This Is What Democracy Looked Like: The Photo Gallery

From Monday, October 19 through Saturday, November 7, 2020 the exhibition, This Is What Democracy Looked Like: A Visual History of the Printed Ballot, was installed in the West-facing windows of the Foundation Building. Here we present the text and images in an online gallery. Watch a related panel discussion featuring exhibition curator Alicia Yin Cheng with Samantha Bee and others.

A Visual History of the Printed Ballot

The act of voting has never felt so critical. Accusations of rigged elections, voter fraud, machine malfunctions, and vote tampering put the ballot at the center of the debate. This bureaucratic piece of paper represents our long struggle to make elections free, fair, and honest. Printed ballots embody the material history of our democracy: its ideas, routines, and abuses. These ballots have a story to tell.

Before paper ballots, Americans used things like corn, beans, or their voices to vote. As the population swelled in the early nineteenth century, the adoption of universal manhood suffrage dramatically expanded the electorate. The number of government positions up for election increased too. Political parties proliferated, and each produced its own ballots in an unregulated system. The ballots shown here are eye-catching, colorful, and typographically flamboyant, designed to be easily recognizable by poll watchers and serving as pieces of campaign propaganda. Prominently displayed by voters, they were part of the public spectacle of election day.

By the 1880s, the public demanded reforms to a clearly corrupt voting system. A new format from Australia introduced parameters that seem obvious to us now: an official ballot administered and distributed by the state, a nonpartisan layout that listed all the candidates on one sheet, and the most radical innovation: the ballot was to be marked in private. This new format was not an immediate hit. While it offered equality and privacy, its adoption initiated our enduring history of contested voter intent and disputed mark making—and the end of freewheeling ballot design.

So as we endure long lines, bureaucratic frustrations, faulty machines, and a global pandemic, take a minute to appreciate the mundane-looking ballot you are about to mark in secret. It took over a hundred years for the ballot to look this boring, and that’s progress.

—Alicia Yin Cheng

Presented by the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Established in 1984 the center is an archive of Herb Lubalin's vast collection and the work of other eminent designers from the 20th century and beyond. Herb Lubalin (1918–1981) is best known for his wildly illustrative typography and his groundbreaking work for the magazines Avant Garde, Eros, and Fact.

Installation photos by Marget Long / The Cooper Union

Party Ticket, c. 1870, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

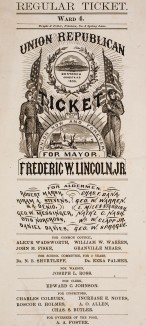

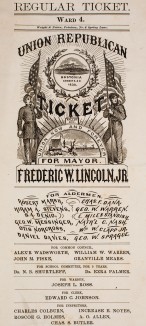

Union Republican Ticket, 1863, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

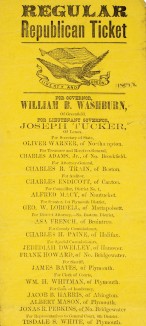

Regular Republican Ticket, 1872, Massachusetts. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

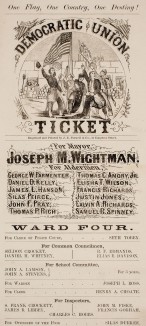

Democratic Union, 1863, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

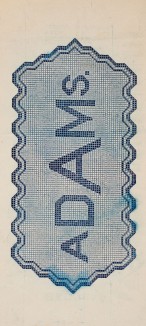

Ballot back, c. 1868, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

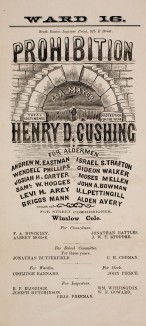

Prohibition Ticket, 1873, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

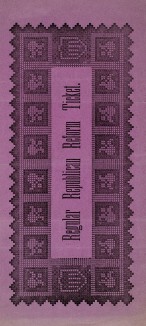

Regular Republican Reform Ticket, back, c. 1870s, Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

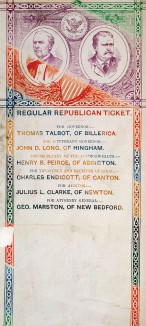

Regular Republican Ticket, 1878, Massachusetts. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

Regular Citizen’s Ticket, 1883, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

Regular Republican Ticket, back, c. 1874, Massachusetts. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

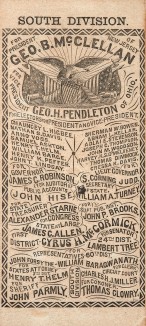

South Division ballot for Democratic presidential electors, 1864. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, California

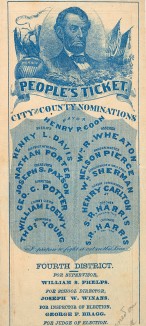

People’s Ticket, 1865, California. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, California

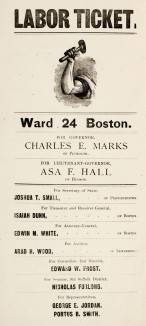

Labor Ticket, c. 1877, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

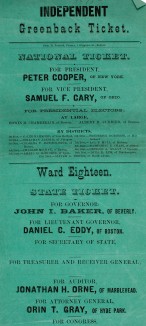

Independent Greenback Ticket, presidential electors, 1878, Massachusetts. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

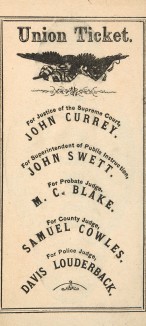

Union Ticket, 1867, California. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, California

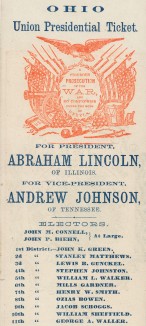

Union Ticket, 1864, Ohio. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, California

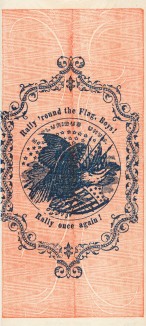

Union Ticket, 1864, Ohio, back. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, California

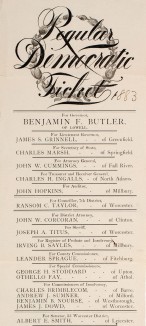

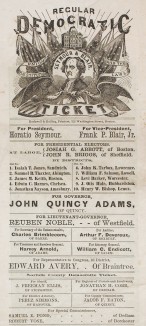

Regular Democratic Ticket, 1883, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

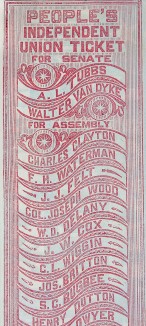

People’s Independent Union Ticket. Courtesy California Historical Society

Union Republican Ticket, 1863, Boston. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

Taxpayers Union Ticket, 1871, California. Courtesy California Historical Society

Regular Democratic Ticket, 1868, Massachusetts. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

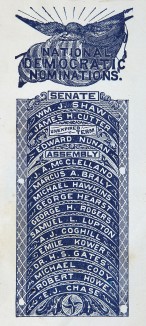

National Democratic Nominations, c. 1880, California. Courtesy California Historical Society

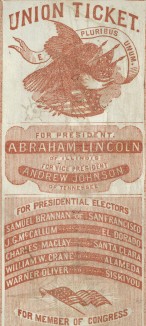

Union Ticket, 1864, California. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, California

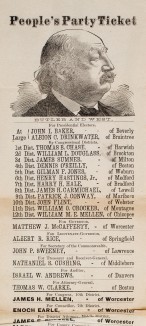

People’s Party Ticket, 1884, Massachusetts. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society

Regular Republican Ticket, 1876, Massachusetts, back. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society