Morgan Lewis

This slideshow is part of: 2013–2014 Fellowship Recipients

Tracing Follies

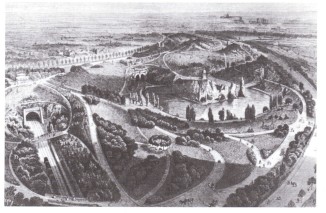

“To put together into one garden all times and all places” was the desire of the 18th Century Landscape Architect Louis Carmontelle when he set out on his most ambitious project, the Parc Monceau. Its chaotic and disjointed plan shows an assemblage of diverse fragmented follies connected by the loosest and most meandering of paths. When I first came across the plan in a book of European gardens it seemed impossible to understand its spatial hierarchy, or the purpose of this strange collection of disparate elements. There was something compelling about a composition that appeared so evasive, and so different from the garden-as-room plans I had been looking at up to that point in my thesis.

Although I went to Paris to explore the entire works of Carmontelle, it was walking in the garden at Monceau that was foremost in my mind. The garden, comprised a network of follies in a miniature landscape, is now enclosed by the majestic urban plan of Paris. The follies were of unclassifiable age and placed in unintelligible order. Roman temples were to be found next to Gothic arches and Egyptian tombs. Its creator, Carmontelle, stated that he designed this collection of pastiche fragments as “a tour of the world and its history.” This was not an effort to achieve an encyclopedic comprehension but its reverse; to achieve an environment that was “simply a fantasy.” The ultimate purpose of this disorienting fantasy was to become the stage set for the most licentious and pleasurable of acts of court. Here, in the decade before the Revolution, the French aristocracy played and courted in a setting that shockingly transgressed conventional boundaries of time, taste and the borders between the natural and the architectural. Its irrational, spasmodic plan sought to avoid any focus or aim beyond its own satisfying gratification.

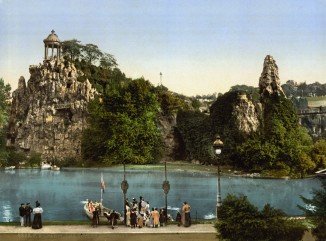

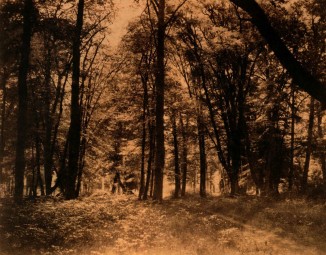

I visited a number of other historic gardens, landscapes and archives during my nine days in Paris, from the 17th century Jardin de Luxembourg to the forests of Fontainebleau – brought to fame by the Impressionists – to the Parc de la Villette of the 1980s. The experience had a wide impact on the development of my thesis, which includes the development of a temporary garden in South London as part of a hypothetical intervention into a speculative master plan. Prior to receiving the William Cooper Mack Fellowship I had been focused primarily on the particular garden that had been on my site. The trip opened me up to a French tradition that was new to me – the garden as a fantasy landscape that could be enjoyed through theatrical play. Furthermore it showed how a fragmented ruined architecture could speak of a past that has been irrevocably lost as well as how those fragments could play a critical role as an element in a new composition.

Parc Monceau, 1779

Buttes-Chaumont, 19th C. Engraving

Le Pyramide, Parc Monceau

A transparency and its machine

Buttes-Chaumont, c. 1920

Louis Carmontelle, Panorama Transparent d'un Paysage Imaginaire, 1790

Tree at Fontainebleu