A Building You Should Know: The John S. Chase Residence

Fri, Mar 12, 2021 12pm - Fri, Apr 23, 2021 12pm

In 1954, John Chase petitioned the state of Texas for special permission to take the architecture licensing exam. No architect in Houston, where Chase and his wife, Drucie, had moved after his graduation from the University of Texas in 1952, would hire him for professional internship. Remarkably, the state agreed to his request. In 1954, John Saunders Chase became the first Black licensed architect in Texas. Even before licensure, Chase—affable and gregarious, and, with Drucie, deeply involved in his community—was receiving commissions, from churches to professional offices to houses. The mid-1950s and 1960s were a period of growth for the Black middle and professional classes in Houston. Chase’s office was now official and thriving (a gallery of Chase's work is available here).

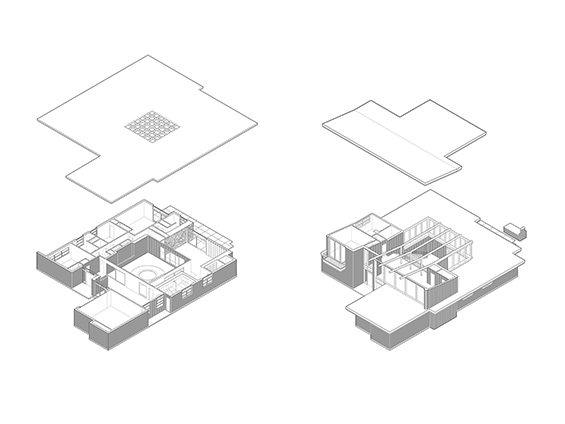

Stage One, 1959

The house Chase completed in Houston for his family in 1959—and then substantially altered in 1968—was thus a remarkable personal accomplishment. It was also a crucial meeting place in Houston’s social and political life (and beyond), and a landmark in American architecture: the Chase Residence was one of the first Modernist houses to use an enclosed interior courtyard as a true extension of the public realm of the house, not as a garden, lightwell, or circulation space.

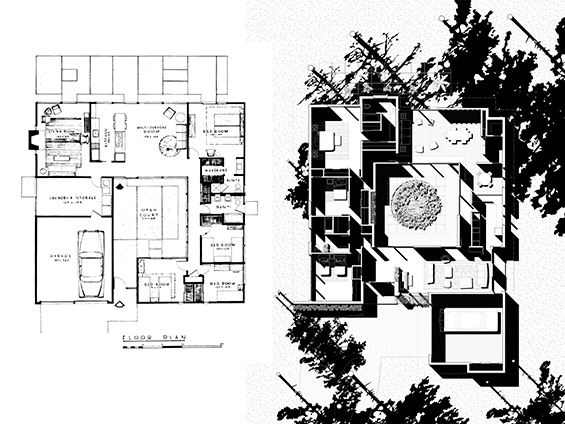

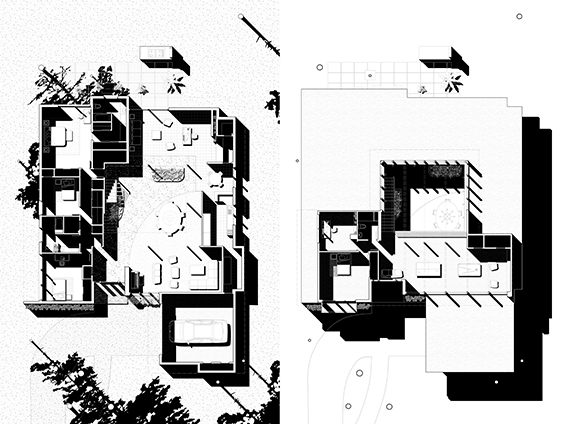

Though clearly related to experimental houses that the architects Anshen and Allen were designing for the California developer Joseph Eichler—evident in the below comparison—the Chase Residence is distinct in important ways.

At first glance these plans almost seem mirror images. But you enter the E-11 courtyard first, then proceed to the “front” door, passing a variety of service and private rooms. This allows the public rooms to face the backyard—for Eichler, the crucial post-War family space. The Chase plan generates an entirely different experience. You come to the opaque front doors first, and then enter the house before you discover the courtyard. As in ancient prototypes, this courtyard is the important place you come to, the mysterious center of the house, its own world removed, a window to the re-discovered sky—and also the extension of all the public rooms surrounding it.

Chase was on to a great idea, and while other progressive architects (like Eliot Noyes, Marcel Breuer, and Philip Johnson) experimented with similar ideas, there were no contemporary Modernist examples using the court in exactly this manner. Coincidentally, by the mid-1960s Eichler had started producing houses—including his own home—with courtyards similar to that at the Chase Residence.

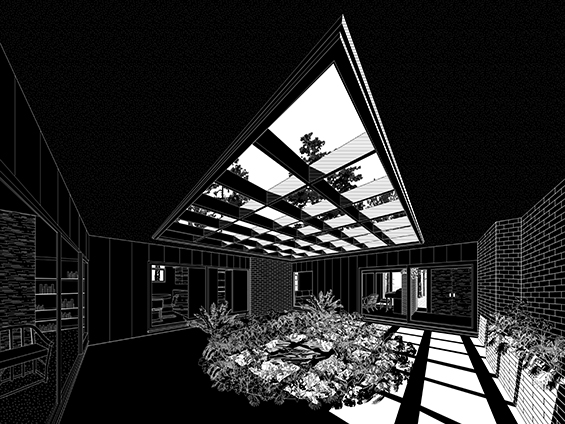

Drucie didn’t initially think the big outside room would serve for social functions, which she and Chase, deeply involved in the life of the city, were hosting with increasing frequency. But Drucie found visitors gravitated to the courtyard, and began to plan accordingly. She once spent a week preparing for a big party to be held in the court, only to have it snow—the rarest occurrence in Houston—the night of the event. Drucie feared ruin; instead, people stood transfixed in front of the rolling doors, the snow falling magically into the center of the house.

The term paradise is derived from the Persian word for a walled garden, and Chase family members describe the courtyard as paradisiacal. Late in his life, Chase proposed building the house again, exactly as it had originally been, elsewhere in Houston—an aim cut short by his death in 2012 (Drucie passed away earlier this year).

According to Drucie, the courtyard’s original purpose was as a safe play space. But its active social use and Chase’s desire to remake the courtyard suggest a more complex purpose than practicality. I have a theory based solely on the evidence of the hidden richness of this architecture: John and Drucie’s life required a never-ending negotiation through a public realm in which arbitrary power was decidedly not in their control, and often aligned against them. In that context, a courtyard house made sense. Ian McHarg echoed this in his 1955 Architectural Record article on the promise of urban courtyard houses, noting “In the court house the individual has freedom for personal expression which cannot obtrude on the public.”

Stage Two, 1968

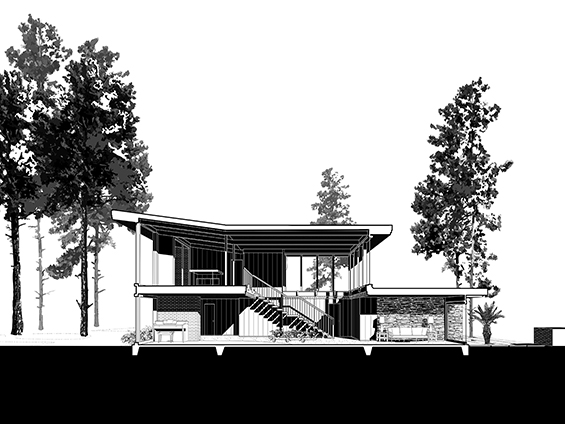

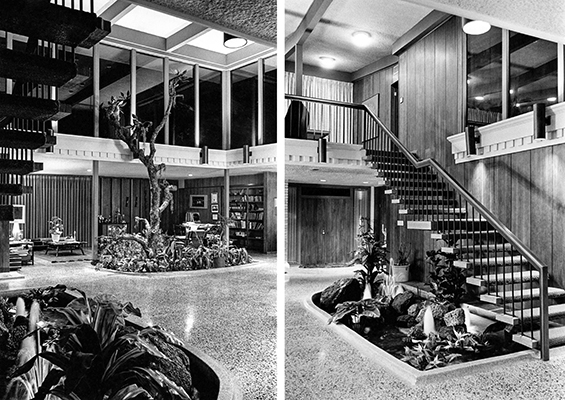

By the late 1960s the Chase family had three growing children, and John and Drucie were hosting many social, community, and political events. In 1968, Chase enclosed the courtyard as a grand two-story room and added an upper floor with a game room, bedroom, bathroom, and office. Chase changed the house’s character as well, evident in the repetitive trim blocks he added to the original, minimal fascia boards along the roof edges. This geometric decoration, also used indoors, subtly shifted the building’s style from the elegant elitism of Mies to the confident populism of Wright.

A photograph taken at a party of Saundria Chase (John and Drucie’s third child) with Mickey Leland is emblematic of the renovated house. Leland was one of five minority candidates elected as state representatives after Texas switched to single-member districts in 1972, and was a prominent U.S. Congressman from 1978 until his tragic death in an airplane crash in 1989. Chase and Leland are surrounded by white and Black Houstonians, all smiling, bathed in daylight from the great, projecting light monitor that Chase superimposed over the courtyard. Its vertically proportioned glass directly fastened to the roof supports recalls Wright’s Usonian houses, which, like Eichler homes, sought to make Modern architecture broadly available.

The light monitor is also in dialog with a fine new stair, the open risers of which partly shield arriving guests, granting them a full view of the great room and adjacent, open, social spaces. The landing halfway up served as a platform from which Chase and Drucie and prominent visitors—including Thurgood Marshall, Muhammad Ali, Gregory Peck, Vernon Jordan, Lloyd Bentsen, and John Connolly (then Governor of Texas)—often addressed their assembled guests.

It is tempting to understand the architectural transformation Chase undertook as the making of a generous and efficient social stage. But perhaps it is more than that. Frank Lloyd Wright argued that in architecture there is no distinction between the social construction of a house and the political construction of society. Describing the Usonian House for a 1953 exhibition at the Guggenheim, Wright is close to describing the Chase Residence:

“Here the original comes back to say hello to you afresh and to see if you recognize it for what it was and still is—a home for our people in the spirit in which democracy was conceived: the individual integrate and free in an environment of his own, appropriate to his circumstances—a life as beautiful as he can make it—with her of course.”

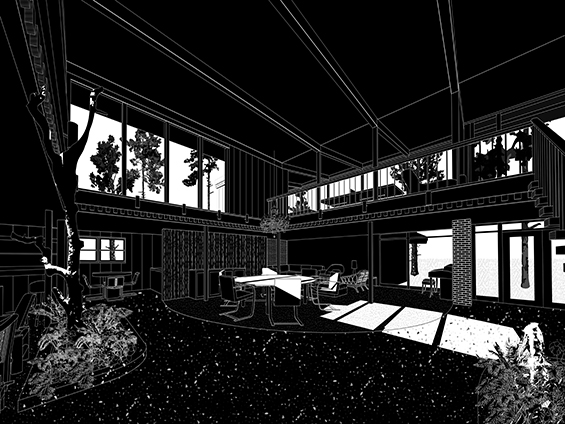

Exchanging the courtyard for the great room marked a shift in Chase’s architecture to a new public certainty. You can see that perhaps most clearly in the full-height band of north-facing windows Chase set over the opaque front wall of the original house. They seem far too tall for the first floor, and are in fact oversized. Their height is the result of Chase tilting the northern half of the new upper roof up. The intended effect on the interior is straightforward: the tilted ceiling links the new mezzanine to the public space below. The effect on the exterior of the house is profound.

You can see it best at night, when the house becomes a lantern in the city.

Chase Residence Drawings

The black and white drawings presented here were prepared for Chasing Perfection: The Legacy of John S. Chase presented at the University of Texas School of Architecture (UTSOA), and for the book John S. Chase – The Chase Residence that I wrote with Stephen Fox (Tower Books, 2020). The book’s drawings (available here) were made under my supervision by a group of UTSOA graduate students: Brooke Burnside, Sarah Spielman, and Wei Zhou. Many others helped in making our book, including members of the Chase family, curators at the Houston Public Library, the Houston architect Ben Koush, and the photographers whose work is included here and in the gallery on Chase’s work (see image credits below).

Few of Chase’s drawings remain. We derived the stage one drawings from a preliminary permit set, photographs, and—working backwards—from field measurements of the existing house, substantial portions of which remain the same as when first built. No drawings remain of the 1968 revision. They were likely thrown out (as were most of Chase’s office drawings), but there were few drawings to begin with. Chase would meet every morning with the builder and draw out on the floor what he wanted, often at full scale. Our drawings of the second stage estimate, as closely as possible, the 1968 revision by working from photographs made in the intervening years.

According to family members, the house and landscaping were in a state of continuous flux, making it impossible to fix them decisively as a set of facts, furnishings, or possessions. In making these drawings, we took this into account, focusing instead on the spatial qualities of the architecture in light. The style of the drawings references graphic tropes used in the early 1960s and our thoughts about how they might be translated to digital formats.

— David Heymann, AR’84

Harwell Hamilton Harris Regents Professor, University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture

On March 25, from 6:30pm to 8:30pm, David Heymann will present an exhibition lecture via Zoom. Registration and event details are available here.

Image Credits

Header, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 12: Drawings by David Heymann, Brooke Burnside, Sarah Spielman, and Wei Zhou.

1, 11: Courtesy of MSS 0113 John and Drucie Chase Collection. African American Library at the Gregory School, Houston Public Library.

3: Courtesy of Anshen and Allen Architects.

6, 10: Courtesy of the Chase family, photographer unknown.

9, 13: Courtesy of Hester + Hardway, photographer.