"WOUND" Offers Space for Collaboration

POSTED ON: October 12, 2016

On October 13, the exhibition WOUND: mending time and attention opens at the 41 Cooper Gallery. Conceived of and designed by Caroline Woolard and curated by Associate Dean Stamatina Gregory, the study center addresses the ever-greater disciplining of time and the social and psychic toll that exacts on collaboration. “If most New Yorkers have no experiences of democracy at work, at home, in school, or online, how will we learn to work together? This study center provides a practice space for joint work and joint decision making.” Dean Gregory notes that the exhibition “highlights the work of artists and collectives who have committed to practices of collaboration.”

Ms. Woolard, a 2007 graduate of the School of Art, points out that just as dancers continue to train by taking classes throughout their careers, so artists need a physical “space for group work in the visual arts,” she says. To that end, WOUND aims to provide that space as well as a study center for readings and what she calls “sculptural tools.” These last are different objects used to promote group work, ones that puncture the notion that any one object can exist autonomously. Visitors may check them out for use within the study center. In addition, trainings that promote listening, attention and collaboration are organized for sessions throughout the run of the exhibition. Most importantly, Woolard argues that WOUND, though only a month long, will demonstrate that a permanent space is needed for honing these practices.

Ms. Woolard talked to us about Wound and spoke about why the contemporary regimentation of time often keeps us from cultivating the skills needed for collaborative work, including attentiveness and deep listening. Additionally, Dean Gregory points out, “It’s important to remember that Wound isn’t about providing ameliorative practices that enable us to cope with the imposition of neoliberal constraints, but to develop the basis for practices of resistance. Resistance demands collectivity.”

What is WOUND?

Wound is a study center for practices of listening, attention, and collaboration. In its month-long installment at The Cooper Union, we (curator Stamatina Gregory and I) worked together to select tools from artists and collectives whose multi-year practices register in the visual arts. In its online archive, WOUND will present a full spectrum of tools, facilitators, and practices from the performing arts, speculative design, community organizing, geography and engineering.

I call WOUND, “a study center for the mending of time and attention.” WOUND makes a double claim on meaning. As the past participle of the verb to wind, “wound” reaches back to a past that has seemingly been set in motion. And yet, as a present participle of the same verb, for example “the clock is wound,” the verb indicates a potentiality that can be altered, it indexes a conclusion that is not foregone. Nonetheless, when most visitors first see the word W-O-U-N-D, they will make an association to the much more common noun form: a wound as in a harm or an injury.

What is the relationship between time (or the disciplining of time) and attention/listening? How is time connected to political engagement and activism?

Listening and looking are forms of artistic attention. Collaboration requires both. What kinds of listening and looking are provoked by contemporary artworks? How can we develop capacities of listening and looking that enable us to become more nuanced critics and practitioners of collaborative work? WOUND starts with the premise that certain practices and tools can offer an experience of collaborative time; a time, which is specifically marked by our engagement with one another.

Many of the practices presented in this study center acknowledge the deep hurt, or wounds, from which political action, artistic collaboration, and transformative organizing often begin. Ultra-red’s protocols emerged from HIV/AIDS organizing; Sick Time with Canaries’ practices from a support group for artists with autoimmune diseases; Danica Phelps’ work from precarity; taisha paggett and Ashley Hunt’s practice from the epidemic of mass incarceration; Shaun Leonardo’s I can’t breathe from mass police-sanctioned violence against communities of color. These artists and groups’ practices are life long, acknowledging that wounds cannot be healed within the temporality offered by conventional institutions.

Why is time a critical subject?

Perhaps the current injury on view at Wound is in thinking that time has been wound against our desires: there is “too little time”; that time moves “too quickly”; that our time has been attenuated. WOUND asks: How through collaboration can we unwind time in order to render it open, unspecified, and inviting? How can we recognize the nature of seemingly dwindling attention not as the result of being “wound up,” but as the result of being hurt or injured, an emotional claim which, necessarily, implies the ability to be healed? Can these practices render time a qualitative, not quantitative, phenomenon, something that is marked and construed for groups through mutuality rather than received through authority?

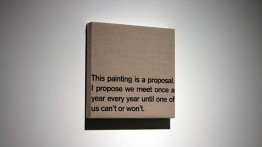

To embody collaborative time, groups must learn how to gather, how to need and support one another and how to tremble together. Dave McKenzie proposes that we “meet until we can’t, or won’t.” Chloe Bass measures the spatial distance of discomfort. Judith Leeman creates tools for nonverbal communication. The Order of the Third Bird and Project 404 build a musculature for sustained attention. Yoko Ono asks us to speak with questions only. Paul Ryan invites us to identify the subject-positions from which we interact. Linda Montano directs our gaze. Adelheid Mers provides a path for the drawings that often accompany dialog. The Extrapolation Factory builds a context in which imagining the future helps us to better understand the present.

Instruments for measuring time have been essential in advancing most kinds of technology. They’ve also been applied to our bodies – efficiency studies, work schedules, etc. Is the goal of WOUND,or one of the goals, to look at the ways artists work with time?

Time-keeping devices are always time-producing devices as well. Rather than understanding time as divisible, linear, and disciplinary, as seen in the historical clocks and watchmaker’s tools from the National Watch and Clock Museum and the books on view from the New York Historical Society, the center studies how artists produce time through collaboration.

This study center makes impossible the fantasy of an autonomous object, removed from collective practice and historical context. Every object in the study center is called a tool, and is either "on view" or "in use" in trainings by collectives and politically engaged artists. WOUND links a wide range of collaborative and participatory practices, from the so-called 1960s dematerialization of the art object (tool on view: Yoko Ono), to 1970s cybernetic systems (tool on view: Paul Ryan), to 1980s feminist durational performances (Linda Montano), to HIV/AIDS activism of the 1990s (tool in use: Ultra-red).

Practice requires duration. Art departments and institutions have increased funding for social practice since the early 2000s, but the communities that are generated within academic and non-profit spaces tend to be short-lived and outcome-oriented. Transformative practices cannot be developed or contained in a month-long exhibition, a four-year or two-year degree, or a year-long grant. Just as dancers take classes throughout their lives, WOUND aims to become a permanent practice space for group work in the visual arts. To move toward an aesthetic of practice, further study is required.

Where will the study center go next?

We are looking for a permanent location. For inquiries regarding traveling the study center’s collection, or to offer a space to WOUND, please email Caroline Woolard at caroline@woundstudycenter.com.