boundaries for people,” she says. Wishing to examine the lives and circumstances of this group, Zhenni applied for a William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship. And like most every other recipient, the travel it allowed completely changed her position, providing another facet to the story. “I went to interview many people during winter break, in Kentucky and Arizona. There are many Amazon CamperForce locations in Kentucky. Amazon doesn’t build campgrounds, but they contact campgrounds nearby and pay the fees when people stay there. To my surprise the workers don’t consider themselves as being exploited. They very much see themselves as enjoying leisure time and having less pressure dealing with a routine life. Workamping also becomes a way for them to keep their body and mind active when they are old.”

Zhenni’s thesis does not try to propose a “solution” to make the lives of this migrant labor force “better,” though it started out that way. “My initial thought was to improve the living condition for the workampers, such as providing infrastructure and programs that are necessary for supporting their nomadic lifestyle, either at campsites or at warehouses. However, this attempt seemed to redeem the working situation of the workampers. So, rather than resolving the problem, I attempt to use the architectural tools to critique the workamping phenomena, where the idea of the presumably ideal community is built on the presence of an invisible power. It reminds me of The Truman Show.”

So, using traditional drawings of plans and sections, as well as spare topographical models, Zhenni presents different ideas about what both Amazon and the workampers might see as the “perfect” space. One drawing includes a recreational area with a Ferris wheel. “The workampers follow a yearly movement cycle that has a series of fixed nodes. While they appear to escape from the urban world to pursue freedom, they cannot escape the controlled ‘utopia’ that has perverted the American Dream. “

Given the close relationship between Zhenni’s two undergraduate pursuits, one wonders if the former informed the latter. “It’s hard to say if civil engineering plays a role in my architectural work,” Zhenni says. “I feel like when I do architecture I don’t really get to that level of construction.” She did take two engineering courses during her time at Cooper, as well as classes in the School of Art. “We are required to take non-architecture courses. One of those I chose was material testing. We built actual beams and columns using the labs in the basement of 41 Cooper Square to test material strength. I wanted to see how those things actually work.”

After graduation Zhenni will take a year to explore and look for work. She is considering graduate school. “I like building. And that interest has carried through my seven years of school. My parents didn’t really want me to transfer. They thought I would get bored after seven years. It’s tough, but this is the road that I picked. It’s a long learning process. I think it will continue after I leave.”