Three Questions with Barry Bergdoll

POSTED ON: January 21, 2022

This spring, Barry Bergdoll, Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art at Columbia University, will be joining Cooper's Continuing Education faculty to teach a course entitled Design for Change: Architects of Modernity and Their Contemporary Resonance. We caught up with Professor Bergdoll, who is former chief curator of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, to learn more about the design and goals of the course.

The course you'll be teaching at Cooper is arranged thematically, not a traditional chronological approach. Why did you decide to take that approach?

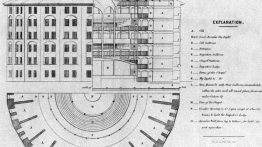

It is in fact both thematic and chronological... that is to say that each week moves us forward in time as we look at a major issue that was to be tackled by architects and planners about the nature of built space and then survey a historical period with a fast forward to our current situation. So, for instance, we look at issues of health and space and see the origins of the discourse on hospital space and its direct relation to public health in the 1770s and 80s before fast-forwarding to the theme of social distancing, which was a new vocabulary word for us all in 2020 but scarcely a new perception about the relationship of contagion to space.

The themes you've chosen are highly relevant to this moment, but you've also decided to include course sessions dedicated to individual architects. Why did you choose to highlight Gropius + Breuer, Bo Bardi, and Ambasz?

In each case the figure chosen is a major designer who one would study in any survey course on the development of modern architecture, or at least any one that had begun to take a more global geography as in the case of Lina Bo Bardi, an Italian woman who emigrated to Brazil and had a major impact on the world of architecture from her São Paulo base. Choosing a major figure lets us highlight their landmark contributions, but it also allows us to understand how a theme was worked on, elaborated, and refined by a single designer. I think it is inspiring to study a figure in relationship to a major preoccupation and a major set of challenges that gave coherence to their practice and to the relationship they had with their societies. I say societies in plural as several of the figures were emigres, including those you named.

What drew you to teach this course as a Continuing Education class as opposed to one, say, for undergraduate students?

I have been teaching undergraduates at Columbia for 35 years—as well as highly focused graduate students pursuing doctoral degrees. Part of the curriculum at Columbia College is a required course for all students in how to understand works of art and architecture, a course that allows them to develop skills for evaluating and appreciating works of art and also built spaces—buildings and cities, both those that exist and those that might be proposed. Here, art history and community engagement encounter one another, as the curriculum is based on the notion that having visual acuity is as important as a part of education as being able to critique arguments put forward in texts. It is exciting to work with young undergraduates who are surrounded by visual images and whose lives are impacted by architectural design but who have never before tried to find the words and concepts to engage with what surrounds them. So I am used to instilling those skills—and also, I hope, the enthusiasm for architecture that animates me personally—in students with no prior training. What draws me to Continuing Education is that here many of the participants in the course, the students, come from a longer life experience and bring that experience with its insights and questions to the discussion. The time we spend together at the end of the lecture to ponder the themes is the most exciting part of the Continuing Education program for me.