Design for Change: Architects of modernity and their contemporary resonance

Cost: $400.00

8 Wednesday Online Evening Sessions

March 2 to May 4, 2022

skipping Wednesday, March 16 and March 30

6:00 PM to 7:00 PM Eastern Time

Instructor: Barry Bergdoll

REGISTER ONLINE (Registration opens at 10 am January 4, 2022)

A Zoom meeting link will be sent to enrolled students 2 days before the start of the class by email.

A series of eight individual lectures on architects who sought to reform architecture radically for their time in ways that are still – or again – resonant today. The lecture course will cover a large sweep of time from the 1770s to the 1980s; but unlike a traditional historical survey course there is no attempt to sketch a narrative line of development. Rather each lecture will be a deep dive into a key issue from the long development of modern architecture since the 18th century accessed through the lens of a designer committed to tackling a larger issue for spatial design which might radiate reform through the society of the time. The episodes are chosen not only for their historical importance, but because they mirror many of the key issues such as health, ecology, public space, policing, the right to housing…. Each lecture will situate key architectural designs – both built works and influential unbuilt projects or ideal projections – in the political, social and economic context of its own historical moment as well as developing an analysis of the stakes of the designer’s work. Lectures will last approximately one hour with a chance for students to remain on line afterwards for questions and answers and discussion. It is expected that some of these questions will begin to tie together what is learned across the series. No prior knowledge of architectural history is necessary, although some familiarity with architectural terms is helpful. Although each lecture is focused on an individual name, the aim is to plunge students into an understanding of issues that were vigorously debated at a moment in the past and which will often sound contemporary to the issues 21st century societies are grappling with. Numerous other actors and designs will feature in each lecture alongside those of the named key figure.

The lectures are

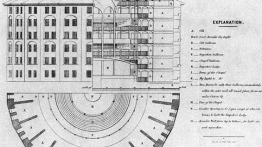

Session 1, Bernard Poyet: Incarceration and Disease: the 18th and 19th century Discourse on Institutions. The debate on the ideal form and function of the prison and of the hospital was a central preoccupation of European countries in particular in the final decades of the 18th century, with Paris and London taking leading roles in demanding both more humane but also more effective places for punishing criminality and curing disease. The French architect Poyet proposed some of the most influential designs based on a firm belief that a hospital or a prison was not simply a place to confine the sick or the criminal at a remove from society, but a spatial mechanism for reforming and curing. The debate on institutions in the years 1760-1840 was based on a rising belief that architectural design could change human behaviors. Observation of prisons in the young United States played a key role in the debates.

Session 2, Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc: Commemoration and Public Space: The 19th century invention of historic monuments and architectural restoration. Few architects are as connected with the invention of the modern concept of the historical monument as the French Gothic Revival theorist and architect Viollet-le-Duc. As debate has raged over how to restore the beloved cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris after the April 2019 fire destroyed not only the medieval roof timbers but Viollet-le-Duc’s spire, it is worth examining the role that the conservation and restoration of “monuments” played in crafting both cityscapes and national identities in the years 1830-1890.

Session 3, Henry Roberts: The right to housing: The emergence of the debate on worker’s housing is one of the key themes of architecture after 1850. The explosive growth of cities during the extended reign of the Industrial Revolution led not only to a massive migration of workers from the countryside to cities where they were often crowded into densely packed districts of sub-standard housing. It also led to a movement for reform of housing for the ‘laboring’ classes, spearheaded in Great Britain by philanthropic societies. Henry Roberts, whose project for an improved dwelling for working class families won much acclaim at the Great Exposition of 1851 in London’s Hyde Park (the first World’s Fair), was to make a lifetime specialty of designing such housing. He serves as the point of entry for considering the heated debates in the second half of the 19th century and opening decades of the 20th over whether or not the state had a duty to provide housing for the lower classes or whether the market might be created to interest other actors in improving housing conditions. At once a social and a hygienic issue, the debate over housing continues to this day.

Session 4, Frederick Law Olmsted: Parks and Public Space. Green space and public recreation were as much a part of urban reform movements in the 19th century as the call for better housing for working class citizens. With the creation of Central and Prospect Parks in New York and Brooklyn, and countless others across the United States and Canada, Olmsted made his name synonymous with the design and theory of green space for urban living. This lecture will study his designs and his writings on parks, but also the relationship of the work of one of America’s first landscape designers to the parks movements in other cities from Paris, London and Berlin to Mexico City.

Session 5, Natural Resources: Frank Lloyd Wright and the idea of organic architecture. Ideas of the relationship of architecture to nature are as old as written texts about architectural design, but they took on a particularly American resonance and ideology in the career of the architect whose name is often the only one that comes readily to almost anyone’s lips. Wright’s idea of the natural house remained constant even as his design vocabulary changed over the decades from his earliest houses in the 1890s to his final year of practice after World War II. But what does it mean to speak of an organic architecture, and what were Wright’s ideas about ecology?

Session 6, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer: Architecture and Technology since the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus was not only one of the most influential experiments in art and design education of the 20th century, it was also a key center for thinking about factory produced architectures. The great debates and experiments in pre-fabrication will be studied by tracing the careers of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and Bauhaus student Marcel Breuer as they moved from Weimar Germany via 1930s England to the United States. The question of whether or not factory production could create an architecture for a larger population rather than allowing architecture to be an architecture for the elite was at the core of this debate?

Session 7, Lina Bo Bardi: Public Space and Native Culture. Italo-Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi was not only one of the most innovative architects and designers of post-World War II Brazil, she was also one of the greatest advocates of an architecture of inclusivity, one that not only crafted spaces for public assembly, but which embraced at once the diverse popular traditions of Brazil’s diverse cultures (native, Afro-Brazilian, and European emigres).

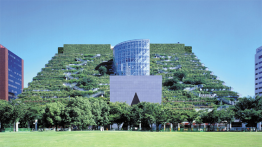

Session 8, Emilio Ambasz; Green over Gray and the architecture of Ecology. Argentine-born architect Emilio Ambasz first came to prominence with startling design exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in the 1970s, notably Italy: The New Domestic Landscape His architectural practice has been for nearly 50 years devoted to a commitment for reconciling architecture and nature, of embracing technology and ecology at the same time, of creating an approach of green over gray in an act of poetic redemption of mankind’s misuse of nature. His built works are few – most notably the Botanical Garden in San Antonio, Texas, and the ARCOS building in Fukuoka, Japan where a public park continues right to the roof of a towering building now celebrating its 25th birthday. As the future of life on a planet of human-induced climate change is the largest challenge facing this and future generations, Ambasz’s designs demand our attention.

Course Code: ArchHist1

Instructor(s): Barry Bergdoll