COOPERMADE: NYC Sculpture and Monuments

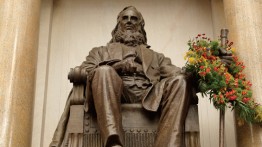

The name Augustus Saint-Gaudens is forever tied to the grandeur of late 19th century New York, where wealthy and powerful patrons frequently turned to the sculptor for the city’s most important commissions. The 1866 graduate from Cooper’s School of Art gained renown for his sculptures of Civil War heroes such as Admiral David Farragut, on view in Madison Square Park and considered one of the finest memorials in the city. Near Central Park’s southeast entrance in Manhattan’s Grand Army Plaza, Saint-Gaudens’ tribute to William Tecumseh Sherman shows the Union general on horseback led by a female figure representing Victory. In the Cooper community, Saint-Gaudens is best known for his sculpture of Peter Cooper framed by a niche and pedestal by Stanford White, the great beaux arts architect. The statue must have had particular meaning for the artist: legend has it that Cooper, who spotted the young Saint-Gaudens sketching in his father’s shoe shop, encouraged the boy to attend his newly founded school, a suggestion that changed the sculptor’s life, as well as the artistic landscape of the city.

While not as famous as his fellow Cooper graduate and eventual collaborator Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Adolph Alexander Weinman A’1891 made his own sculptural impact on the landmarks and monuments of New York City. Weinman, who immigrated from Germany at 14 years old, attended Cooper and eventually landed a job as an assistant in Saint-Gaudens' studio. New Yorkers can see his surviving architectural sculptures around the city: on top of the Manhattan Municipal Building; on the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn; on the bronze doors of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters; in an exterior frieze on the Morgan Library; and in sculptures of Alexander Hamilton and DeWitt Clinton at the Museum of the City of New York.

From 1910–1963, commuters traveling through the original Penn Station daily encountered Weinman’s work: four sets of identical sculptures called Morning Rising and Night Falling—female figures arranged around a clock—as well as 22 eagles set around the two-block–wide building. When the station was demolished, Weinman’s sculptures were either destroyed or became part of disparate collections around the country. One of the clock surrounds can be seen at the Brooklyn Museum, and one of the eagles is currently housed in the roof garden at The Cooper Union’s 41 Cooper Square academic building.