How Seven Cooper Union Students Became the New Museum's Big Draw

POSTED ON: April 17, 2013

Art Club 2000, Untitled (Times Square/Gap Grunge 1), C-Print, 1992-1993

1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash, and No Star, a major exhibition at the New Museum on view through May 20, includes a number of Cooper Union-associated artists, though none more prominently than the collective known as Art Club 2000. The retrospective focuses on art made and exhibited in New York City over the course of the eponymous year. The work of Art Club 2000 appears as the echt expression of art at the time, promoting the exhibition on the catalog dust jacket, in the national print media ad campaign and even in New York City subway cars. Remarkably, Art Club 2000 members were still School of Art students when they made the body of work now on display.

The work, a series of photos of the members posing in clothing by the Gap, “points toward commercial advertising's ever-increasing influence on youth, as well as the reciprocal fetishization and obsession with youth culture that was so prevalent in society at the time” says Margot Norton, assistant curator of the 1993 exhibition. Both the exhibition and the work of Art Club 2000 has generated an abundance of media attention, including interviews and reviews in the New York Times, New York Magazine, Details, Artforum, ArtInfo, Art in America, Paper Magazine, and elsewhere.

Art Club 2000, which at the time included Daniel McDonald ('93), Patterson Beckwith (A'94), Sarah Rossiter (A'93), Craig Wadlin (A'94), Shannon Pultz (A'93), Gillian Haratani (A'93) and Sobian Spring (A'94), began as a group of friends who met studying at Cooper Union. Patterson Beckwith, who still lives in the same apartment he had as a student only two blocks from the Foundation Building, recalled, via email, the beginnings of Art Club 2000. "The (late) gallerist Colin DeLand was the dealer to some of our guest artists in sculpture (Mark Dion, Jessica Stockholder) and he was running an interesting gallery. He was interested in the idea of youth. [We] were invited to take part in a pedagogical exercise, and to mount a summer exhibition."

Art Club 2000, Untitled (Conrans I), 1992–93. C-print

Art Club 2000, Untitled (Conrans I), 1992–93. C-print

"At the time (it doesn't seem like a big deal today) it was remarkable that Matthew Barney was enjoying great success at the young age of 24," Beckwith writes. "We were all around 19, an age that made our exhibiting in a commercial gallery remarkable in itself. The process involved weekly meetings, (which were classes, with readings and discussion) and the group worked on consensus-building about what we might make. We made the work on our own; Colin was not there. Colin directed the process very closely though; we had to run things by him."

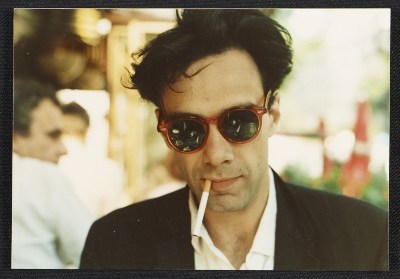

Colin de Land (from the archive of Peter Hopkins)

Colin de Land (from the archive of Peter Hopkins)

Colin de Land was the legendary downtown impresario behind the American Fine Arts gallery in SoHo. A visionary art dealer known for nurturing critically engaged and radical art that was often a tough sell in a market-driven gallery scene, de Land ran the much-admired gallery from 1986 until his early death, at age 47, in 2003. Through American Fine Arts, de Land became well known for being an early supporter and exhibitor of artists that are now as widely established as Richard Prince (with whom it was rumored he secretly co-authored art work under the name John Dogg), Cady Noland, Jessica Stockholder, and Alex Bag (another Cooper alumna, also in the 1993 exhibition). De Land admired and socialized with many of Cooper Union's art faculty, and it was Mark Dion who put him in contact with the members of Art Club 2000.

After a year of regular meetings with de Land, the group created Commingle, a show that drew inspiration and imagery not from art history but from a purveyor of affordable casual wear clothing: the Gap. The exhibit included purloined ephemera from Gap garbage bins such as corporate memos and inventory sheets. But the strongest work of the show has become a series of photos that Art Club 2000 staged. In each the group poses nonchalantly in Gap clothing (which they would return after photo shoots for a full refund) in private or public spaces. One image from the series that has been widely reproduced, for example, shows the group in Times Square. Some address the camera while others look away. None seem interested in much of anything. They all wear androgynous, identical outfits of the same baggy cut-off blue jeans, grey sweatshirts, oversized denim vests and red flannel bandannas: pre-made 90's slacker wear off the rack at the mall.

In an interview with Threaded, a blog on the Smithsonian's website, Patterson Beckwith describes the time when the Gap "had just opened 20 locations in Manhattan and there were loads of ads in bus shelters [the Individuals of Style campaign of the 1980s showcased actors, musicians, and other creative types in Gap clothes] —it was kind of in your face and we were responding to that.”

Art Club 2000 members and other students with Professor Doug Ashford (in hat). Photo by Soibian Spring and Will Rollins

Art Club 2000 members and other students with Professor Doug Ashford (in hat). Photo by Soibian Spring and Will Rollins

But it was more than just a sardonic look at a national mid-market brand. “There was this idea of having a critique of institutional critique,” Daniel McDonald and Beckwith recently told David Valesco on Artforum.com. The Gap represented a symbol “beneath [artistic] contempt… not a serious subject, like HIV prevention or gentrification, subjects that we were criticized for not picking up on. We chose the Gap because it represented nothing: a gap.” Institutional critique in art has traditionally focused on examining the operational patterns and political role of art institutions and markets, and it has deep roots in the pedagogy of the Cooper Union School of Art. One of the most prominent living figures of institional critique, the German artist Hans Haacke, taught generations of Cooper students from 1967 through 2002, including most of the Art Club 2000 members.

"The School of Art has a long legacy of encouraging students to conceive of alternative modes of cultural production," Saskia Bos, Dean of the School of Art says. "Working in a collective, like Art Club 2000 or the Bruce High Quality Foundation [Cooper alums who are having a solo retrospective at Brooklyn Museum starting in June], challenges conventional notions of authorship and suggests agency. Cooper Union School of Art students often see their practice either as having an impact on existing culture or an attempt to imagine something different."

Professor Doug Ashford, who taught nearly all of the Art Club 2000 members, recalls them, fondly, as having a “perverse” approach to making art. “It was an expression of the need to turn the world on its head,” Ashford explains. The Art Club 2000 members, he says, “were using themselves and their own cultural condition as young bodies in their work. This was a very critical kind of self-reflexivity. The photos up now at the New Museum display the degree of self-commodification they embraced. This was something very astute given the way that commodity culture was being re-organized through the artworld and around a particularly distorted sense of youth.”

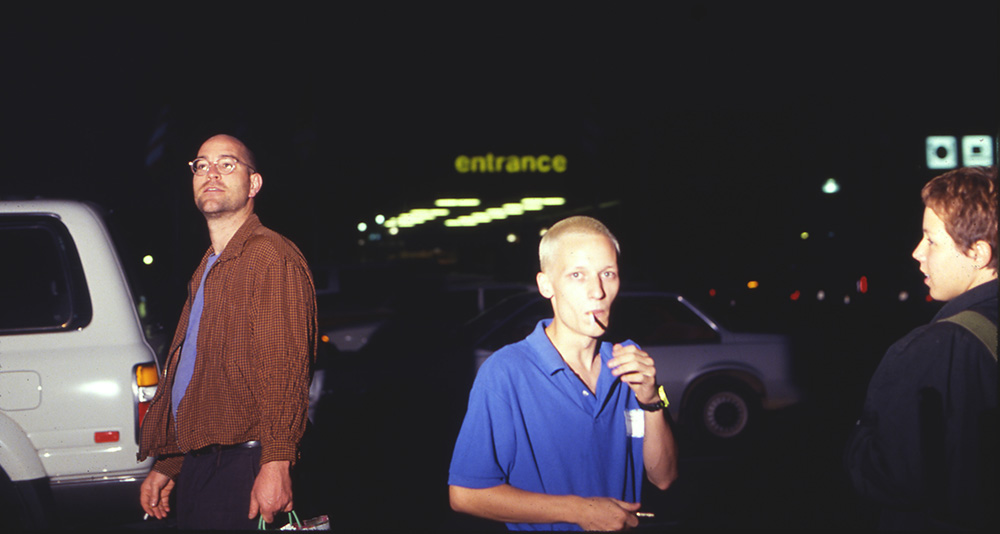

Professor Doug Ashford (left) with Patterson Beckwith and Jen Budney at a Newark Ikea for an in-store performance created for one of Ashford's classes

Professor Doug Ashford (left) with Patterson Beckwith and Jen Budney at a Newark Ikea for an in-store performance created for one of Ashford's classes

Though Art Club 2000 have not officially disbanded, they have been inactive for a number of years. We asked Mr. Beckwith, who teaches photography full-time at the City College of New York in Harlem, about his feelings seeing his work of twenty years ago in the New Museum. "I'm very pleased," he wrote. "As with any large group show, the work is a bit out of it's context - the photos were part of a much larger project. That's the nature of the show though."

Patterson Beckwith in 2013. Photo courtesy Patterson Beckwith

Patterson Beckwith in 2013. Photo courtesy Patterson Beckwith

Does he see the use of the Gap photos as actual advertisments perverting their artistic intent? "No," he writes. "If anything that was the spirit in which we made the image. We were a kind of a 'pose band' and talked about modeling our time through the photos; we were meant to be acting as 'generational spokesmodels.' In any case the images were always meant to be reproduced. And though the group worked for many more years on plenty of other projects, the photos at the New Museum are what seems to have had the most staying power; they continue to have some traction as images. They represent the group, and are a starting point for a conversation about what we did."

And how does it feel to see his youthful self on the subway? "Rad!" he writes.