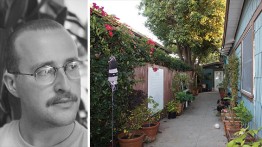

Pulling Up to Art at Troy Kreiner's Driveway 327

POSTED ON: June 24, 2019

Troy Curtis Kreiner may live in Los Angeles but in two critical ways he remains a New Yorker: first, he doesn’t own a car in a city famed for traffic jams and drive-thru cuisine. And second, he knows a few things about making the most of a small space, in this case his driveway which, with no car to park, he has converted into a gallery. Dubbed Driveway 327, the gallery, adjacent to the apartment he rents in Venice, California, has been the site of 15 exhibitions.“Driveways are a valuable resource in LA, so with no car I decided to fill it with art. That inspired the first group show in February 2015, which circulated around this idea of expression in a place of utility.”

Looking for that intersection of function and aesthetics has been central to Mr. Kreiner’s career to date. He started Driveway 327 to share his excitement about artists whose work he admires while developing curatorial themes that engage him, such as handmade textiles as an avenue of queer identity. For his show “Stitch, Woven, Interlocking,” he explored the ways that knitting, weaving, and quilting—traditionally done by women—often provide direct contact with the artist whose ostensible purpose is to make something quite pragmatic—a dishcloth, a blanket, a sweater. As he puts it, “The stitch is an extension of touch, its emotive, it leaves a trail. This friction between function and non-function.”

“Once Solid and Mutable,” an exhibition that opened in November 2018 at Driveway 327, found Mr. Kreiner assembling work from four ceramists (two Angelenos and two New Yorkers) who used the medium to confound material expectations. Sophia Bennett Holmes, an artist from Brooklyn who graduated from The Cooper Union in 2016, made a legal-sized envelope out of clay finished with a creamy white glaze, as well as a miniature ceramic soccer goal, but adding to its surreality, fitted with nets on both sides. Sharif Faragg, a 2018 graduate of USC and resident at Cal State Long Beach’s Center for Contemporary Ceramics, fashioned a hubcap out of stoneware. For the show’s press release, Mr. Kreiner used graphic design to deconstruct a text that characterizes ceramics as merely decorative; using color and simple, hand-drawn lines he supported an excellent text by Griffin Snyder, who argues that the medium has the expressive potential of any other art form, and the ability “to unwrite the terms of its own materiality,” as Mr. Snyder put it.

“Once Solid and Mutable,” an exhibition that opened in November 2018 at Driveway 327, found Mr. Kreiner assembling work from four ceramists (two Angelenos and two New Yorkers) who used the medium to confound material expectations. Sophia Bennett Holmes, an artist from Brooklyn who graduated from The Cooper Union in 2016, made a legal-sized envelope out of clay finished with a creamy white glaze, as well as a miniature ceramic soccer goal, but adding to its surreality, fitted with nets on both sides. Sharif Faragg, a 2018 graduate of USC and resident at Cal State Long Beach’s Center for Contemporary Ceramics, fashioned a hubcap out of stoneware. For the show’s press release, Mr. Kreiner used graphic design to deconstruct a text that characterizes ceramics as merely decorative; using color and simple, hand-drawn lines he supported an excellent text by Griffin Snyder, who argues that the medium has the expressive potential of any other art form, and the ability “to unwrite the terms of its own materiality,” as Mr. Snyder put it.

A native of Long Island, Mr. Kreiner grew up wanting to make art, and while his parents were supportive of that choice they felt that most careers could be successful with or without a college education. That meant that, for the most part, Mr. Kreiner was on his own when it came to financing his schooling. After two years at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, he dropped out of school and went to work as a graphic designer to try raise more funds to continue his education. By then he had moved to Brooklyn. After a year of working, a friend told him about The Cooper Union. “What do you mean it’s free?” he recalls asking.

The idea of getting a full-scholarship education at a top school threw him into overdrive: he found out all he could and then, after a disheartening portfolio review, eventually made an appointment to see Mike Essl, who was then teaching in the School of Art. Mr. Essl, who has since become the dean of the School of Art, recognized the younger man’s talent and realized he’d be a good fit for Cooper.

“After doing two years of traditional Swiss-inspired graphic design education at UArts, I was able to take my design education and completely break it down in a fine arts education,” Mr. Kreiner said. “I was able to situate my own art-making processes, crafting my own curriculum at Cooper, to develop a curatorial practice and express graphic design in unconventional ways. I became independent and found my voice at Cooper Union.”

He took Public Sculpture with humanities professor Michael Dorsch in 2012, who held class at sites around the city. If you scroll through photographs of Driveway 327, you start to understand why Mr. Kreiner credits Professor Dorsch with providing him with a model, or more accurately, models of what sculpture could be and the many ways it could be exhibited.

At point, the group took a tour of Greenwood Cemetery, the resting place of notable 19th century New Yorkers including Peter Cooper. “We visited some incredible mausoleums and at the end of the tour. Jeff [Richman, Greenwood’s historian] briefly showed us a closet of skeleton keys: this was my freak-out moment. I was enamored with this taxonomy of oversized bronze keys, with hammered tags and embossed lettering…There must’ve been at least 400 to 500 keys.” Which doors they opened was long ago forgotten.

Mr. Kreiner offered to scan each set and create a visual archive for the cemetery of all those skeleton keys. The appeal was obvious: keys, after all, can be portable art works that at the same time can be the last word in functionality, given the right lock.

As art director at the graphic design firm Use All Five, Mr. Kreiner has led a number of impressive projects including the creation of the web site version of the Guggenheim Museum’s “Storylines.” The physical exhibition, which ran during Summer 2015, explored how contemporary art is influencing how we tell stories and at the same time is shaped by narratives. Use All Five’s work both documents that exhibition and furthers it by creating an interactive site that lets the user move through the site at random, much as you would through a physical gallery. This exhibition, which continues to live on the Guggenheim web site. They developed the original approach in direct response to the exhibition’s multifaceted nature. “I was trying to think about these different voices, these different styles of art-making, and how that could translate into a typographic treatment,” he says. “So I first started by looking at contemporary type foundries and seeing what kind of work they were making. Ideally, I wanted to put together some kind of combination of different type foundries from different countries, different cities, and find some kind of thread that would unify them—but ultimately [the fonts] all have their own agency, their own unique kind of structure.”

During his senior year at Cooper, Mr. Kreiner, who had been very involved in the movement to keep The Cooper Union tuition-free, was co-founder of NEO, a collective of artists and critics who meet annually to promote free education. It was an initiative that grew out of the conviction that what he found at Cooper should be replicated. His long-term aspiration follows a similar line of thought and comes straight out of the Peter Cooper playbook: “I have a dream for much later in my life to start my own school/program, a small oasis somewhere on the west coast, accessible by train but not in a dense city; a place similar to Cooper Union in ideals but much smaller, merit-based and free tuition. I imagine there will be some certification of sorts with an interdisciplinary focus, no standardized degree.”

He believes that art education needs to be radically reimagined, not least because of the cost of getting an art degree. He’s thought a lot about what he found at Cooper. “I wish many more students get a similar experience. It was a gift, and it shouldn’t be so rare.”