Look Closer

POSTED ON: November 17, 2017

Though it is only her first semester teaching at The Cooper Union, Annika Finne, adjunct instructor, seems to have hit on something big. The class she proposed and now teaches, "Reading Surfaces: Painting Techniques Over Time," taught as an art history course through the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, quickly reached maximum capacity. It examines, "histories of artists’ materials, tools and techniques as they play out on the surfaces of Western as well as Ethiopian, Persian, and Latin American paintings c.1300-1800," according to the course description. In the hands of Finne, who is a paintings conservator and is earning her PhD in art history, that plays out as a class of field trips to view world-class painting collections. Students practice investigative techniques through close visual examination and attempt to re-enact the processes used by the artist to construct the work. From that investigation, they consider how those materials and techniques interact with the content they present. It hits a sweet spot of artistic processes with art history and the practice of close observation.

"I was the first one to sign up," Johnathan Wilborn, a sophomore in the School of Art (like all the other members of the class), says. He was eager to broaden and challenge his own practices by examining the works of the past. "It's fantastic. I love it. It breaks the fourth wall and makes painting accessible. I am learning more about my own craft. The class relates to other courses. There is nothing like it that I have encountered."

We tagged along for a trip to the Northern European Art galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see how the class works. Professor Finne takes the first half of the twenty students upstairs at 10:10 am. She draws them in front of a work, starting with Jan Van Goyen's "Castle by a River" (1647), and asks them to silently examine it for a few minutes. She then asks a series of prompts: "What is the support?" "What color is the ground?" "How can you tell?" and "What does that do?" The Van Goyen, for example, is painted on wood, the natural grain of which can be observed running horizontally across the work thanks to the thin paint layers. Further, the color of the wood comes through, particularly in certain spots, lending them a warm brown tone. Dutch painters at the time were interested in how a painted image of the world relates to the physical world, Finne mentions, and "this painting tells us what the painting is made of."

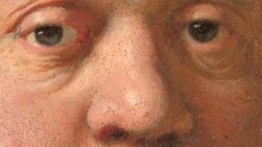

The interaction with each of the half dozen other works over the next hour are similar. A Frans Hals "Portrait of a Man," painted ca. 1636-38, has a light brown ground color, observable around the rim of his black hat. His chin is defined by a black line that does not perfectly align with the flesh. Professor Finne says this indicates that the work was not done alla prima, in one go, but since the paint that comprises the line does not blend into the paint beneath it, it had to have been applied after it had dried, implying a conscious revisiting of the work. Further, the deliberately imperfect line declares: "this is a painting." Hals does not try to make a rigorous, mirror-like likeness. Elsewhere the students closely compare two noses on contemporaneous portraits by Rembrandt. On one a thicker layer of paint has been manipulated into a subtle texture that resembles pores. The paint essentially is physically like the subject's skin as opposed to a painting of it, Finne points out. Throughout the students offer their own thoughts on the process based on their own experiences, extrapolating meaning behind those choices.

"I am so enjoying working with these students," Finne says. "Because they are practicing artists they are very comfortable with this idea that a painting is a physical object and therefore a series of physical actions is necessary to produce that object. There is no detachment or fear of the painting. The Cooper students are very talented at re-imagining how the thing was made. Talking about techniques is a point of intersection for many different fields. And so, they are intensely curious about those directions these intersections open, from the degradation mechanisms that pigments can experience over time to the current lighting conditions of the work."

Final projects include both a 1000-word observation of materials and techniques of a single work, and how they inform the meaning of the work, along with a more free-form "reaction" to that. One student plans on examining the physical human costs necessary to mine a certain blue pigment from Afghanistan while another may attempt a re-creation of part of a painting and write about successes and failures of that experiment.

"You can get very far with just looking," Finne says.