Never Far From Present

POSTED ON: December 10, 2021

For Kenneth Tam, a 2004 School of Art graduate, the most significant stories are the ones that often go unheard. During the early months of the pandemic, for example, the Brooklyn-based artist set out to document and shed light on the disturbing rise in violence and discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans. By March 2020, he began circulating an online spreadsheet asking people to share their experiences of anti-Asian racism, drawing together a wide range of encounters and altercations that might otherwise have gone underreported, particularly amid the sudden isolation of lockdown. The goal, as he describes it, was “to make heard what is often relegated to silence and shame.”

“The spreadsheet quickly took on a life of its own,” Tam says. “It was a very moving and obviously troubling document to read.” The outpouring of responses brought Tam into contact with others working in the art world and inspired them to formulate a collective response, out of which was born StopDiscriminAsian (SDA), a coalition of arts and culture workers committed to mobilizing against racism, xenophobia, and violence towards diasporic Asians. Over the last year and a half, SDA has organized to bring awareness and visibility to these issues, designing posters to hang in Asian communities, hosting online panels and discussions, commissioning artworks, and drafting a widely circulated statement against white supremacy in the arts following the murder of George Floyd.

“I think this intense period of organizing has certainly opened up a space for me to reimagine my own role as a cultural worker, one that is less focused on an individual practice as an artist but more on building community and solidarities across racial and class lines,” Tam says.

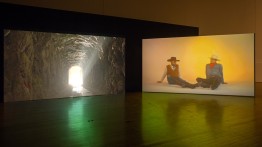

In his recent work, Tam is attuned to the silencing of struggle—particularly where it occurs in the gaps, omissions, and disconnections of dominant narratives. Kenneth Tam: Silent Spikes (2021), his solo exhibition at the Queens Museum this past spring, featured an ongoing series of video and sculptural work that makes use of tropes and conventions specific to the Western. “I wanted to place Asian American men into a space that they have typically been excluded from,” he says. Silent Spikes includes a two-channel video of Asian American men dressed in Western attire, directed to imitate and reinterpret some of the gestures and body language associated with what the artist describes as “the hegemonic masculinity that figures like cowboys represent.”

“The mythos of the cowboy carries significant weight within the popular imagination, and in many ways functions as a shorthand for how this country understands itself and what values it finds most desirable,” observes Tam. “At the same time, the American frontier as depicted in cinema is a very white space, one that largely pushes non-white characters to the periphery, or erases their presence completely.” His use of Asian performers aims at complicating and playing with the cowboy archetype while another segment of video—a slow-moving shot through a rail tunnel—calls forth and narrates the “silent” 19th-century history of Chinese laborers who built America’s railroads.

“Large groups of Chinese migrants worked in mining, agriculture, and of course infrastructure in the West, but you would never know that watching Westerns,” he explains. “I wanted to address both of these issues and see how the struggles in the past can continue into the present.” Silent Spikes makes particular reference to the labor strike led by Chinese Transcontinental Railroad workers in 1867. “So often the history of Asians in America feels fragmented and disconnected, with each successive wave or group of immigration obfuscating the stories of those that came before,” adds Tam. “I wanted to suggest that they actually exist in overlapping ways. History and the past are never far from the present.”

Silent Spikes was also exhibited as a Midnight Moment, curated by Times Square Arts and presented nightly through the month of June across synchronized electronic billboards in Times Square. Next year, the show will travel to Ballroom Marfa, an art center in Marfa, Texas. Tam continues to produce works to augment the exhibition, though the restrictions of the lockdown have made it more difficult for the artist to work in close proximity with others.

“I’m interested in working with groups of individuals to look at how intimacy is created and negotiated, particularly between groups of men,” he says. Movement and embodiment are central to his practice, which spans video, performance, time-based media, installation, photography, and sculpture. “I would say that my interest in working across disciplines was something that began during my time at Cooper, even though it took many more years before I started to stitch things together in a coherent way.”

Tam, who holds an MFA from the University of Southern California, arrived at The Cooper Union by way of the Saturday Program during high school. “All the instructors were current or former Cooper students, and they really impressed upon me how special Cooper was, both as an education and a community. I think the general ethos of the school, which was one that encouraged thinking fluidly across disciplines while maintaining a high level of rigor and criticality throughout, continues to inform my work.” It wasn’t until after graduating that he began experimenting in performance and video, inspired by artists such as Adrian Piper, VALIE EXPORT, and Patty Chang: “I liked the immediacy of using one’s body as a material, and the way it could very quickly address social systems and try to find ways to disrupt them.”

Despite the challenges of the pandemic, Tam says his organizing work with SDA has provided valuable opportunities for reflecting on the relationship between art and social disruption, particularly after the murder of George Floyd in 2020 galvanized large numbers of anti-racist activists across the art world: “This dovetailed with very public calls for accountability at arts institutions across the country,” he explains. Tam sees artists and artistic production as occupying a critical role in agitating for change.

“Artists have tremendous power to start conversations and focus the public’s attention around issues like anti-racism,” he says. “I would urge us all to continue the hard work of organizing for the kinds of changes we want to see in our lives. Very often we sideline activism when things like career demands monopolize our attention, but I think this pandemic has shown that the world we occupy as arts workers is an extremely precarious one, and we really need to think about what systems we want to uphold or participate in.”