Turn the Night Into Day: The Photographs of Alfred Wertheimer

POSTED ON: December 20, 2010

Manhattan is a sensory overload. As any visitor knows, it is easy to be staggered by the canyons of man-made buildings, and the angry torrent of life that runs through it: there is an incessant, raucous din, the heavy smells, and the chaotic stream of sundry human lives, day in and day out. Manhattanis a living, breathing beast. It is this intense vitality that has made New York the muse of many of the 20th century’s great artists. It is a city that—love it or hate it—tows you in: and this is reflected in the work of generations of artists, from those like Charles Sheeler and Berenice Abbott, who celebrated its architectural feats as symbolic of progress, to those who recorded the price of modernity as reflected in the activities of its underworld, like Edward Hopper and Weegee. Almost everyone comes to New York to try their hand at success.

One day in 1956, a young man from the south came to New York to bring his music to a wider audience. This man, who was himself a force to be reckoned with, was as yet unknown outside of the south.He had come to play on Stage Show, a CBS program produced by brothers and big band leaders,Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey. A series of extraordinary photographs document this brief moment in time when the 21-year-old Elvis Presley was on the cusp of national stardom.

The photographer was Alfred Wertheimer, a young photojournalist, who had grown up in Brooklyn, and attended Cooper Union. He would go on to spend around ten days with Elvis over the next two years, and shoot roughly 2,500 photographs. The intimate photographs of Elvis are a product of Wertheimer’s artistic brilliance and the history of photography. Wertheimer managed to document pivotal moments in the creation of the new rock’n’roll that would take over the nation, in the vocabulary of an iconic movement in photography.

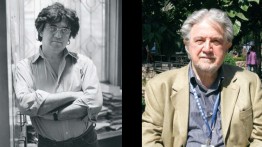

As Wertheimer tells it, there was a bit of luck involved too. Wertheimer, who looks two decades younger than his 81 years, moves around his office with a sprightly step and a shock of whitish grey hair. He likes to joke around, and he says that he only remembers two things: the day he met Elvis and today. Yet he seems to have an encyclopedic knowledge of a wide range of subjects.

In 1955, he was sharing a studio with a fewother photographers on Third Avenue in New York. Among these were Paul Schutzer,who had attended Cooper Union for a year, and Jerry Yulsman, who would go on to become a renowned photographers in their ownright. Schutzer’s grand dream in life was to be a staff photographer for Life magazine. He would drop any other assignment whenever Life gave him a call. As a result, he happily passedon any other work to his friend Wertheimer, which he would do in addition to his own assignments. And this meant that Wertheimer was in the right place at the right time to take on an assignment that would be the turning point of his life. On March 12th, 1956, the head of PR from RCA Victor, Anne Fulchino, called and asked if he could do a job the following week. “She says, I want you to photograph the Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey Stage Show,” Wertheimer says.

He was pleased, as Tommy Dorsey was one of his heroes. But then Fulchino told him that he wouldn’t actually be photographing Dorsey: “I want you to photograph Elvis Presley, who’s playing on Dorsey’s program.” He explains that there was a silence on his part before he said, “Elvis who?” Wertheimer accepted the assignment, and that was how he found himself in the same room as Elvis Presley, who was on the verge of becoming a national star.

He was pleased, as Tommy Dorsey was one of his heroes. But then Fulchino told him that he wouldn’t actually be photographing Dorsey: “I want you to photograph Elvis Presley, who’s playing on Dorsey’s program.” He explains that there was a silence on his part before he said, “Elvis who?” Wertheimer accepted the assignment, and that was how he found himself in the same room as Elvis Presley, who was on the verge of becoming a national star.

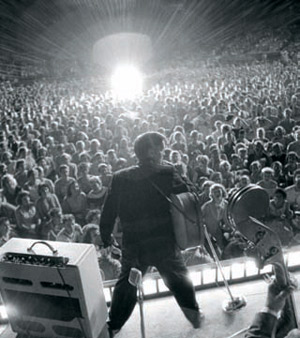

Wertheimer’s photographs show a pensive Elvis, just doing what he did: performing, spending time with his family or fans, napping, reading letters and papers,combing his hair, or listening to music. “From a photographer’s point of view,” he explains, “Elvis was unique in that he permitted closeness—not six to eight feet away, which was standard, but right up close, three to four feet away. He was so intensely involved with what he was doing: it was as if he were laser focused; whether he was combing his hair or chatting up the girls, he would be himself. I didn’t realize how unique that was.”He thinks about it for a minute, before adding, “I put him under my microscope and studied him, only my microscope was my camera lens.”This desire to document everyday habits and the details of life—to be a fly on the wall—are a long standing tradition in east coast American art. In fact, Wertheimer was taking a tried and true trope in photography—realism—and applying it to a new subject.

Realism, in Wertheimer’s hands, was not about the down-and-out, but instead about the up-and-coming. The 20th century marked a turning point for art in the United States. A focus on realism and the urban were the new thing. New York City’s art community in particular became enamored of realism. One influential movement of highly realistic art was created in Philadelphia in 1891 by artist Robert Henri, and included painters like John Sloan and Maurice Prendergast. This group would later be dubbed the Ash Can School of Painting, because their subject matter often depicted New York’s working class neighborhoods, and some of the grittier sides of life in the big city. Their images were often dark—not just in terms of subject matter, but quite literally in terms of tone. These painters found their subjects in poverty—prostitutes and drunks, life in the tenements. Above all, their subject matter was thoroughly urban.

By the 1930s, the New York School of Photography was nascent, though it truly came of age in the 1950s. The New York School took to the streets, often with small cameras and no flash, where it would catch life un-posed. Photography became poetic, a rendering of the drama of everyday lives; the photographers were witnesses, often unnoticed by their subjects, as they quickly and quietly took their shots. The artists who made up this movement reflected America’s ups and downs: the Great Depression, World War II, the post-war years, the wars in Asia, and the unrest of the 1960s and 1970s. It was a fertile period for art. Walker Evans, Helen Levitt and Weegee were all socially conscious exponents of straight photography. Later, heavyweights like Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, and Roy DeCarava (A’40) (among many others) emerged starting in the 1950s. These artists added the vocabulary of photography to their images. This meant that the very components of imagery itself—grain, darkness and lightness, focus and frame—became as important as the subject matter. They sought out the drama of the night, shooting in low light.

It was a fertile period for art. Walker Evans, Helen Levitt and Weegee were all socially conscious exponents of straight photography. Later, heavyweights like Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, and Roy DeCarava (A’40) (among many others) emerged starting in the 1950s. These artists added the vocabulary of photography to their images. This meant that the very components of imagery itself—grain, darkness and lightness, focus and frame—became as important as the subject matter. They sought out the drama of the night, shooting in low light.

“Different people come out at night,” says Wertheimer, who was deeply influenced by both the Ash Can School and the New York School. So he turned day into night, sleeping through the days, to start wandering and shooting at night. By the same token, though, the attention he paid to the denizens of the night brought them up as subjects of study, shining a symbolic light onto their activities. In effect, by turning day into night, Wertheimer also turned night into day.

The 20th century was a seminal time for music as well as art, and Elvis changed everything by bridging many different worlds. Leonard Bernstein once said that Elvis was the greatest social force of the century. “It’s a whole new social revolution,” he said. “The 60s come from it.” Elvis was a southern boy, raised by poor parents, who genuinely loved the blues music that he grew up with. He was able to bring what had customarily been black music to a white audience, by bringing the blues into mainstream rock ’n’ roll, transforming both forever. Elvis not only challenged America’s conservatism in terms of race, but in terms of sexuality. Many people disparaged Elvis’ highly sexualized act, as reviews in the New York Times and the Daily News showed. Ed Sullivan at first completely refused to have him on his show on CBS, until high ratings made him change his mind. Some, like Steve Allen on his NBCshow, tried to make Elvis tone the act down. No matter how much ire there was against Elvis, one thing was certain, young people—and particularly the girls—loved Elvis.

Perhaps they responded to the pulse of his rockabilly hits, or perhaps it was to his performances. But, first and foremost, he was an amazing artist, a talented singer who emoted genuinely. Wertheimer is convinced that what made Elvis different was the pure, raw emotion. “Elvis made the girls cry,” he explains. “This is not an easy task, especially with teenagers. To make them cry, that’s a talent that only somebody who was getting deep into their psyche would be able to get.”

Allof these ingredients can be found in Wertheimer’sphotos of Elvis.His photographs are witness to an incredible time in the history of photography, as well as to the birth of a star and new chapter in the history of music. He coined the term “available darkness” photography, to explain his philosophy that the darker the place, the easier to capture a person’s real nature. He used this technique to portray Elvis in a way that nobody did afterwards. And he was there for the performances that won the heart of America. Elvis was conscripted into the military in 1958, and Wertheimer was there to photograph him as he shipped out to Germany. After this, he never saw Elvis alive again. It wasn’t until almost 20 years later, upon the death of Elvis in 1977, that there would be a sudden surge in demand for Wertheimer’s photographs from this era. Wertheimer’s life didn’t stop with Elvis. He continued to freelance. Eleanor Roosevelt and Nina Simone were among the other people he subsequently photographed. He also spent a great deal of time as a cameraman for well-known programs like Granada’s The World in Action, and Mike Wadleigh’s film Woodstock.

Wertheimer’s life didn’t stop with Elvis. He continued to freelance. Eleanor Roosevelt and Nina Simone were among the other people he subsequently photographed. He also spent a great deal of time as a cameraman for well-known programs like Granada’s The World in Action, and Mike Wadleigh’s film Woodstock.

“You have all these experiences,” says Wertheimer, “and it becomes part of the collective memory. It takes a while to realize that your perspective is an important ingredient.” Alfred Wertheimer is represented by Govinda Gallery in Washington DC, Staley Wise in New York City, and Photokunst in Washington State. His work has been exhibited extensively and internationally. A Smithsonian Institution traveling exhibition of his photographs of Elvis, entitled Elvis at 21, began in January 2010, and will continue through May 2013.