How to Build on a Warming Planet

POSTED ON: August 20, 2025

This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue of At Cooper magazine.

An Interview with Max G. Wolf CE’05 M.Eng’25

In 2005, Max Wolf walked across the Great Hall stage as class valedictorian, earning his bachelor’s in civil engineering, but he left The Cooper Union with one goal unfinished: a master’s thesis aimed at protecting Arctic habitat against rapidly rising temperatures. Nearly two decades after starting his research, Wolf returned last fall to Cooper with an ambitious new approach to slowing the collapse of polar sea ice, completing his master’s degree in May.

During those intervening years, Wolf established an impressive career dedicated to reducing the environmental impacts of building design, operations, and materials. He earned a master’s in architecture from Pratt Institute in 2008, gained professional licensure as both a structural engineer and an architect in New York State, and became a Certified Passive House Designer with the Passive House Institute. Wolf also advised on a recent landmark piece of climate legislation that sets limits on greenhouse gas emissions for New York City’s largest buildings.

What first sparked your interest in researching the built environment from an ecological perspective?

It happened in stages, but the first significant one occurred when I was happily engaged as a structural engineer at Werner Sobek in 2007. A colleague mentioned the Buckminster Fuller Challenge, and though I dismissed it from my mind as far-fetched, a few weeks later I came across a Planet Earth episode of a polar bear gracefully swimming far out into the open water of the Arctic Ocean alone, driven by hunger. The episode ends with the bear exhausted and wounded by a walrus and possibly dying. I couldn’t forget that bear, so I quickly developed a proposal for an array of artificial ice floes that progressed to the semi-finals.

As my research into climate change, site ecology, and allied topics continued, either on projects at work, like the Dubai Expo 2020 Sustainability Pavilion while I was with Grimshaw Architects, or on my own, I realized that sea ice is far too complex from micro to global scales to replace with the submersible platforms I proposed. For example, the yellow-brown ice algae that predominantly grows in the bottom few centimeters of sea ice contributes about 70 to 100 percent of the energy of a polar bear’s diet through intervening trophic levels (ice algae → zooplankton → fish → seals → polar bears). Similar levels of dependence exist for Atlantic walrus, polar cod, and ringed seals.

Why return to Cooper after accomplishing so much professionally?

I rejected finishing my thesis based on the Buckminster Fuller proposal when I realized it was insufficient. I didn’t need the degree for my work, so I decided to continue researching on the side until I came up with a solution that was as ecologically compatible and thorough as I could make it, while avoiding geoengineering methods due to their inherent risk.

I proceeded to earn an M.Arch while practicing structural engineering with the intention of transitioning into architecture, which eventually materialized with roles at Grimshaw and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). My long-term plan was to intertwine both professions in myself since they are so intertwined in nature. Around 2016, I conceived of a method to thicken and accelerate the production of natural sea ice using artificially induced rafting (layering and freeze-bonding the ice), which also maintains snow and pack ice topography, such as that found in and around pressure ridges, zones of elevated biodiversity that are declining in size and frequency. Once I was able to test the concept in a small ice towing tank, which took me about three years to design, build, and use, I approached Professor Cosmas Tzavelis, my original advisor at Cooper Union, about completing the thesis.

As eccentric as it may sound considering the conservative Western culture I was born into, I needed to find some solution for that swimming polar bear, and all the other animals of the Arctic pack ice that it symbolizes, even if it is merely a stopgap solution to possibly buy them a few more decades of time. It may be enough to get them to a long-term solution such as a combination of reduced emissions and solar radiation management like stratospheric aerosol injection. Writing the thesis helped me consolidate that effort, and prepare it for the next step, if there is one.

Two-thirds of New York City’s emissions come from its buildings. As a member of AIA’s Committee on the Environment (COTE), you reviewed the bill that became Local Law 97 (LL97), which targets an 80 percent reduction in emissions from buildings over 25,000 square feet by 2050. Can you explain that process and what its implications are?

That bill was Introduction 2153 of 2018, sponsored by Costa Constantinides, who is unfortunately no longer a member of the City Council. So, the original champion of the bill is gone, which I believe is contributing to mounting challenges to its implementation.

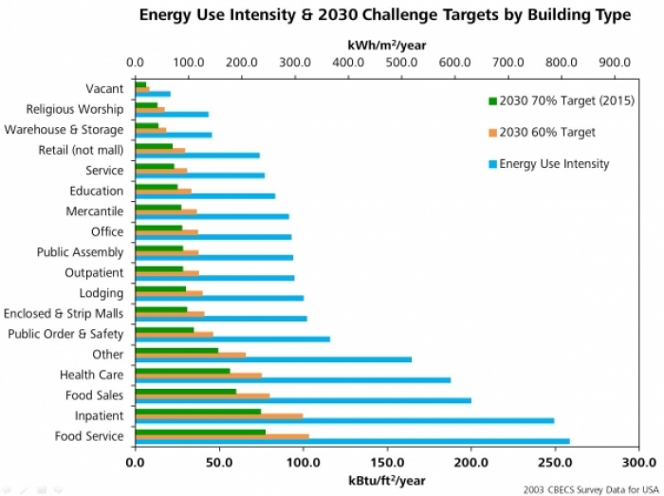

As far as considerations that went into AIA COTE Policy Committee’s review of the bill, one of the biggest that puzzled us for weeks was that it was based on emissions limits defined in terms of tCO2e/sf-yr (metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent per sq. ft. per year) rather than energy use intensity (EUI) that architects are accustomed to (kbtu/sf-yr). There was also no explanation for the values stated, for example a limit of 0.00846 tCO2e/sf-yr for occupancy group B (The entire business use group, which encompasses a huge range of EUIs). As I recall, neither Costa nor his staff would tell us how they were derived. It was strange. Eventually I was able to derive the bill’s 2050 target of 0.0014 tCO2e/sq-yr for all of NYC based on first principles and assuming an 80 percent emissions reduction based on a 2005 baseline, and then the particular values for individual occupancy groups became credible but were obviously Procrustean.

With that first hurdle mostly resolved, the other aspect that led the majority of COTE Policy members to eventually support the bill was that we were afraid it might be another ten years before a comparable bill came up for vote. I considered that given the rate of climate damage and that much of it is irreversible on the scale of human civilizations (hundreds to thousands of years), we didn’t have another ten years. There were other considerations, for example regarding exemptions and whether the $268 per metric tonne of CO2e fine was high enough, but those two dominated.

Regarding significance for the city, there should be many deep retrofit projects underway right now to meet the timeline of LL97, but the pace of retrofitting today is not significantly different than it has been in the last 25 years. I was told years ago by a political liaison that the bill passed not because it was the right thing to do, but because it promised to spur the growth of about 40,000 retrofit related jobs as part of a Green New Deal. It was certainly not passed because AIA NY supported it. I also suspect that since retrofits in the city have hardly begun, it has a weakened foundation to maintain support.

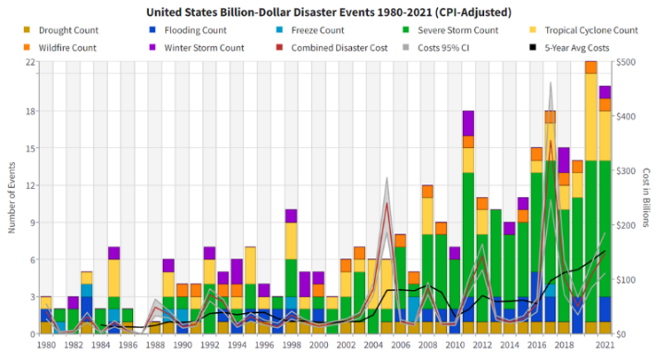

An example of recent pushback is Intro. 0772 of 2024, sponsored by a Council Member in eastern Queens seeking exemptions from LL97 for some of the residential building types of her constituents, along with the inclusion of open space in their building area calculations. Considering that this is on average a rather prosperous area of the city, if these New Yorkers are exempted from their fair share of reducing their emissions, who won’t be? Yet nearly fifty percent of City Council has already signed on to support it. Yes, it’s expensive to retrofit, but even a child can understand that the alternative is eventually far more costly, and there will be no undoing much of the damage: increasing deaths, injuries, and illnesses due to rising climate extremes; increasing property damage and insurance costs; eventual difficulty obtaining insurance; increasing taxes for repairs to infrastructure; taxes for sea walls, which have limited utility, and are expensive to maintain; higher property improvement loan rates due to added risk; and decreasing the attractiveness of New York City as a place to live and do business.

As Churchill observed, “You can always count on Americans to do the right thing—after they've tried everything else.” We are in the “try everything else” phase of LL97.

How do you think LL97 will reshape the way architects and engineers approach their work in the coming years?

I’m not sure. Thus far I’ve seen one sidestep LL97 by designing a large new building to current code, even though they knew the day it is granted its Certificate of Occupancy, it will be in violation of LL97. Politics, architecture, and engineering in NYC are typically dominated by short-term real estate interests. The Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) strongly opposed Intro. 2153.

Architects and engineers have essentially failed to significantly change their practices regarding emissions due to the extremely competitive market they operate in, and due to a lack of courage to speak the truth about the situation. I include my own efforts as a designer and environmental advocate in this failure. Without laws like LL97 to level the playing field of carbon performance for buildings and infrastructure, the pressure to realize projects with the least upfront financial cost to maximize short-term profit will always prevail. If you unilaterally decided to design only buildings that do their part to reduce emissions in conformance to LL97 and the Paris Agreement, you would quickly go out of business due to pushback from your clients and the current premium on low emissions construction. Low emissions buildings are not inherently more costly, as they achieve most of their reductions with cheap materials like insulation, sealant, air vapor barriers, and windows, and cities like Brussels that have implemented passive house as the code minimum have demonstrated this. However, since they are not yet the norm in New York City, they are still bid with premiums, which are to some extent “fear factors” that tend to price them out of existence.

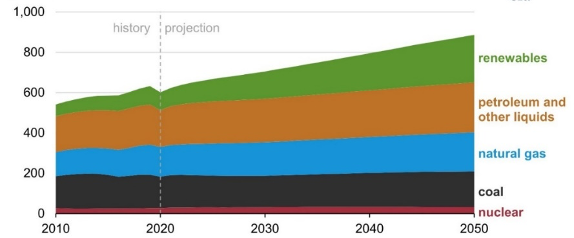

I suspect there is a 50-50 chance that LL97 will be either abandoned or so watered down with exemptions in the next few years that it will cease to be effective. In such a case, we will be failing in our duty as protectors of the biosphere we depend on for life itself, and we will deserve the derision and possible criminal prosecution of future generations if we live long enough. This goes in parallel with our lagging implementation of a green electrical grid, which Governor Hochul is in part responsible for. We need both to rapidly decarbonize: fully electric, high performance buildings which minimally load fully green grids. We will not reach 80x50 or carbon neutrality with just one or the other.

It should also be kept in mind that LL97 was always intended as just the start of what needs to happen in New York City to achieve a citywide 80 percent whole-life carbon emissions reduction. There needs to be a sister bill that requires an 80 percent emissions reduction of nearly all the buildings less than 25,000 square feet that LL97 doesn’t touch. There also needs to be a bill that requires limits on embodied carbon (whole-life carbon = operational carbon + embodied carbon).

Urban density is sometimes framed as affording greater efficiency, yet the growth of cities in recent decades also presents an enormous challenge in terms of addressing the drivers and impacts of climate change. What does the future of New York City look like to you? Beyond emissions compliance, what needs to change in how we design and build to decarbonize the urban environment?

Considering the shortsighted trajectory we collectively keep choosing to go along with: “business as usual” (what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change designates a “very high” emissions scenario, or SSP5-8.5), the climate of New York City will continue warming. The US is now the world’s largest producer of crude oil, with global extraction of oil and natural gas projected to continue expanding through 2050. This means more emissions, estimated to grow by around 25 percent. As a consequence, heatwaves will grow more deadly. Wildfires, urban fires, storms, and floods will grow more intense and frequent. Drought in the sunbelt and elsewhere will begin to destabilize food supplies and other commodities we take for granted. We have exceeded the 1.5°C limit which we pledged to uphold, will not stay below 2°C, and are probably headed for 3–4°C or more. Climate zones, along with people, animals, plants, and other species will be increasingly driven poleward and to higher elevations. The ongoing mass extinction that we are incurring will continue. Based on projected changes in freezing degree days and heating degree days, I have estimated that the climate zone of New York City will shift from 4A to 3A circa 2100—approximately that of present-day coastal North Carolina, though with more volatility. I’m sorry the data doesn’t point to something more hopeful.

I suspect all these trends will contribute to increased civil unrest in New York City and other large cities over the next few decades. They will probably also spur emigration, possibly leading to so-called urban doom loops. The accumulating severity of suffering may eventually unite progressives with young conservatives who already realize this is not a hoax against a common enemy, but that may be twenty years off, with a good deal of irreversible damage already done.

Ten years ago, I would never have said this due to its inherent danger, but I think we will need to implement some forms of geoengineering to stave off the worst of warming, for example with stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI). Based on a talk by an expert at the Arctic Repair 2025 conference that I took part in this year, SAI is probably 20 to 30 years away due to contentious politics and the need for development and deployment of the technology. Between now and circa 2050, localized or “targeted” approaches will probably be necessary, for example, using marine cloud brightening to keep coral reefs from being completely decimated.

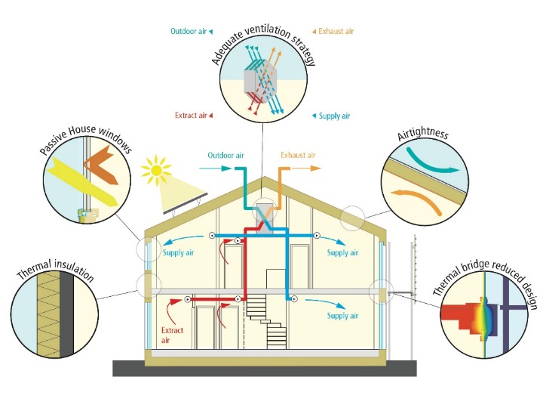

The best way to protect ourselves and future New Yorkers from these trends, and simultaneously reduce our emissions that are fueling them, is to implement widespread deep retrofits based on passive house principles while managing the embodied carbon to build them, along with rapid greening of the grid and the elimination of all fossil fuel combustion. For industrial processes that cannot be addressed with passive house design principles, e.g., flat glass manufacturing, a transition to all-electric processes is necessary. A few manufacturers I’m aware of are making progress in this area, and there has been a federal program to help all manufacturers reduce their fuel consumption and emissions.

You’re a Certified Passive House Designer and have taught courses on passive house (PH) construction. Could you share a little bit about its core principles?

It’s important to note that passive house principles apply to all conditioned buildings, not just houses, and they are essential to reaching emissions reduction targets of 60 to 80+ percent for many building use groups. The five core energy saving principles are:

- High airtightness;

- High levels of continuous thermal insulation;

- No significant thermal bridges;

- Very high performance windows and doors;

- Energy recovery of ventilation air.

Typical PH levels of insulation for New York City’s current climate are R-28 to R-48 for walls and R-60 to R-76 for roofs—well above current code. Recall that code is based on business and industry market forces and past disasters, so it currently takes no account of climate change or social inequities. High airtightness is in part needed to keep the highly insulated enclosure dry and prevent decay, either through fungus or corrosion. There are about 75 PH buildings in New York City, and about 6,000 in the world, the earliest dating back to around 1990.

Conservatives may be attracted to PH principles based on frugality, resilience, and energy independence, while progressives may admire the social equity benefits: a passive house building is more thermally stable and requires much less energy to condition, which means less risk of fuel poverty, interior spaces that are quieter, healthier (lower blood pressure, lower risk of extreme heat or cold), and conduciveness to calm focus, all of which contribute to lower medical bills and longer, more fulfilling lives. These are all aspects of New York housing that in general need improvement, especially as climate change worsens. For more in-depth background on low emissions enclosures and obstacles to their implementation, refer to High-Performance Façades: Barriers to Widespread Adoption by Façade Tectonics Institute.

Are there projects you’re especially proud to have been involved with?

I’ve pursued projects that support communities: residences, schools, R&D campuses, courthouses, hospitals… a water treatment plant in the Bronx; however, looking back on their generally poor emissions performance, I can’t say I’m proud at this point. Ambivalent and concerned would be more accurate. I contributed to the schematic design of the NY Climate Exchange being developed for Governor’s Island by SOM, which may end up achieving an 80 percent reduction in whole life emissions with respect to a 2005 baseline, which is what we need to achieve for all of New York City.

I would like to mention P.S. 62, the Kathleen Grimm School, even though I had nothing to do with its design or construction. I merely helped to problem-solve a few small issues during commissioning, but the school has an unassuming intelligence and beauty all its own: fully solar powered, sun-lit interiors, with a number of real-time building performance activities for kids to interact with. It happened because the School Construction Authority decided to make it happen and the city was willing to fund it. There is no reason why most schools in the US can’t be designed or retrofit to maximize their clean energy independence in a similar way. It’s also a concrete way for communities to demonstrate to their kid’s that they deeply care about their long term future. Climate anxiety is a growing problem for kids and young adults, and it won’t be cured with words or therapy.

What has it been like trying to bridge engineering and architecture in your work, given these fields tend to remain siloed by education, licensure, and research specialty?

Working alone, it’s great, but with teams it can be complicated. While training as an architect and structural engineer confers broad insight and skills for both, it can at times seem to elicit fear, suspicion, or skepticism from colleagues on either side. American architects and engineers can be like distrustful cats and dogs even under normal circumstances, let alone when there’s a self-described cat-dog in the room.

In any case, it has occasionally allowed me to do feasibility calculations for an innovative architectural, structural, or mechanical design (e.g., an atmospheric water harvesting device) that no other architect in the firm could do and that none of our consulting engineers were willing or able to do (risk aversion). While acting as the project architect, the mechanism could often be as simple as: “Here are my calcs for the design. If you can’t find a major error, this is what we’re doing.”

Is there any advice you’d give to a Cooper student who wants to work in building design, research, or engineering with the goal of creating a better climate future?

Be aware that your ability to contribute to designs that are truly sustainable will be extremely unlikely without laws like LL97 being enacted and enforced. Look for regions of the world that enforce such laws. A building is truly sustainable with respect to the carbon cycle at the heart of climate change if it doesn’t make climate change worse—that is, when it cuts its projected whole-life emissions by 80 percent or more with respect to a circa 2005 baseline. Population growth, which is often not accounted for, must also be factored in. This makes it difficult but not impossible. With fully green grids, it will be much easier but will still require careful design and just as careful construction administration to strictly limit whole-life carbon.

If a building or infrastructure project cannot achieve this carbon-based definition of true sustainability, it does not necessarily mean such projects should not be built. With respect to LL97, the 80 percent reduction in operational emissions is an average for all buildings, of which there are about one million in New York City. Hospitals that run 24/7 will for the present struggle to meet that target, but fortunately they form a very small percentage of gross floor area considering the whole city. A weighted average of all buildings can still achieve 80 percent as long as others, such as residences and offices, compensate for them.

If you are someone who sees intergenerational equity and the rights of nature as solemn or sacred duties that require decisive action, you may not be comfortable working in most architecture or engineering firms. In such a case, consider firms that only design according to PH principles or some analogous program, or consider pursuing research in some aspect of building science or materials science, for which you will likely need an advanced degree to contribute much to a team, or to do your own research. There is a good deal of important research in building physics being done at government labs such as NREL, ORNL, PNNL and LBL. Given the conflicted political climate in the US, finding stable employment in government funded research will at times be challenging, and competition for research jobs is intense.

Since low-emissions design codes are critical for fighting climate change, make sure you go out and vote for candidates who support them, and reject those who don’t.

Suggestions for those that want to go into practice:

- Become passive house certified via PHIUS or PHI, so you can analyze the thermal and whole life carbon performance of any design, and take part in a global support network.

- Teach yourself how to estimate the embodied carbon of different materials and assemblies using a spreadsheet. Understand the importance of durability in reducing embodied carbon. Learn how to read an environmental product declaration. Every project should have a whole-life carbon budget. The Inventory of Carbon and Energy (ICE) reference book is a good resource to start with.

- Learn THERM for 2D thermal modeling or assemblies (just a few hours to get up and running), and WUFI for 1D hygrothermal modeling if you’re attracted to enclosure design and building science. WUFI’s inner workings are rather complex, and ORNL offers a two-day seminar that is helpful.

- Always study the ecosystem you’re potentially building in: its history and projected future. Summarize indigenous cultural connections to ecosystem functions and native species.

- Since project service lives of 50 to 100 years are commonplace, every project should state in the specifications a range of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) that it is designed to operate in. It is irresponsible to leave this to chance. Teach yourself the basics of SSPs, how they will affect your project site, and how you and your team will future-proof your design.

- Close loops: Favor materials of low embodied carbon, low embodied water, high durability, that are either perpetually recyclable or biodegradable. Replace fossil fuel-based materials with bio-based. Favor fasteners over gluing. Always consider end of life, not to be gloomy but to improve the design. Your greatest legacy likely not be your buildings or structures, many of which will eventually be retrofit beyond recognition or demolished, but their waste streams, some of which will have effects for millennia. Work on the poetry of your waste streams. In wilderness, there is no waste.

- Minimize the surface-to-volume ratio of buildings and optimize solar orientation where possible. It is surprising how many architects ignore this, yet it is critical for low emissions.

- Have a dedicated space in your home for your personal research, including a small library. This can also help support you as you transition from job to job. Some of your most innovative projects may be those between jobs.

- Experiment with working at different firms and in different regions of the world.

- Become conversant in a few of the siloed specialties that encompass or underpin your areas of interest.

- Learn to better appreciate existing architecture and structures and their potential, as they are the key to leveling off the built environment’s contribution to climate change via deep retrofits. Modernism often thumbs its nose at past styles and building methods, but they typically are imbued with a good deal of practical wisdom that we often need to relearn (like window wall ratios below 40 percent). New buildings can be superficially exciting and glamorous, but will contribute little to nothing in the next few decades on a square footage basis to solving climate change. They may symbolize the way forward, but generally fail to come through regarding performance, and have inherently high embodied carbon.

- Consider the Rights of Nature, and the rights of nonhuman sentient beings in your designs. Based on the broad evidence from many fields supporting the evolution of all species from a common ancestor, nonhuman sentient beings have as much right to be here as we do. Caring for them and their ecosystems makes us better and more insightful human beings.

- Skim peer-reviewed journal articles in areas of your interest once a month (read at least the abstract, figures and conclusions). Thoroughly read at least one article every few months. If you have the budget, consider subscribing to a peer reviewed journal so that you are regularly reminded. As an example, I currently subscribe to Science (jargon laden) and New Scientist (plainspoken). The point is to keep learning the mechanisms of the natural world and acquaint yourself with the vast amount of research being done, written up by the people doing it—not journalists, bloggers or politicians. If you struggle to understand it, that’s normal, and part of the challenge of siloes. Siloes of specialization are naturally occurring and we need them, but we must also make an effort to spread their natural contraction or they can eventually throw our lives far out of balance. Spanning siloes is an essential part of being a competent architect or engineer.

- Attend and contribute to conferences. You may chance upon a kindred spirit from the other side of the globe, or improve your debating skills with those that disagree with you. Either can lead to breakthroughs in your work or opportunities. Yes, conferences can be inefficient and disappointing considering all the work needed to get a paper or work accepted, but it will likely improve the quality of your thinking and communication skills. If you exhibit a poster and are getting few questions, I suggest not standing next to it for the entire period. Rather, go ask others about their posters, and about half will then ask you about yours.

- Engage in physical activity regularly. Architecture and to a lesser extent engineering often demand long hours at a desk, yet breakthrough ideas often come during off hours, e.g. in the shower. Consider long walks for creativity (one of Nietzsche’s more practical observations), and for your long term physical and mental health. Do it alone, without a headset or other distractions, preferably in nature, and bring a small notebook or digital equivalent.

- Attend talks occasionally, for example at the Building Energy Exchange. Those sponsored by AIA or USGBC can be helpful and will earn you continuing education units for licensure, but are typically limited to conventional practice, which has failed to address its contribution to climate change ( about 40 percent of global emissions). LEED is practically useless for substantially reducing carbon emissions, and is in general a tool for marketing real estate. (In doubt? Check out some of the NYC building report cards for LEED buildings.)

- Experiment, maintain a growth mindset, and keep plodding! If you make an effort to contribute innovative ideas to address climate change, protect wilderness, or empower disadvantaged people, you are likely to encounter a sea of polite indifference, rejection, occasional ridicule or hostility. You likely will have moments bordering on hopelessness. Human cultures favor conformity and snap judgements, and always will since they require the least energy. The subcultures of architecture and engineering are no exceptions. Practice, patience, and persistence are the only antidotes that I know. Respect your ideas and intuitions, and keep a record of your work.