Collection of Design Ephemera Highlighting Black Culture Donated to Lubalin Center

POSTED ON: October 31, 2022

In June, poet, photographer, and messenger Kurt Boone donated a collection of magazines, pamphlets, books, and other ephemera of Black culture in and around New York City to the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography. Boone was inspired by a gift made earlier in the year by graphic designer and author Cheryl D. Miller.

Renowned as New York’s fastest messenger, Boone started collecting during the late 1970s, accruing pieces found on his messenger routes as well as by attending hundreds of cultural events over the years. His collection both documents the huge contribution of Black Americans to New York culture of the period and captures the ephemera from the last generation to depend on print for its journals, theater and movie schedules, handbills, and posters. The Kurt Boone Collection at Cooper includes a number of publications no longer in circulation including a copy of BET Network’s now defunct magazine WeekEnd, as well as a magazine called New Words published in Fort Greene in the mid-1990s that captured the vitality of that neighborhood’s young Black artists. That publication, which was put out by a company called BOOM for Black-Owned and Operated Media, included a feature on Donald Byrd and other Black performers and was supported by ads for local businesses, many of which were owned by Black entrepreneurs.

Boone, who grew up in the Cambria Heights neighborhood of Queens, worked for years as a foot messenger in order to pay his bills, build funds for his own business projects, and observe life in New York as material for his poetry. Although he had set out to work in the corporate world, he felt obligated to delay his personal ambitions in order to help young people in his neighborhood who, during the 1980s, were being consumed by the crack epidemic, a period when he observed his beloved middle class neighborhood faltering in the face of the double-barreled threat of drugs and dwindling opportunities for well-paid, secure jobs.

The NAACP tried to intervene in the neighborhood and tapped Boone, who was known in the area because of his success as a track star. “Some of these community organizations asked me to help them quell some of the violence going on and while I was doing it, I was recording everything because some of my advisors in the NAACP asked me to. That’s how I got the taste for building an archive of material.” He stayed in that high-stress environment for several years until, after a stint in the Navy, he decided to move to California to study and refocus on his initial plans to work in business.

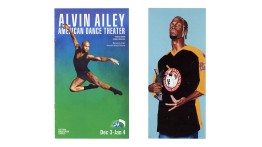

In his memoir, Asphalt Warrior, Boone writes of his repeated attempts to find solid work outside of messengering, but he had no luck finding a white-collar position. Nonetheless, his work as a messenger came to have a huge impact on his business projects, his writing, and his collecting. His legendary status among messengers has made Boone the subject of numerous profiles in newspapers and magazines, including The New York Times. Although these articles focused on his exceptional knowledge of New York’s streets and subway system, what they don’t mention is his passion for documenting the work of Black artists, musicians, and dancers by collecting objects he found while working and regularly attending concerts, art openings, library talks. Among his favorites of the more than a hundred that he donated to the Lubalin Center are a 2015 poster for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater with Glenn Allen Sims soaring against a gradient blue and green background; a card for Raoul Peck’s film about James Baldwin,"I Am Not Your Negro”; a cover from the company G-SHOCK’s magazine with a drawing of a skateboarder seen from the ground level; and a poster from the 2020 show dedicated to Benny Andrew’s portraits at the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

Boone’s enthusiasm, outsized energy, and obvious passion for all forms of art made him equally prolific at collecting ephemera from the world of messengers including Bicycle Film Festival promotional cards and Global Flair: The Style of Cycling Caps, a book by Boone. His standing in the messenger community also led to several businesses—one a messenger apparel and bag company, Rapid Courier 225 Bicycle Company. (225 was Boone’s courier code at one of the messenger services where he worked.)

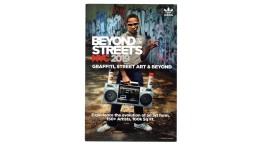

He often used his copious subway time to write and has published volumes of his poetry that often deploys the messenger life as a lens for understanding the city and its people. Boone has also published books of photography that capture the iconography and fashion of messengers, New York City’s subway buskers, and graffiti artists. His latest is a collection of photographs of murals from around the city entitled Fresh Plywood NYC: Artists Rise Up in the Age of Black Lives Matter.

Boone's books are available at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and, in the spirit of the community work he did after high school, he was commissioned by Columbia University's Center for Oral History to interview his family about the effect of the mass incarceration system on the Black family unit. His work can also be found at his website kurtboonebooks.com.

Sasha Tochilovsky, curator at the Lubalin Center, believes the Boone collection captures a moment in New York's Black arts scene just before widespread digitization of such ephemera, making it invaluable as a resource for future scholars. He hopes, above all, that the collection will be used by Cooper students looking to learn about and be inspired by graphic design by and for Black communities.

The collection is open to the public by appointment. To visit, email lubalin@cooper.edu.