Lee Krasner A'29

Mention Lee Krasner (1908–84) and discussion soon turns to her husband and fellow painter, Jackson Pollack, his powerful talent, and the way his career eclipsed Krasner’s. But in another telling, one more in line with an examination of her oeuvre, Krasner found considerable freedom as a lesser-known artist, though one widely recognized within the art world. She was not required by gallerists, museums, or the public to produce more “Krasners”—canvases that bore a recognizable visual imprimatur— but could more freely explore many avenues of painting. “I have never been able to understand the artist whose image never changes,” she once said.

Krasner, a Brooklyn native who was born Lena Krassner, attended Washington Irving High School, known for its art program, and then headed just a few blocks south for college at The Cooper Union. There and at the National Academy of Design, she learned how to portray the human figure as well as still lifes. But after taking classes with Hans Hoffmann and regularly visiting the newly opened Museum of Modern Art, she began to paint using techniques that were less about realistically portraying a scene or a body, so much as creating emotion through form and color. Through the late 1930s to the early ‘40s, she worked for the WPA’s Federal Arts Project assisting on murals, steady work but unsatisfying since these were figurative paintings. During the period right after World War II, she created what’s called her Little Images, about 40 small-scale paintings that read as personal hieroglyphics. By that point, she believed that painting should not focus on a central composition but expand outward, suggesting a life beyond the boundaries of the canvas.

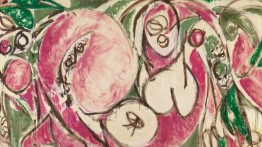

Even as an abstract painter, she approached her work with a deep consideration of the history of painting, from the Old Masters to modernists like Picasso, Matisse, and especially Mondrian. She debated where the medium could and should go next and how her painting could forward that momentum. But such a cerebral approach was later replaced by a more immediate method that became evident in the years after Pollack’s death in a car accident in 1956. Moving from a small bedroom studio at their home in the Hamptons, to the barn where her husband had painted, Krasner began working at a much greater scale and with more saturated color. At the time, friends and critics were shocked by the sudden change in her style, not only because it diverged so much from her earlier painting, but also because some deemed it unfitting a new widow. But a grieving Krasner ignored the criticism and kept working, reporting that she herself was astounded by the paintings and what had been unleashed once she had the space she needed. The result was Earth Green Series (1956-59), which included Sun Woman I (1957), an 8 x 6-foot canvas of rounded shapes, bold, immediate paint strokes of deep pink, brown, green, and curls of yellow. The same year, she painted her best-known work, The Seasons (1957). Called one of the most important American paintings of its era by the New York Times critic John Russell, this painting too explodes with life, its curved lines suggesting fruit and flora. The writer Mary Gabriel likens the 17-foot–wide painting to “a sheet of music” because it works as a kind of document of changing, vast emotion.

The artist’s style continued to change—she explored more somber palette in the early ‘60s, then the bright and floral shapes of the Primary Series later that decade. By the 1970s she used a smaller range of colors and created images that had sharper lines and edges that called attention to the limitations inherent to painting. In 1983, the Museum of Modern Art’s first career retrospective of a woman artist was dedicated to Krasner, though she died before the traveling show arrived in New York City.

Krasner was never one to divorce biography from artistic output. On multiple occasions, she told interviewers that if they wanted to understand her, they should look to her paintings. In 1973, when asked to write a letter giving advice to female artists, Krasner, who disliked being judged by gender, told students that great painting doesn’t capture a fixed image so much reveal a process, a moment in life.

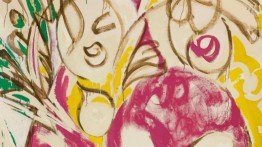

Image Captions, all works by Lee Krasner:

1. Noon (detail), 1947, oil on canvas.

2. Sun Woman I (detail), 1957, oil on canvas

3. The Seasons (detail), 1957, oil on canvas

4. Gaea (detail), 1966, oil on canvas