From Clay and Cans to Sun-dappled Pavilion

POSTED ON: April 4, 2017

A team that includes Powell Draper, adjunct associate professor of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, and Max Dowd AR'16, has won the annual City of Dreams Pavilion Competition, which comes with an opportunity to construct a temporary installation on Governors Island during the Summer of 2017. Together with their colleagues Lisa Ramsburg, Josh Draper, and Ted Segal, Team Aesop, as they called themselves, proposed a work they dubbed "Cast & Place" that would use clay excavated in the city and walls cast from melted aluminum cans to create a structure that subtly references recycling through a social space. Their proposal responded to the competition's question, "What is the future of New York City?" taking top honors out of 100 submissions.

"We explored a number of ideas," Professor Draper says. "The specific avenue was sustainability. We chose to look at it particularly through materials. So, we started thinking about material flows and fell upon this concept of taking a waste stream and making it useful."

Professor Draper teaches Structures at the school and works as Director of Operations for the New York office of Schlaich Bergermann and Partner, an international structural engineering firm. He recruited Max Dowd for the pavilion project after seeing Max's 2016 thesis proposal that included his own mud brick-making machine as part of a master plan for low-cost housing in Kigali, Rwanda.

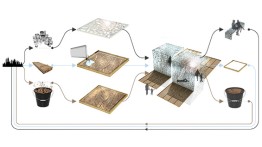

The team began its investigations with the history of the site. Governors Island is made up largely of fill from excavated subway tunnels. This inspired the idea of using clay dredged from the East River, something that takes place periodically, putting it into large frames and heating it to dry and crack. Aluminum, melted from recycled cans, would then be poured into the cracks, creating a lattice that, when removed from the mold, would be rigid enough to be used as building material.

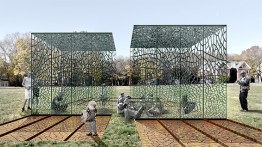

"Part of the structural poetics was that the cracks were lines of weakness in the clay that really speak to where the energy goes into that material," Max Dowd says. "By creating the positive, through the casting process, we create the reverse, a really strong lattice. We wanted a beautiful pavilion that has this dappled shadow and light. The clay molds would then be laid down so that visitors could read the process and experience the lifecycle of that material. During the summer there would be rain showers when the clay would become soaked and create reflecting pools around the pavilion. Then, cyclically, it would dry and crack."

The proposal would use 300,000 cans, which sounds like a lot but is, in fact, the number cans used by New York City in one hour. Many of the cans will be supplied by Sure We Can, a Brooklyn-based non-profit community space for local "canners" that wander the streets collecting cans and bottles. Part of the proposal's concept includes elements of local social engagement. If built, the pavilion would include programming for such organizations to present information to the public.

"We still have some technical challenges to overcome but overall we have samples and prototypes and we are confident we can make it work," Professor Draper says. "Going in, if you had asked me if the technical or logistical challenges would be the greater hurdle, I would have said technical. But the logistical has been the big challenge. It's an incredible number of cans, 300,000, to build these panels. That's because there's not a lot of aluminum in cans. So obtaining them, then transporting them to the Grounds for Sculpture, in New Jersey, that we are using to cast the panels, is a challenge. We started this proposal looking at material supply streams from the outside and what we have found is we are inserted into it now. We've been ambitious."

While the City of Dreams award offers prestige, being one of the few small-scale experimental architectural competitions in New York, it requires the winners to obtain outside funding to support the actual building of the pavilion. To fundraise for that the Aesop team organized a Kickstarter campaign that successfully finished at the end of March. "We had a flurry of support at the end, including from members of the Cooper Union community, which we were grateful for," Professor Draper says. "We are super excited and optimistic that it is actually going to happen."

"It was fascinating for me as a young architect to work with such talented engineers," Max Dowd says. "The project is a real testament to that collaboration. We couldn't have done it without a serious engineering team who were architecturally-minded. From my personal experience at Cooper, the most exciting things to happen are when I collaborate with people who are outside the architectural bubble. You have different expertise, interests and ideas. That's where I think the real magic territory is."