Seeing the World through the Eyes of Ashley Bryan, Storyteller

POSTED ON: June 1, 2009

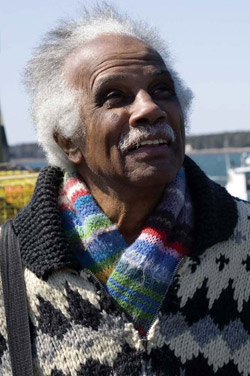

Ashley Bryan (A’46), a dignified white-haired man with a matching white moustache, stands holding a book in his hand, in front of a group of children. He starts speaking, a gravelly voice emanating from his thin frame. “This is a story about a little boy with a very long name,”he says quietly.This is when everything changes. Bryan moves forward, punctuating the next line physically, moving his arms almost as if he were conducting an orchestra. “Once,”he says, the word spinning out, starting out quiet, and taking flight with the rest of the sentence, “the little boy, he had a very long name.”Each word has a unique sound, sometimes echoing and emphasizing the word’s meaning, as when he stretches out “long.” Bryan barely looks at the book, Turtle Knows Your Name, though he holds it open as he speaks. “His name was,” he continues, and then sing songs the next syllables: “Up-silima-na.”His free hand marks the rhythm, his bent knees click in time with it. “Can you say that?” he asks, a sudden serious tone emerging in his voice; The kids gleefully respond, copying his phrasing, “Up-sili-ma-na!” The story unfolds with a collection of sounds, sometimes percussive, sometimes gentle, that can’t be read from the page—Bryan snaps his fingers and modulates his voice from high to low, soft to loud, while he encourages his audience to clap, putting his hand to his ear when he wants them to repeat after him. His story fills the space with sound and movement; Bryan doesn’t just read a story, he creates a world through his performance of it. Bryan, an acclaimed illustrator and author best known for his retelling of African tales, has just won the prestigious 2009 Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for his lifetime contribution to children’s literature.He explains that, “we don’t have a performance aspect to our poetry in Western culture.” It is just this element that his work has sought to introduce. In a way, it’s hardly surprising that he has chosen this route, which heavily emphasizes the importance of community (a performance, of course, necessitates an audience): throughout his long life—he was born in 1923—Bryan has been sustained by the various communities of which he is a part. “I have such a reverence for others, for what they have to offer,” he says, “I always feel that I am in the other’s debt.”He quotes a line from Senegalese poet Léopold Sédar Senghor: Je ne sais en quel temps c’était, je confonds toujours l’enfance et l’Eden—Comme je mêle laMort et la Vie—un pont de douceur les relie…He translates this as “I didn’t know when it was, I always confuse the past and future, the way I mix up death and life—they are connected only by a tender bridge.” Bryan says that for him, storytelling is this tender bridge, not only connecting past and future, but connecting people. “This is why stories are at the heart of civilization.”

Bryan, an acclaimed illustrator and author best known for his retelling of African tales, has just won the prestigious 2009 Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for his lifetime contribution to children’s literature.He explains that, “we don’t have a performance aspect to our poetry in Western culture.” It is just this element that his work has sought to introduce. In a way, it’s hardly surprising that he has chosen this route, which heavily emphasizes the importance of community (a performance, of course, necessitates an audience): throughout his long life—he was born in 1923—Bryan has been sustained by the various communities of which he is a part. “I have such a reverence for others, for what they have to offer,” he says, “I always feel that I am in the other’s debt.”He quotes a line from Senegalese poet Léopold Sédar Senghor: Je ne sais en quel temps c’était, je confonds toujours l’enfance et l’Eden—Comme je mêle laMort et la Vie—un pont de douceur les relie…He translates this as “I didn’t know when it was, I always confuse the past and future, the way I mix up death and life—they are connected only by a tender bridge.” Bryan says that for him, storytelling is this tender bridge, not only connecting past and future, but connecting people. “This is why stories are at the heart of civilization.”

As a child, he was nurtured by his parents’ inclusive style, where the lines between‘family’ and‘community’ were blurred. He lived with five sisters and brothers, as well as three orphaned cousins, whom his parents had adopted; and Bryan’s mother would consider any good friend of his as one of her own children. This inclusivity was echoed in his Bronx neighborhood and its many ethnic groups: as he puts it, “there were Germans, Italians, Irish, French and a great Jewish community in my neighborhood.”Growing up in this atmosphere, Bryan accepted diversity as the norm.Nothing strange then,when he and two of his siblings let his parents know that they wanted to attend the beautiful church next to his elementary school. “We told our parents that we wanted to go to the church where the bells ring on Sunday morning,with the beautiful stained glass windows, so that was where we went.”He laughs wholeheartedly at the memory. “It turned out to be a German Lutheran church, and it had services in German and English.We didn’t know it at the time, but it turned out that we were the first black family to enter that church. But the superintendent took us into the primary department.” Bryan sees it as natural that he became an artist, partially thanks to his parents, but also because of the era in which he grew up.His parents, who had moved to New York City from Antigua, both had a love of beauty and education. But there was an equal insistence upon self-sufficiency, because there were so many kids in the household. “My parents simply said,” he pauses for a moment, and then, his voice deepening, booms, “‘learn to entertain yourselves!’”As luck would have it, the upside of growing\ up during the Depression was that Roosevelt’s Works Program Administration (WPA) program was in full swing, so many of Bryan’s teachers were artists and musicians. Entertaining himself meant drawing and painting; it also meant going over to the elderly people in his neighborhood, as they sat on their park benches, and asking to hear stories. “They’d seen so much,”he explains, “at the turn of the century and after the First World War, and I was fascinated.” In kindergarten, Bryan’s teacher underlined the importance of creativity when she had them make illustrated books of the alphabet. “You’ve now published your first limited edition,” she told the kids. Bryan sees this as a seminal moment; from here on in, he would continually make illustrated books, in addition to his paintings and drawings.

Bryan sees it as natural that he became an artist, partially thanks to his parents, but also because of the era in which he grew up.His parents, who had moved to New York City from Antigua, both had a love of beauty and education. But there was an equal insistence upon self-sufficiency, because there were so many kids in the household. “My parents simply said,” he pauses for a moment, and then, his voice deepening, booms, “‘learn to entertain yourselves!’”As luck would have it, the upside of growing\ up during the Depression was that Roosevelt’s Works Program Administration (WPA) program was in full swing, so many of Bryan’s teachers were artists and musicians. Entertaining himself meant drawing and painting; it also meant going over to the elderly people in his neighborhood, as they sat on their park benches, and asking to hear stories. “They’d seen so much,”he explains, “at the turn of the century and after the First World War, and I was fascinated.” In kindergarten, Bryan’s teacher underlined the importance of creativity when she had them make illustrated books of the alphabet. “You’ve now published your first limited edition,” she told the kids. Bryan sees this as a seminal moment; from here on in, he would continually make illustrated books, in addition to his paintings and drawings.

Bryan had continued to flourish during his time at Theodore Roosevelt High School, and decided to apply to art college. It was here that racism had its first major impact on him. He applied to one of the best-known art school’s at the time, but they would not give him a scholarship; he was told that “‘this is the best portfolio we have seen, but it would be a waste to give a scholarship to a colored person.’”Bryan doesn’t mention the word ‘racism,’ but in an understated way, says, “So that was my introduction to that.” This isn’t to say that he didn’t think of himself as black; yet, he had managed largely to avoid the scourge of racism because of the strong groundwork put in place by his parents and his extended community. “I had grown up knowing I was black, and that I was part of the black community. But, all of my teachers were white, from elementary to high school, and all of them encouraged me and helped me build that strong portfolio.”That robust community was there for him and cultivated a resiliency in him, an ability to look at difficult situations and instead of running away, to question them. “When I went back to Theodore Roosevelt and told my teachers what had happened, they said, ‘look, Ashley, come back and take a postgraduate course with us, and develop your portfolio, work on the senior yearbook, take whatever classes you’d like, and in the summer, take the exam for The Cooper Union. They do not see you there.’” He worked hard, and took the exam that summer. “I was fortunate,”Bryan says simply. “You just put your work on the tray with your name and address, and left The Great Hall.”However, he also notes that he was the only black person in his class.

A view of Ashley Bryan’s studio.

Bryan began attending The Cooper Union in 1940. And, at Cooper, Bryan found a similar sense of community to that of his childhood. At 86, he has seen the passing away of many of his classmates. But, it’s clear that he’s delighted in the friendships he made there. “I made friends for life at Cooper—we’ve followed each other and supported each other’s work. Of course, of my generation, there are few who are still alive and I’m still close to them: Al and Lotte Blaustein, John Ross and his wife Clare Romano. I hold to them.” Before he could complete his studies at Cooper, Bryan was drafted into the US Army. World War II was being waged in Europe, and he was sent to fight in France in 1942. When he returned to New York in 1946, he was left terribly unsettled by the experience: “I came back and finished the degree at Cooper, but like most veterans, I was so spun around. I found that I couldn’t go straight on with painting.” Like his earlier experience with racism, though, he couldn’t just accept the horrors of war. He felt he needed to understand what had happened in Germany during the war. “I wanted to understand why we select war, even though we know the tragedies and destruction that come with it. So I thought philosophy would give me some answers.” He attended Columbia University, where he earned a degree in philosophy, but found that it couldn’t give him all the answers he needed, so he returned to Europe, at first spending a year in Aix-en-Provence, in southern France, under the GI Bill. From there he moved on to Freiburg, Germany, with a Fulbright. “Remember,” he says, “my closest friends whom I’d grown up with and who I was still really close to were German, from the German Lutheran Church. I asked myself why they were different from the people in Germany. And what I came to understand is that when people are under dictatorial force, when they know that their jobs, their families and their lives are in danger if they go by their conscience, they often feed into what the demand is.” “We are all human,”Bryan sums up quietly. “I’ve seen this as a pattern throughout the world, one group against the other, one religion against another, one ethnicity against another; so it’s universal. But there’s also equally a universal desire to express a relationship to what is human in each of us. The desire is so strong.”He pauses momentarily. “The arts are our weapon,”he continues, “because just as we are all human, so we are all responsive aesthetically to being human. It’s what the arts open up; this investing of one’s life into trying to understand what it is to be. This is the philosophy that wends through Bryan’s life and work, linking them inextricably together. Back in the United States, Bryan was teaching at various times at Queen’s College CUNY and Lafayette College in Pennsylvania, and finally at Dartmouth College (where he remained until 1986). He also had a studio on Tremont Avenue in the Bronx. His interest in stories and cultures led him to reading African folk tales, and preparing illustrations for them, in addition to his painting and teaching work. In the early 1960s, Jean Karl,who was an editor at Atheneum (a Simon & Schuster imprint) heard about Bryan and came to his studio. He thought she was there to see his paintings, but she was also intrigued by the African folktale prints he had been making. She didn’t say much, but the next day, a contract arrived. “And that,” he says, understated once again, “is how I moved from my early limited editions to publishing on a wider scale.”

“We are all human,”Bryan sums up quietly. “I’ve seen this as a pattern throughout the world, one group against the other, one religion against another, one ethnicity against another; so it’s universal. But there’s also equally a universal desire to express a relationship to what is human in each of us. The desire is so strong.”He pauses momentarily. “The arts are our weapon,”he continues, “because just as we are all human, so we are all responsive aesthetically to being human. It’s what the arts open up; this investing of one’s life into trying to understand what it is to be. This is the philosophy that wends through Bryan’s life and work, linking them inextricably together. Back in the United States, Bryan was teaching at various times at Queen’s College CUNY and Lafayette College in Pennsylvania, and finally at Dartmouth College (where he remained until 1986). He also had a studio on Tremont Avenue in the Bronx. His interest in stories and cultures led him to reading African folk tales, and preparing illustrations for them, in addition to his painting and teaching work. In the early 1960s, Jean Karl,who was an editor at Atheneum (a Simon & Schuster imprint) heard about Bryan and came to his studio. He thought she was there to see his paintings, but she was also intrigued by the African folktale prints he had been making. She didn’t say much, but the next day, a contract arrived. “And that,” he says, understated once again, “is how I moved from my early limited editions to publishing on a wider scale.”

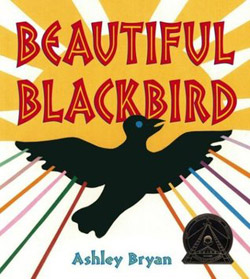

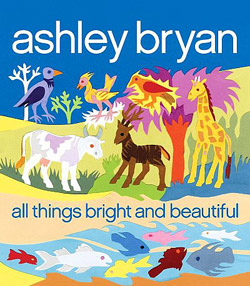

And so, in 1965, when an article by Nancy Larrick came out in the Saturday Review of Books entitled “The All White World of Children’s Books,” Bryan was ideally positioned to use his art as away to overcome this inequity. It took awhile to develop the work, as he wasn’t pleased with the stilted way in which the folktales had been translated—often just word for word in an attempt by linguists and anthropologists to record the hundreds of languages that they encountered. Karl encouraged him to rewrite them in his own style. He realized that the oral tradition, which is so lacking in the poetry of Western culture, was what he was after. “I went to the black American poets, because that was the voice I was after for these stories,” he explains. He also drew on the other oral traditions he had encountered in his travels, from French and Indian folktales, to black American spirituals, as well as his own experiences as a child in the 1930s, listening to the stories of his family and neighbors in the Bronx. He used the cadences of the spoken word to bring the stories alive, bouncing off the bright colors of his illustrations. Not only did Bryan’s oral storytelling act as a ‘tender bridge’ between his young listeners and an African history of which they were all too often unaware, but it also linked reading with enjoyment, and equally importantly, with a sense of belonging. Book and performance are of equal importance,he says: “I always hold the book, so that no matter what my voice does, the children can see the link to the book.” He published the first of the African folktales, The Ox of the Wonderful Horns and Other African Folktales, in 1971, and many more followed, including several illustrated books of black American spirituals, as well as the ever-popular Beautiful Blackbird in 2004. Bryan’s sense of community continues to inform his life, and he has added community after community to his family. He has been living on Little Cranberry Isle off the coast of Maine for decades; he has an open door policy and happily welcomes visitors whether he knows them personally or not. He had originally started spending summers there in 1946 when he was awarded a place at the newly opened Skowhegan School of Art in Maine. But, never one to stay in one place for very long, he also spends time in Antigua and is constantly traveling. For example, he recently returned from a trip to Kenya, where he has been going for the past ten years. There, he worked with Kemi Nix, of Atlanta’s Westminster School, who runs a reading program for disadvantaged children. Bryan was so impressed by the lengths the children would go to for their education in one poor rural town north of Nairobi, walking anywhere from one to six miles each way to attend school, that he decided to raise funds to open a library, in collaboration with Charity Mwangi, one of the women who had invited Nix to her school, Mount Kenya Academy Primary, to run the reading program.

He published the first of the African folktales, The Ox of the Wonderful Horns and Other African Folktales, in 1971, and many more followed, including several illustrated books of black American spirituals, as well as the ever-popular Beautiful Blackbird in 2004. Bryan’s sense of community continues to inform his life, and he has added community after community to his family. He has been living on Little Cranberry Isle off the coast of Maine for decades; he has an open door policy and happily welcomes visitors whether he knows them personally or not. He had originally started spending summers there in 1946 when he was awarded a place at the newly opened Skowhegan School of Art in Maine. But, never one to stay in one place for very long, he also spends time in Antigua and is constantly traveling. For example, he recently returned from a trip to Kenya, where he has been going for the past ten years. There, he worked with Kemi Nix, of Atlanta’s Westminster School, who runs a reading program for disadvantaged children. Bryan was so impressed by the lengths the children would go to for their education in one poor rural town north of Nairobi, walking anywhere from one to six miles each way to attend school, that he decided to raise funds to open a library, in collaboration with Charity Mwangi, one of the women who had invited Nix to her school, Mount Kenya Academy Primary, to run the reading program.

Despite the many obstacles he has overcome and the hardship that he has known, Bryan is remarkably upbeat, though always realistic. “We only have now,” he says. “So we have to make the most of the present.” It’s only in this moment—this moment, which is the tender bridge—Bryan feels, that we have the opportunity to seek meaningful interactions with each other. “Man has reached a point where there is huge potential for devastation and destruction,” he says. “So we must then try to tap what is meaningful in us, to find some spirit of what it is to be peaceful as human beings and to live and to create within that.” By telling his stories in a way that not only emphasizes the idea of community, but indeed relies upon it, Bryan has ensured that these tender bridges we build are a great deal stronger.

Ashley Bryan’s autobiography, Words to My Life’s Song, was published in January of 2009 by Atheneum.He has been awarded the Coretta Scott King Award numerous times for his children’s literature, and in 2008, he was honored as a Library Lion by the New York Public Library, along with playwright Edward Albee, screenwriter and essayist Nora Ephorn and novelist Salman Rushdie. He has received two lifetime achievement awards, most recently the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award in 2009 for his substantial contribution to children’s literature, as well as the Arbuthnot Prize in 1990.