Cooper Union Quickly Convenes "Teach-in" on Preparing Cities for the Next Storm

POSTED ON: November 16, 2012

From left: Jody Grapes, Atina Grossmann, Kevin Bone, Susannah Drake, Albert Appleton

A mere two weeks after "superstorm" Sandy devastated the New York and New Jersey coasts, and one week after re-opening its doors, Cooper Union’s academic community convened a “teach-in” in the Great Hall to discuss the infrastructure challenges that remain. Sandy created billions of dollars of damage, according to the latest estimates. Lower Manhattan, and Cooper Union, fell into darkness for five days. With power restored, Cooper’s central place in the city, as well as its special combination of art, architecture and engineering talents, made it a natural place to convene an ad-hoc discussion on crisis, cities, weather, disaster preparedness, and the future of New Yorks' infrastructure.

Organized by Dean William Germano of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences and moderated by Professor of History Atina Grossmann, the two-hour event began with a panel discussion that included members of the faculty and staff. Professor of History Peter Buckley put Sandy into historical perspective. He reminded the audience that storms in Manhattan—though increasingly influenced by global warming and rising sea levels—are nothing new. As terrible as it was, Sandy was one instance of a persistent threat, Professor Buckley explained, and better preparation with more careful urban development would steel the city against this kind of recurring natural disaster.

Jody Grapes, Director of Buildings and Grounds, joined in for a recollection of more recent events: how Cooper’s Emergency Management Team responded to Sandy and ensured that students, faculty, staff, as well as Cooper’s buildings, remained safe throughout the storm. Dean of Athletics Stephen Baker commended the Cooper community in their activist response to the storm. “Cooper Union may have been plunged into darkness last week,” Baker said, “but we are an institution that is never powerless.”

A triumvirate of faculty from the Institute for Sustainable Design followed with a more critical perspective on the way urban planners, policy makers, developers, and architects can create (or mitigate) precarious conditions in urban contexts. Director Kevin Bone focused on the economics of disaster and city planning, arguing that the recent boom of development and technological advancement has, besides making the city larger, increased the value of its infrastructure. Such growth creates a risky situation for New York in particular, Bone says, as the larger and more costly city paired with a public resistance to taxes encourages shoddy infrastructure and bad policy.

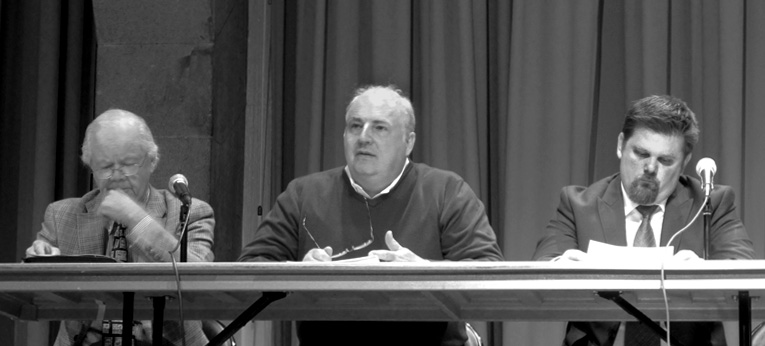

From left: Dean Stephen Baker, Professor Peter Buckley, Jody Grapes

Susannah Drake, a visiting Professor of Architecture, elaborated on the increased threat of rising sea currents and her own work, which she described as focused on “how cities can have a more reciprocal relationship with the environment.” She described a 2010 project in which her design firm, dlandstudio, created a plan to increase lower Manhattan’s resiliency to storm impact. Rather than come up with one "huge, expensive project," she proposed creating multiple pilot projects that can be built faster and cheaper in order to prove concepts. As an example, Drake said, "we are building a storm water management pilot project in the Gowanus Canal right now."

The final speaker, Albert Appleton, Senior Fellow at The Institute and former Commissioner of the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, talked about the problem of power and climate change in urban contexts. Much of the outer-boroughs and surrounding suburbs are powered by above-ground electrical lines and many of these areas consequently suffered long-term outages after the storm. "Lost power is a problem we know how to solve,” Appleton said. “We have to put our power lines underground. This is not a technically challenging issue, and we can finance it with small, long-term surcharges on electricity.”

The multidisciplinary approach of engineering, architectural, historical, and creative problem solving offered several engaging avenues for thought. Audience members enjoyed the occasionally polemical but heartfelt discussion on a set of problems that have no easy solutions. Adel Assal, father of a Cooper Union mechanical engineering student, found the event timely and necessary, saying: “As citizens we rely on our government for a lot of these protections, but we must also insist the involvement of the academic community from places like Cooper Union to influence policy decisions and forge relationships with government."