Thesis Year Snapshots 2016

POSTED ON: May 9, 2016

In the first installment of our annual series focusing on members of the graduating class [see parts two and three], we meet Jemuel Joseph, Max Dowd and Cassandra Engstrom of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. Their thesis proposals, located in Hong Kong, Kigali and in Jemuel's case, anywhere, all examine in their own way the role of architecture in addressing shifting cultural and economic needs. As often happens, a thread appears to run through each, and this year that thread is the profound impact of the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship, awarded each year to a group of fifth-year architecture students so that they may travel to their proposal site or otherwise do research. In each case below, that opportunity had a major impact on the final proposal.

Should buildings be just as culturally adaptable as people? Jemuel Joseph thinks they should. Born and raised in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia until he was 14, Jemuel then moved to Secaucus, New Jersey, so he knows cultural adaptability first-hand. He quickly capitalized on the fresh opportunities his new location brought him: in particular the chance to more fully explore an interest in digital animation and web development. Then in his junior year of high school he attended the Saturday Program at The Cooper Union where, he says, he had his first real experience working in a creative environment. A while later, after a year at Pratt Institute, he transferred to The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture.

Should buildings be just as culturally adaptable as people? Jemuel Joseph thinks they should. Born and raised in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia until he was 14, Jemuel then moved to Secaucus, New Jersey, so he knows cultural adaptability first-hand. He quickly capitalized on the fresh opportunities his new location brought him: in particular the chance to more fully explore an interest in digital animation and web development. Then in his junior year of high school he attended the Saturday Program at The Cooper Union where, he says, he had his first real experience working in a creative environment. A while later, after a year at Pratt Institute, he transferred to The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture.

"I came to Cooper Union because I knew it would challenge my perceptions of how technology is supposed to be used in the field," Jemuel says. "And it has done that every single year. The school of architecture is known for being very critical in the use of technology and very particular about the ways it can be used. That has only reinforced the ways in which I use it myself.”

Jemuel's thesis project, titled "Potentia," the Latin root of "potential," uses technology to explore ways of designing a building that can be adapted to any location and shifting cultural requirements. "It deals with how the accelerating rate of technological change (as in Moore's Law) is affecting the notion of an architectural program, which is something that architects use to build a solution for a certain cultural condition. Because of this faster rate of change, program is becoming more elusive and harder to define. A library built today might not actually be the same library in 10 years. For my thesis I am designing a 14-story tower. It has no program and it has no site."

The building is also virtual and tied to a computer program of Jemuel's own design that allows the input of different conditions. "I am developing it so that you have parameters that can be changed. For example, if the location of the building changes, so do the details of the façade system, so that the shading compensates for the sunlight in that location. The building is intelligent and responsive. The structural system is also deeply tied to the software. So I am using technology in a very specific way. It’s like I’m building this virtual object that has many possible physical manifestations."

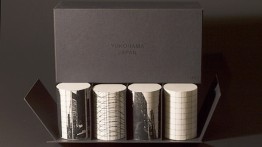

Over the winter Jemuel visited the Cedric Price Archive at the Canadian Center for Architecture, thanks to a grant from the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship. Looking at the work of Price (1934-2003), who was known for insisting on flexibility in architectural design, altered Jemuel's approach. "A lot of the work Cedric Price did was focused on the construction process itself–like the details and parts that make up the building and the economics of the whole system. It wasn't enough to just say, 'This is the building. This is how it looks.' As a result of that trip I also became focused a lot more on the detailing of the building." The final presentation will include models created through Computer Numerically Controlled milling machines, including one that Jemuel built himself with a classmate. "The great thing is that I don't feel tied specifically to engineering or art. I have taken courses in both. They have equally contributed to my interests now," Jemuel says.

After graduation he will work in the tech sector doing things tied to architecture. Further down the line he thinks he may return to Ethiopia. "There's a lot of growth happening in Africa. It's a good time to go there for anyone."

Curiously, Max Dowd also has developed a deep interest for Africa and its potential, though his passion comes as a non-native. Max grew up in Birmingham, England and earned a degree at The Bartlett School of Architecture in London. He spent two years in professional practice, then applied as a third-year "transfer" student to The Cooper Union in order to earn enough credits to receive an architectural master's degree in the U.K. He learned about The Cooper Union from a friend at The Bartlett.

Curiously, Max Dowd also has developed a deep interest for Africa and its potential, though his passion comes as a non-native. Max grew up in Birmingham, England and earned a degree at The Bartlett School of Architecture in London. He spent two years in professional practice, then applied as a third-year "transfer" student to The Cooper Union in order to earn enough credits to receive an architectural master's degree in the U.K. He learned about The Cooper Union from a friend at The Bartlett.

"A vocational master's in the U.K. is very vocational. It's very technical," Max says. "It teaches you how to design buildings in this very direct way. What Cooper has given me is another opportunity to reassess the much larger picture of architecture within the humanities, arts and other different concepts. And that has been completely invaluable to me."

In his late teens Max traveled to east Africa for three months where he developed an affinity for the region. He then returned to Rwanda over the past summer, working for a design group. This, combined with a growing frustration over what he sees as the diminishing role of architects in New York and London into being mere form-givers to pre-determined outcomes, put him in mind of siting his thesis proposal in Kigali, Rwanda. "I became increasingly interested in trying to push the agency that architects can have, meaning processes and not just forms. So my thesis in some ways is a good example of me trying to test that hypothesis."

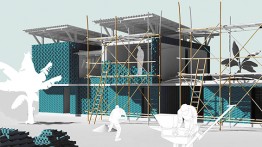

He admits the title is vague: "Constructing Alternatives: Exploring Hybrid Modes of Practice in Kigali, Rwanda." Packed inside that is a master plan that offers an alternative to a complex problem of rapid urbanization in Rwanda and other African countries. Foreign countries are capitalizing on the growth in Kigali, supplying both materials and labor at huge expense, while imposing a form that Max describes as "sparse, suburban topologies" that are "not what the city needs. It needs density." He proposes instead to fashion cities out of low-rise, mud brick buildings in dense patchworks. The materials would be locally sourced, as would the labor, which would then build a skilled middle class that could afford to buy their own homes. But…

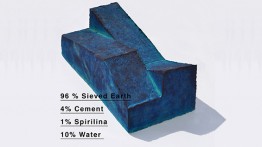

"The problem is these mud brick homes are seen as un-modern and regressive and not in line with the political elite's ambitions for these cities to become global, modern cities. So I set myself the challenge to find a way to formally, structurally and perceptually address earth construction. To try and reframe it in a modern way. So my first semester's work was about getting a really embodied understanding of the materials." He means that literally. He drove around Brooklyn with a van, filled it up with dirt from basement excavations, brought it to the Foundation Building roof and used it to make bricks in his own hand-powered mud brick-making machine. "It was a ridiculous thing to do in the heart of Manhattan," he says.

But without being able to visit his proposal site, much of the master plan was theoretical. That changed with the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship, which paid for a trip to Kigali and Ethiopia for research. "It was a great opportunity to illuminate where I was being naïve and where I was spot-on. And to crystalize some of those ideas that could be seriously assessed as alternatives or even designed in such capacity that they could be built."

The final thesis will be presented as a newspaper in an effort to democratize the information. Max hopes also to put his data online someday. After graduation he will stay in New York for one year until his visa runs out, with hopes of landing at an architecture firm that meshes with his own approach. "I am really desperate to start building," Max says. "Education has been great but it's time for me to build now. So maybe next year I will continue to seek funding for further research and try to test some of these ideas."

Cassandra Engstrom also takes an interest in exploring urban density, but has focused instead on finding ways to examine its surprises and juxtapositions. The interest seems born out of a curiosity for a life contrary to her own upbringing. She grew up in bucolic Ithaca, New York where her father teaches chemical engineering at Cornell. One of his graduate students was a Cooper alumnus and told of its innovative pedagogy, giving Cassandra the idea of applying her interest in the creative arts towards an architectural degree. When she got the famously abstruse home test that asks applicants to supply the likes of a "view with no peripheral vision," she was elated. "The home test was a dream come true. It challenged the parts of my brain that I am most passionate about. I hadn't really encountered that in school at all before. So I devoured it."

Cassandra Engstrom also takes an interest in exploring urban density, but has focused instead on finding ways to examine its surprises and juxtapositions. The interest seems born out of a curiosity for a life contrary to her own upbringing. She grew up in bucolic Ithaca, New York where her father teaches chemical engineering at Cornell. One of his graduate students was a Cooper alumnus and told of its innovative pedagogy, giving Cassandra the idea of applying her interest in the creative arts towards an architectural degree. When she got the famously abstruse home test that asks applicants to supply the likes of a "view with no peripheral vision," she was elated. "The home test was a dream come true. It challenged the parts of my brain that I am most passionate about. I hadn't really encountered that in school at all before. So I devoured it."

Five years later that creative exuberance has been refined and is more "well thought out," Cassandra says. Her thesis, "Charged Proximities" or "Ambient Density" (she can't decide), is sited on Hong Kong Island and was inspired by her interest in the films of Wong Kar Wai, perhaps Hong Kong’s greatest auteur, director of such films as "Happy Together" (1997) and "In the Mood for Love" (2000). "In certain scenes you can see this friction or tension between a private space and a public space," she says. "That's very amplified in Hong Kong because it is so dense and so vertical. There's not a very well thought-out reconciliation between spaces that are in friction. So they are just allowed to be in friction, which I thought was really interesting and a good place for architecture to enter, either to amplify that condition or make it more symbiotic."

After the first semester of online and film research, her thesis had a formal approach that was detached from the reality of the place. But again, the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship allowed her to bring a dose of reality to her ideas with a trip to the actual city. "When I went there I could experience the place through all the senses. Through the smells. What you could hear. Through the lights that were always on. It's a very dynamic city. For every second everything is in constant motion. You also have this collision between very contemporary construction elements like malls that are put right next to these villages. And it's sort of insensitive because there is no grey area to mediate between the two. That experience had an effect on me that I am trying to take into this semester by thinking about the importance of an in-between space that is neutral."

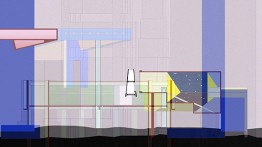

Originally Cassandra wanted to propose a master plan to explore that idea by putting different programmatic elements next to each other. But she needed a framework to organize that chaos. She was inspired to create a mile-long elevated walkway that would cut through the entire city. "I think of it as a spine for the elements I want to balance on it, rather than a reason in and of itself like a park or a green space," she says. "The walkway allows me to organize my ideas along something that stays consistent. So the idea of charged proximity is the idea of putting programs next to each other that are not usually next to each other and seeing what public benefits can happen in that in-between space. For example off this elevated walkway there might be housing that's next to an athletic swimming pool." The walkway would stay at a consistent height and, because of the terrain, start out above ground and end up below ground, inside Victoria Peak.

The proposal will take form primarily in section. "Hong Kong is very vertical. I think the section is an interesting vehicle for playing with density. Because the way things are stacked in section becomes more a driver for innovation than in plan," Cassandra says. The pieces will be long, and viewers will walk along them, as they might on the walkway itself. She also will present models of the walkway, though she says they will be meant more as structural tests of varying methods for support.

Cassandra's plans after graduating remain indefinite, though she imagines she would go to graduate school eventually, but perhaps not in architecture. For now she will stay in New York. About her experience at The Cooper Union she says: "Now I am in a place where I am comfortable enough to take risks that I have to argue for. I was initially afraid of that because I didn't have a strong enough foundation to defend myself, but I just learned to trust myself and follow my instincts as long as they are strengthened by each step I take. The way I tell if a decision is bad or good is by whether it pushes the work further."