Local Infrastructures for Global Systems: Containerization and the Alameda Corridor

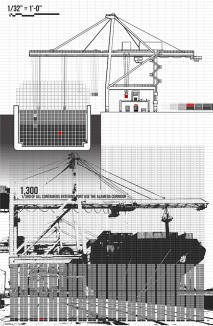

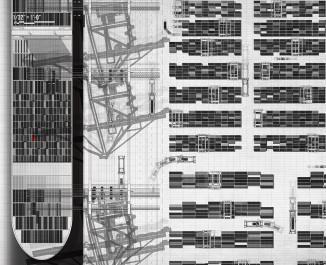

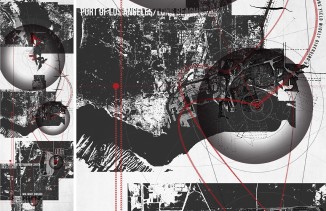

The Alameda Corridor is a 20 mile long, 55 foot wide and 33 foot deep railway trench that connects the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach to the national railway network. The corridor handles about one third of all shipping container traffic that enters the two ports, most of which comes from China. Accordingly, it would not be an exaggeration at all to say that the Alameda Corridor is central to everyday capitalism in the United States.

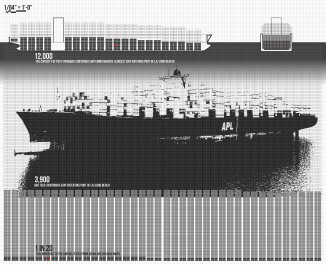

To demonstrate the Alameda Corridor’s global resonance, this project traces the journey of a single t-shirt -- based on relative scales of time, money and distance -- from its production in the Ready-Made Garment district of Dhaka, Bangladesh to its consumption in a Wal-Mart store outside of Chicago, Illinois. The t-shirt, which is produced for about $3.00 and travels by truck, train, cargo vessel, crane, and forklift before arriving at its destination half way around the world where it will sell for under $10.

Ultimately, in following the t-shirt from production to consumption, this project reveals the mechanized underbelly of the global economy: a logistics system so intricately coordinated that even the most minor changes to its structure: re-designs of shipping vessels, delays in delivery, shortages in raw materials, and so on, can trigger drastic ebbs and flows in all ends of system. Otherwise known as the Butterfly Effect, the smallest alteration to shipping methods in China, for instance, could mean total closures to ports, railways, and stores in the US and elsewhere. For some industries, the daily precision of this system means the difference between financial solvency and total bankruptcy. The drawings, then, make visible the time, movement and mechanics of a clock-work network which, despite its physical presence, functions greatest when it proceeds unnoticed and invisibly.