Prof. Lowengard Delivers Keynote on the Early History of Color Printing

POSTED ON: October 10, 2013

Dr. Sarah Lowengard, Adjunct Associate Professor in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, will deliver the keynote address at the annual conference of the American Printing History Association this month. The talk will take place in New York at the historic Grolier Club, North America's first and oldest club dedicated to the art of the book and works on paper. Prof. Lowengard, who has taught the history of science and technology courses at The Cooper Union since 2006, was invited due to her specialization in the history of printing in color, the subject of the APHA conference, entitled "Seeing Color / Printing Color."

"I am deeply honored," Prof. Lowengard says. "The APHA is the most important printing history association in America. I'm excited about it." Her talk, entitled, "Why color? On the uses, (misuses) and meanings of color in printing" comes out of a background founded as much in personal experience as in academic study. Prof. Lowengard, who says she has made dyes and pigments since she was a teenager, began her current career as an art conservator who specialized in textiles. "I found that all the questions I had when working with the object had to do with the history of technology and science and not about art history," she says. Her background gave her a unique perspective to her academic work. "The research I do as a historian is founded in what I have done all my life, but slightly better organized," she says with a laugh.

"I am deeply honored," Prof. Lowengard says. "The APHA is the most important printing history association in America. I'm excited about it." Her talk, entitled, "Why color? On the uses, (misuses) and meanings of color in printing" comes out of a background founded as much in personal experience as in academic study. Prof. Lowengard, who says she has made dyes and pigments since she was a teenager, began her current career as an art conservator who specialized in textiles. "I found that all the questions I had when working with the object had to do with the history of technology and science and not about art history," she says. Her background gave her a unique perspective to her academic work. "The research I do as a historian is founded in what I have done all my life, but slightly better organized," she says with a laugh.

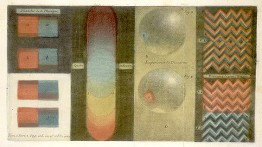

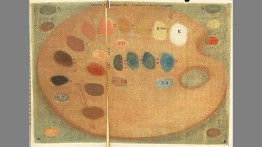

Those interests have led her to specialize in the history of color printing, most especially efforts made prior to 1795. "In 1795 Alois Senefelder, a German dramatist, received patents for his lithographic process, which exploited the incompatibility between oil and water and used stone slabs to print on paper," Prof. Lowengard says. "He did this to print music. The thing about lithography is that it is very quickly adapted into printing in color, the chormo-lithographic process. I write about everything that came before." This includes eccentric personalities like Jacques-Fabien Gautier d'Agoty, a printmaker of the mid-18th century motivated to develop a color theory to justify his printing methods. "Gautier thought Isaac Newton didn't know what he was talking about so he developed an entire theory of how the universe was formed in twelve colors," Prof. Lowengard says.

Professor Lowengard notes the parallels between her merged interests of engineering and art and those of The Cooper Union. "Printing in color involves a number of chemical, physical and aesthetic concerns," she says. "How do you get the ink to stick on the substrate? How do you make sure the colors work together chemically as well as visually? How do you keep the paper from shrinking in weird ways?" In her classes at The Cooper Union and in her keynote speech at the Grolier Club, Prof. Lowengard says she is "de-siloing." "It's taking the engineering of printing out of its silo and combining it with the art of printing. All of my work focuses on the issues around making something beautiful but lasting."