Binding Agents: Student Mentors and EID101

POSTED ON: July 29, 2021

This fall, rising sophomores in the Albert Nerken School of Engineering will step into Cooper’s classrooms and labs together for the very first time, but they won’t be going in as strangers. “EID101 was the first class I made friends in,” says Nada Shetawi, a chemical engineering major who spent the 2020-2021 academic year attending virtually from Egypt. Many, like Nada, are looking forward to finally connecting in-person with classmates they’ve already worked with and gotten to know through their first-semester project course, Engineering Design and Problem Solving (EID101), which was reimagined last year in part to help remote learners find their footing at Cooper.

As a program requirement for all engineering majors, EID101 traditionally provides an immersive, interdisciplinary experience. Amanda Simson, assistant professor of chemical engineering, says it was for that reason the course she was most worried about taking online in the wake of the COVID-19 lockdowns. “It’s very hands-on by nature and is designed to acquaint new students with working in groups and working on projects,” she explains.

She and several other faculty members—professors Martin Lawless, Cynthia Lee, and Neveen Shlayan; adjunct professors Austin Wade Smith and Toby Cumberbatch; and Associate Dean Lisa Shay—set out last summer to reassess the course structure in time for the fall semester. They drew inspiration from the 2020 Olin College Summer Institute, a weeklong virtual workshop dedicated to helping educators design student-centered learning experiences. The faculty team asked not only how they could improve EID101 by incorporating a participatory design curriculum but also how to help the Class of 2024 get to know Cooper—and one another—from afar.

Last week, a few of the faculty members presented what they learned from the process at the 2021 conference of the American Society for Engineering Education. The goal, as Professor Simson puts it, was “to see if this course could be a space for making connections and even friends.” Central to that effort was introducing a new undergraduate teaching assistant model. Each section of EID101, built around various topics under the general theme of “Engineering for Social Good,” was divided up into smaller project teams than in years past, with no more than eight students and an upper-level student TA assigned to each team. “It gives the TAs leadership and teaching experience,” Professor Simson says. “But it also gives the first-year students another point of contact, a contact that's maybe more accessible than faculty.”

Jeannette Circe, a rising mechanical engineering senior, served as a TA in Professor Simson’s class where the projects were all focused on repurposing food waste. “I had one-on-one meetings with students semi-regularly, just to see how they were doing,” says Jeannette. She describes her role as being less of a team leader and more of a resource for students: “It’s about having that person who is not too far removed, a peer who can answer your questions, talk about classes with you, connect you to the campus and to other people.”

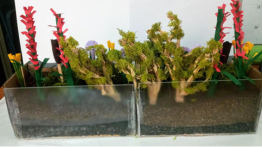

From a first-year perspective, Nada Shetawi says the small groups made for a better bonding experience and that the TAs helped bring students together: “I made friends from my group, and we stayed friends." Their project involved partnering with Cooper’s brewing club and a local brewery to explore methods of converting spent grains into bioplastics and cleaning wastewater using a microbial fuel cell. While some of her New York-based teammates made use of Cooper’s facilities to 3D-print project components, Nada worked from her kitchen in Egypt, building and testing a prototype using PVC tubes. “At first you get frustrated because you don't think you can get something built in three months,” she says. “But finally, after going through the brainstorming, thinking about budget, and getting something that's reasonable to work with from home, it eventually worked itself out. It ended up being so much fun.”

Evan Lutchmidat, a mechanical engineering major, worked on the bioplastics portion of the brewery waste project. He says the group's TA helped keep them organized amidst the difficulties of starting the school year from behind a computer screen: “Working in that group was not only a great experience in terms of understanding how to work with great, strong-minded people, but it helped ease our way into Cooper, so that we would build relationships with people.”

First-year students weren’t the only new arrivals to the course. Cynthia Lee, who joined Cooper as an assistant professor of civil engineering last summer, taught a section of EID101 focused on critical infrastructure and resilience. To help further connect students to the city they would eventually be living in, Professor Lee prompted her class to work on projects that centered specifically on New York. She says the TAs were particularly helpful for facilitating collaboration and sharing knowledge about the wider Cooper community: “I know some of my students were contacting the TAs outside of class about things unrelated to the course, which is great.”

Shirley Yan, for example, worked in Cooper’s Office of Admissions prior to serving as a TA for Professor Lee’s class. “Getting to TA was like a continuation of the things I had been doing with Admissions, where I was actually helping students get comfortable with Cooper,” she says. Mentoring her peers also helped Shirley, a civil engineering major, hone practical skills: “After the fall semester a company that I had applied to for a tutoring job reached out and offered me a position. So, I ended up continuing to teach, and it made online teaching much easier because I had already done it.”

The school of engineering plans on keeping the new course structure and undergraduate teaching assistant model for the coming semester of in-person teaching. Professor Lee explains that “pretty much across the board, students who had TA mentors said in their course survey responses that it was really helpful for getting to know their classmates.”

“When you're working with a group of seven people, there's a lot less opportunity to just vanish into the little black screen,” notes Gila Rosenzweig, also a civil engineering major. “Often those were faces that you would see in other classes as well,” she adds. As part of their project for Professor Lee’s course, Gila’s group designed a rain garden to help mitigate flooding resulting from New York City’s combined sewage overflows. “Our group's TA was really a great sounding board,” she says. “She already had experience with the topic we were researching, so she was there to help us along, but she also let us do as much as we could on our own so that it would really be an experience led by the students.”

Although there were limitations with collaborating online, Gila says she gained valuable design skills: “Were the class in person, we maybe would have had different project ideas. But we were still able to come up with ideas that pushed us to do research, got us involved in the design process, and got us involved in the engineering world.”