Building the (Near) Impossible: How Structure Becomes Architecture

POSTED ON: October 30, 2013

Jon Magnusson, the Chairman/C.E.O. of the structural/civil engineering firm of Magnusson Klemencic Associates, gave a free public lecture in the Great Hall that had a touch of magic to it. The lecture, entitled "Building the Impossible," showcased a series of impossible-seeming buildings designed by the likes of Rem Koolhaas and Frank Gehry that Mr. Magnusson's firm had helped make a reality. Throughout his presentation, which was part of an annual series sponsored by the Steel Institute of New York, Mr. Magnusson explored the ways "structure can become architecture."

In each case study Mr. Magnusson would present a baffling structural conundrum and then reveal the ingenious engineering that not only made it possible, but in many cases contributed to its realized shape. He began with Frank Gehry's design for the Experience Music Project building in Seattle, Washington. The Gehry studio initially presented a sketch resembling a child's squiggles and said, "this is a little far out for us," according to Mr. Magnusson. The final model had no straight lines. "We couldn't figure out what was a roof and what was a wall," Mr. Magnusson said. At the time there was no precedent for building such a structure.

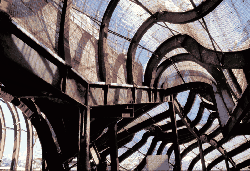

The steel ribs holding up the Experience Music Project building

The steel ribs holding up the Experience Music Project building

With the mystery set up, Mr. Magnusson revealed that a digital probe was run over the surface of the building's model to create X, Y and Z coordinates that defined the surface as a data set. "But that doesn't tell us how to hold the surface up," he said. In the end they looked to the human ribcage as inspiration for creating a set of continuously varying cast steel "ribs" that hold up the skin of the building. The result resembles something like undulating, metallic hills. "With the process we designed for the Experience Music Project we can do any shape now," Mr. Magnusson said.

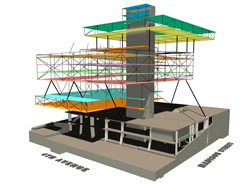

The hidden structure of the Seattle Central Library

The hidden structure of the Seattle Central Library

Introducing another building conundrum, Mr. Magnusson began, "As an engineer you know you are in trouble if the model requires the escalators to hold the building up." He referred to an early design of Rem Koolhaas' Seattle Central Library, which began as three platforms that seemed to hover in the air. Each "platform" housed a space for a separate function of the library: books, administration and public gatherings. Soon the architects draped a diamond pattern skin over the platforms that "presented tremendous challenges and tremendous opportunities," Mr. Magnusson said.

The exterior of the Seattle Central Library

The exterior of the Seattle Central Library

Once again he peeled back the steel curtain to reveal the structural engineering "magic." A system of columns and trusses supports the "gravity load" of the building, leaving the skin strictly as wind and seismic resistance. The central platform that holds all the books has the assembly platform suspended from it and the administrative platform cantilevered off of it. Then he revealed how the diamond-pattern skin holds another example of structure as architecture. Stress patterns on the skin required that some portions use two layers. "As you walk through the library and look at the double backing you can actually see the shape of the stress patterns," Mr. Magnusson said. "So the structure is not only what you get aesthetically … it's showing you how the structure is working."

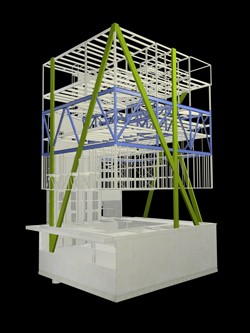

The strcuture of the Wyly Theater

The strcuture of the Wyly Theater

Another Rem Koolhaas project co-designed with Joshua Prince-Ramus, The Wyly Theater in Dallas, Texas, presented a new sort of structural challenge. "Most of the building doesn't exist at the ground floor," Mr Magnusson said. The designers wanted to open up the performance space so that the whole city could be used as backdrop. To accomplish this the architects designed the traditional front of the house be underneath the performance space and the back of the house to be above. Thus the performance space can be open on all sides. The other challenge: the designers didn't want any columns at the corners. Mr. Magnusson showed the audience the multiple iterations his firm presented in an effort to meet the architectural goals for the project while still being able to hold the building up. In the end he revealed a system of slanted columns that opened up 44-foot wide unobstructed views of the city from each side of the performance chamber. The result resembles a building suspended in midair.

Over the course of an hour Mr. Magnusson revealed a half dozen feats of structural engineering that make the seemingly impossible into a reality. Water tanks atop a needle-like 73-story apartment tower passively stabilize the building against wind gusts. Giant, retractable stadium roof panels weighing millions of pounds use pistons and hinges to allow for up to seven inches of expansion and contraction due to seasonal temperature change. Sliding bearings allow the roof of the San Jose International Airport to touch the ground at several points without fear of an earthquake tearing it down. In the end it was less a magic demonstration than an illustration of the crucial interplay of design and engineering. "The general public have no idea what's going on up there," he said. "Now you know."