I Resist!

POSTED ON: March 28, 2017

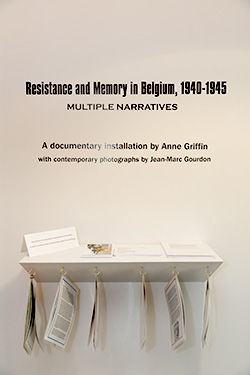

An exhibition that first appeared at The Cooper Union in 2005 and now has been re-mounted at Queens College takes on a new resonance in the current political climate as it examines the role of Belgian resistance to Nazi occupation during World War II. Professor Anne Griffin of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences originally put together "Resistance and Memory in Belgium 1940 – 1945: Multiple Narratives," at the suggestion of a fellow Cooper Union professor who saw in her research a captivating large-scale presentation. Since then the exhibition has travelled to Yeshiva University and to Amsterdam, and then after a trip to a Quaker academy in Locust Valley, NY, has now settled into the Queens College Art Center, on the sixth floor of the Rosenthal Library until May 26.

In a cylindrical sun-drenched space a visitor is presented with a series of 30-inch photographic portraits taken in the early 2000s of some of the surviving men and women of the underground Belgian resistance to Nazi occupation. Alongside each portrait is a photo of that person from the time of the war taken from identification papers, street photographers or personal snapshots, blown up to match the scale of the contemporary images. A wall text accompanies each portrait, featuring a translated statement from that person's oral history.

In a cylindrical sun-drenched space a visitor is presented with a series of 30-inch photographic portraits taken in the early 2000s of some of the surviving men and women of the underground Belgian resistance to Nazi occupation. Alongside each portrait is a photo of that person from the time of the war taken from identification papers, street photographers or personal snapshots, blown up to match the scale of the contemporary images. A wall text accompanies each portrait, featuring a translated statement from that person's oral history.

"I've chosen to call this a documentary installation because it's based on the photographic and testimonial record of a group of resisters and also because it has a certain narrative coherence," Professor Griffin says. "These are all people I have known and some of them I have loved very much. Some of them are remarkable people who have been an illumination. I felt my role was to give them voice and transmit their stories to future generations."

Currently teaching courses in the core curriculum as well as public policy and the politics of collective memory, Professor Griffin has been a member of The Cooper Union faculty since 1978. After having been introduced to some of the surviving Belgian resistors she received a Fulbright to do further research there. A French friend, Jean-Marc Gourdon, offered to take their photos as part of the work, later leading to the exhibition in 2005.

"At the time it went up at Cooper Union I really only saw one narrative," Professor Griffin says. "But over the years, when I did gallery talks, I found that I ended up doing something different each time. So, for this iteration I thought maybe we should have multiple narratives: Resistance Across Borders, Resistance in Flanders, Escape and Evasion Networks, Intelligence Services, Belgium's Jews in the Resistance and Moral Courage." Color-coded shields accompany each image, corresponding to one of the six different narrative themes that Professor Griffin organized. Portable laminated cards offered at the entrance provide visitors a self-guided tour of each theme.

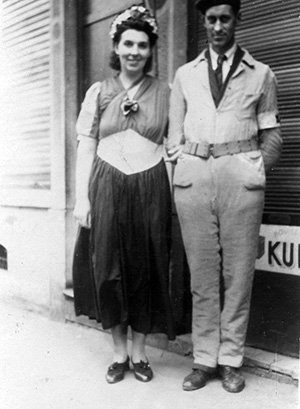

If one is fortunate enough to follow the professor around the gallery you get a taste of her passion for the individuals and their remarkable stories. One historical photo, at right, shows Arthurine Hembise and her husband Raymond beaming with pride in a picture taken right after the liberation. She wears a homemade dress and tiara. He wears the uniform of the Secret Army. "She was a farmer," the professor tells you. "They would house members of the Secret Army. She carved out a hole underneath the manger in the barn to stock arms. They would go out at night and these containers would be flown from England and dropped by parachute. She later used the parachutes as material to make the dress she wears, in the colors of the Belgian flag. Years later she still had the dress."

If one is fortunate enough to follow the professor around the gallery you get a taste of her passion for the individuals and their remarkable stories. One historical photo, at right, shows Arthurine Hembise and her husband Raymond beaming with pride in a picture taken right after the liberation. She wears a homemade dress and tiara. He wears the uniform of the Secret Army. "She was a farmer," the professor tells you. "They would house members of the Secret Army. She carved out a hole underneath the manger in the barn to stock arms. They would go out at night and these containers would be flown from England and dropped by parachute. She later used the parachutes as material to make the dress she wears, in the colors of the Belgian flag. Years later she still had the dress."

The space is reflective, both literally and contemplatively. The glass covering the photos not only catches you looking, but, because of the curved interior, many of the other individual's portraits as well. "The reflections are an asset to this installation because so many of them knew each other. For example," the professor says as she points to two portraits, "he had a crush on her." She moves across the room and points to two others that catch each other's reflection. "And this one here, he was her chief." The woman, Andrée Antoine Dumon, was, among other resistance roles, an agent of what became known as Comète, a network of safe houses that shuttled downed allied pilots south, over the Pyrenees into Spain and on to Gibraltar to be repatriated.

One of Professor Griffin's favorite images, the one that has been used as the poster for the exhibition, shows Andrée Geulen, a young woman facing the camera in mid-stride as she walks down the sidewalk. Ominously a German officer walks a few paces behind her. She was on her way to rescue a Jewish brother and sister. "It shows her at the moment she was snapped by a street photographer, which were very common. But in Belgium, many of them were working for the Germans. She knew that. She also knew that every Friday morning, the Germans would rent a movie theatre where they would show the faces of people they were looking to arrest. At this moment, she realizes that her picture is being taken. There is no fear on her face. It's anger. Her job was rescuing Jewish children. She was recruited for it because she was a blond, blue-eyed exemplar of so-called 'Aryan' beauty. The photographer gave her a ticket and her chief told her she must get that photo and the negative. So she did, before the Germans could get to it."

One of Professor Griffin's favorite images, the one that has been used as the poster for the exhibition, shows Andrée Geulen, a young woman facing the camera in mid-stride as she walks down the sidewalk. Ominously a German officer walks a few paces behind her. She was on her way to rescue a Jewish brother and sister. "It shows her at the moment she was snapped by a street photographer, which were very common. But in Belgium, many of them were working for the Germans. She knew that. She also knew that every Friday morning, the Germans would rent a movie theatre where they would show the faces of people they were looking to arrest. At this moment, she realizes that her picture is being taken. There is no fear on her face. It's anger. Her job was rescuing Jewish children. She was recruited for it because she was a blond, blue-eyed exemplar of so-called 'Aryan' beauty. The photographer gave her a ticket and her chief told her she must get that photo and the negative. So she did, before the Germans could get to it."

While the exhibition was planned more than a year ago, a show about social and political resistance takes on a certain resonance in the current domestic political climate. Professor Griffin loves the timing. "Kant poses some questions: What can I know? What must I do? What can I hope? These are the questions people were asking themselves at that time. And these are the questions people are asking themselves today. The resisters knew very little about what the outcome would be, particularly at the time they made their choice. The chances for an Allied victory were far from clear at the time; in fact, the German victory seemed almost definitive. Yet they chose to follow their conscience. They had hope, and they not only acted on that hope but kept it alive in others."