"Bernhard Hoesli: Collages" Reveals the Story Behind the Artworks

POSTED ON: March 25, 2014

Bernhard Hoesli: Collages, an exhibition of rarely exhibited artworks by the 20th century Swiss artist, architect and educator opens today at the Arthur A. Houghton Jr. Gallery until April 19th. The 52 works that comprise the show, all of them created privately using materials typically found at home, provide an otherwise overlooked glimpse into a major shift in modern art making and architectural process. That they are also touchingly intimate and stunningly crafted makes the experience of viewing them all the more enjoyable.

"These collages have a place in art history when you think about modern art or collage or mixed media art as we know it today," says Christina Betanzos Pint, an architect who first organized the show in 2001 for the University of Tennessee, where she taught at the time. "They have their spot in the genealogy of what started with Juan Gris and Picasso and those who started collage way back in the early Cubist era. These collages are a direct result of all of those developments."

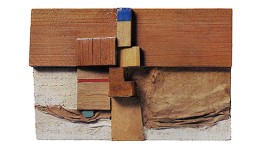

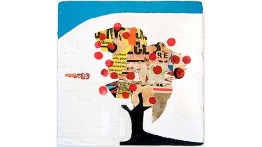

Created between 1963 and his death in 1984, Hoesli's collages, which are all on a small scale, have been arranged around the gallery in groups that relate to each other in terms of their color, texture or composition. For example, earlier works depict a more traditional "architectural" sensibility because of their resemblance to a figure-ground condition. Later works share broader investigations of color and texture. The variety of materials used and the breadth of ideas being explored in these meticulously constructed, masterfully designed works reveals an artistic mind unlimited in its interests.

Created between 1963 and his death in 1984, Hoesli's collages, which are all on a small scale, have been arranged around the gallery in groups that relate to each other in terms of their color, texture or composition. For example, earlier works depict a more traditional "architectural" sensibility because of their resemblance to a figure-ground condition. Later works share broader investigations of color and texture. The variety of materials used and the breadth of ideas being explored in these meticulously constructed, masterfully designed works reveals an artistic mind unlimited in its interests.

Many works feature cartoonish faces or figurative shapes that Hoesli drew onto the surface. Others focus on typographical and color juxtapositions, as on a plastic shopping bag he found to be an inspiring surface. Besides using carefully shaped paper cutouts, Hoesli also used materials such as corrugated cardboard, flattened metal cans and even sand. The objects he used to overlay the collages are equally varied and even include household items such as a leather school satchel, a doorstop and a pair of shoes.

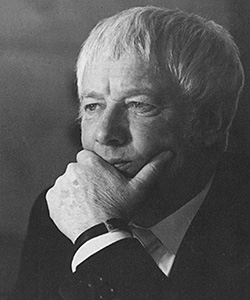

The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture has brought the collages to The Cooper Union, on a short tour that started at the University of Texas at Arlington, in large part because of Bernhard Hoesli's association with John Hejduk, the first dean of the school of architecture. They were both members of the group of architectural educators who came to be known as The Texas Rangers, having taught together at the University of Texas at Austin in the early to mid 1950s. "That time was crucial in terms of the evolution of architectural education," Steven Hillyer, director of the archive of the school of architecture, says. "Hejduk and Hoesli were there with Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky, among others, for a short period of time, as they were consciously forming a new approach to teaching and defining architecture."

The new approach focused on the analysis and critique of contemporary architecture and the interrelationship of architectural elements in organizing volume and space. "I think collage was the umbrella that explained everything Hoesli did: urban design, architecture or art," Christina Betanzos Pint says. "I would be surprised if he has a piece of architecture that didn't have an explanation in collage." Hoesli took the new approach back to Switzerland, where he began rebuilding the first-year architectural curriculum at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH). His contributions to teaching architecture, to say nothing of his collage work, are perhaps less well known in the United States than they should be. "I feel that he is underrecognized by today’s students, given his influence," Hillyer says.

Yet the works on display in the Aurthur A. Houghton Gallery were never part of a pedagogical exercise or necessarily meant for public display. They were constructed at home with whatever was at hand, largely for the pleasure of Hoesli and his family. The shoes, for example, belonged to Hoesli's daughter, Regina. They are a pair of black flats, well worn, with tiny scraps of vibrantly colored paper layered over the front half. They exemplify the intimacy of all the works. Every piece has a verso that includes dates, dedications, notes about the time and place of creation and even bits of prosody. One reads, "Memories of things long past." Another reveals a reconsideration about which direction should be up. Some works are displayed perpendicularly to the wall so viewers can see the diary-like entries. Hoesli would return to many of the works over the course of years, noting the revisit each time on the verso side.

"I really appreciate the idea that you don't make a work that’s necessarily fixed. You go back and revisit." Steven Hillyer says. "And not just over the period of a day or week; it could be years later. That’s a method of process that should be studied, one of the many reasons I believe these collages are important for our students to see.”

The works of Berhnard Hoesli: Collages have a place in art and architectural history, providing a glimpse into the process and life of a key fomenter of the art and architecture of the modern age. But even those who have little interest in such history can treat themselves to a purely aesthetic experience. "The collages are just beautiful. That's the other reason to see them," Christina Betanzos Pint, says. "From the tiny ones to the larger ones, they are exquisite pieces of manipulation where you can imagine him taking tweezers and placing dots of color. The amount of detail and care actually taken in putting these collages together deserves to be seen."