Daniel Libeskind's "The Art of Memory" Lecture Excerpts

POSTED ON: May 3, 2013

Daniel Libeskind at the Great Hall, April 2013. photo by Joao Enxuto

World-renowned architect Daniel Libeskind (AR'70) returned to his alma mater to deliver a free, public lecture in the Great Hall on "The Art of Memory." Co-sponsored by The Cooper Union Hillel as a Holocaust Remembrance Event, the designer of the Jewish Museum Berlin, as well as the master planner of the new World Trade Center in downtown Manhattan, among many other major buildings, delivered an entirely extemporaneous lecture about his work to a rapt audience. Some excerpts, with their accompanying illustrations, are below.

The Early Years

I grew up in Poland and my parents were Holocaust survivors. Think about it: the city where I was born, Lodz [originally] had millions of Jews. When I grew up in the 1950s there were no Jews in Poland. None of the members of my family, outside of my parents, [were there.] It was a vacuum. It was something so palpable that it formed my notion of what the world is like what it was like and what it could be like.

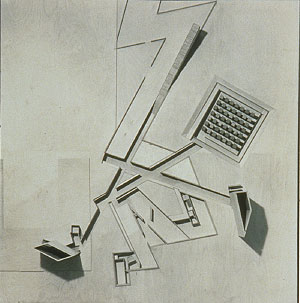

The Jewish Museum Berlin Design

The Jewish Museum Berlin Design

[From above] you see three rows that intersect in seemingly irrational ways but they are actually very well calculated. One row to the right leads to a dead end. There is nothing more to be said about the connection of Berlin to Jews. It's the Holocaust. It's the dead end of the city. It's the dead end of Germany. It's the dead end of humanity. The other row, oblique to it going to a square of 49 pillars, is a Garden of Exile. Not only the exile of Jews from Berlin but exile of the city from itself. And the longest line, the line of hope, is to the main staircase. It doesn't end in a grand space, in luminosity, or come to some conclusion. It ends in a question mark, I think that's important because we have no answers. There are no answers to "why" and "how."

The Holocaust Tower

The Holocaust Tower

Eventually you end up in a place that has no exhibit. No heating in the winter. No cooling in the summer. It is the Holocaust Tower. And when I thought about it, not just as an architect but as a Jew [I asked myself]: is there any light in the Holocaust tower? For the longest time, and this building took many years to construct, I thought, there should be no light. And then by accident I read an account by one of the survivors of Auschwitz. When she was closed in the cattle cars, she looked through a crack and she stuck to that crack. She said it was the only thing that connected to her to the world. And she believed that somehow her survival had to do with hanging on to the light. And I decided to make this cut in this sharp-pointed tower. [This affects] the visitor in a very unexpected way. Right outside this tower there is a school. You can hear the voices of children playing, but you are locked away. [It] does not simulate an event but just gives you a consciousness of what it might mean to be at an end.

Berlin's Future

Berlin's Future

Just recently I was able to complete another project across the street [from the Jewish Museum Berlin.] There was a need for an educational institution. And I inscribed in it, in five different languages words of Maimonides, one of my favorite philosophers, written about a thousand years ago: "Hear the truth, whoever speaks it." That's, I think, the model [for] Berlin, which is a great city, a city that struggles with history, struggles with how to move into the future with that weight of the past that will never diminish, but on the contrary, in my view, will grow.

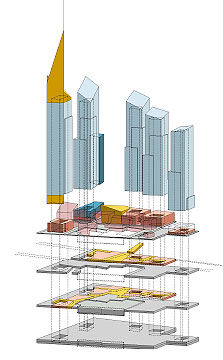

The Master Plan for Rebuilding Ground Zero

The Master Plan for Rebuilding Ground Zero

I did not design two big buildings. I tried to distribute the density across as many buildings as possible in order to make the buildings lower. Not just because they are safer but the streets become better. There is more light. There is more pleasure in walking the streets. I did not want to put the [main] buildings close to Wall Street. (That's where the developers wanted them.) I thought, put them towards the Hudson River. Create a social space at the center framed by museums and by a performing arts center and not just concentrate on grand, private dreams. It's important to remember it is not only a stand-alone site. It is a site connected to TriBeCa, to Wall Street and to Battery Park. It's very critical to take care of how to connect the site not just visually but infrastructurally. It's relatively easy trying to design the buildings that stand on the street. It's what's under those buildings that is the key to the plan. That's the infrastructure: the cores of the buildings, the security, the support system of New York City.

A Flash of Inspiration

I was in One Liberty Plaza during the final round of the competition. It was a rainy, miserable November day. It was depressing. And somebody from the Port Authority said, does anybody want to go into the site? All the architects said, "No it is much better to be here. You can see the site much clearer from up here looking down." But Nina [my wife] and I went down in galoshes with those cheap umbrellas. And my life changed when I descended some 75 feet to this bedrock. I felt the presence of people. [I felt] the presence of death. Also, the presence of where New York comes from. It comes from this bedrock. It was at that moment that I knew what the project should be about. It should be about all the values that we hold self-evident: about freedom, about liberty, about the symbols that need to inform the site.

The Holding Wall

The Holding Wall

So this holding wall, this great dam that holds the waters of the Hudson from penetrating into the entire subway system is a major part of the [9/11 Memorial] museum. I consider it a great accomplishment that all the infrastructure appears below the footprints. [Above them] it's just a space that goes all the way up from the footprints. And you will see the footprints from the bottom, in a museum. It's a special space. It's a sacred space. It's a space that tells you something that no words can tell you. But only by being there next to this raw wall: a wall which is, to my knowledge, the only foundation wall which is alive and has been exposed. Because usually foundation spaces are covered if they are alive. They are exposed if they are dead. In Rome and in Athens you will see foundations of buildings because the buildings are no longer there. But to expose a foundation is a feat of engineering and I was happy to work with the engineers of the Port Authority to make it possible.

The Design of Liberty

The Design of Liberty

I thought that the buildings, even though they stand in a grid, should echo the torch of liberty. And I think they will. [You will get the] sense that the buildings don't throw shadows onto the memorial. They stay on the periphery and create that center of public space. That's very important to me because I was an immigrant to New York, with my sister and my parents. We didn't speak the language. We had dreams that America is something incredible. And coming by the Statue of Liberty early in the morning, in August on a ship, that was something that has stayed with me forever. That sense of the impossible that is possible in America. That New York and America provide not just the rhetoric of liberty but true freedom and liberty. And that's what the site is about.

On Cooper Union

I was very lucky to be a student at Cooper Union. What a privilege it was to be a student here. Nothing could compare to it because it was a school that had ethical principles. Beyond teaching technology and how to put a building together it gave me the freedom to pose the question: why is anything built in the first place? I think that is a question that is underestimated. Most people expect solutions from architecture but questions from everything else. Questions in philosophy. Questions in literature. Questions in art. … But when it comes to architecture it seems to be immune to questions. And yet it is a highly questionable field. [And yet] every building in every city is a question mark. Will it survive? Is it good? Is life worth living in that way? So this school did a lot for me. To inspire me. I was travelling by subway from the Bronx. It took me about an hour with my portfolio and my balsa wood models. Coming here was like a nirvana. I have nothing but accolades for this school.