Jean Marcellino (A '60): The Sandra Day O'Connor Project

POSTED ON: December 1, 2008

“Sometimes everything that can go right, does go right,” to quote Neil Leifer, the documentary film-maker. He was referring to the “Sandra Day O’Connor Project,” in which I was privileged to participate.

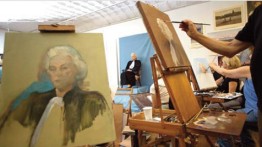

Neil, best known as a sports photographer, had always wanted to make a film about the act of painting. His good friend Walter Bernard, the graphic designer, and he concocted an interesting idea. Walter was a part of “The Painting Group,” an assortment of amateur and professional artists. He suggested inviting a famous person to pose, while Neil recorded the proceedings on film.

Neil and Walter approached another old friend of theirs, David Hume Kennerly, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer, who is a friend of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, recently retired from the Supreme Court. David asked her to come to New York for a one-day sitting. We looked ahead to the big date, October 10th, 2006, both with excitement and a bit of fear. We knew that we had only six hours with our model. And a camera would be intermittently focused on our palettes, our hands, our faces, and most terrifyingly, our work.

On the great day, Justice O’Connor arrived. Our model proved to be utterly winning, charming, and unexpectedly entertaining, even funny. She regaled us with amusing stories from her past.

The director interviewed each of us on camera. The question he asked me was, “What do you hope to accomplish in your portrait?” I answered that my ambition was to do a Gilbert Stuart; that is, a straight, dignified image with my own ego completely absent, and to reflect the Justice’s playful personality while respecting her very great importance.

Jean Marcellino, Portrait of Sandra Day O’Connor,

2006, oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches.

In the end, I rather liked what I had done. Neil and Walter got in touch with the director of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Marc Pachter, who was immediately interested in exhibiting the portraits.

The following spring, to everyone’s amazement, we did indeed have our exhibit at the gallery in Washington, DC., right there in the midst of some of the greatest portraiture our country has produced. All twenty-five artists attended, with Justice O’Connor, of course, giving the keynote speech.

As if that wasn’t enough glory, we then saw Neil’s final cut of the documentary, which was fantastic. The film was sold to HBO and shown on Cinemax. Next chapter: the film was short-listed for the Oscars in the category of “Best Documentary Short Film.” I’ve been told we came in fifth, while only four were officially “up” for the Oscar in that category.

All twenty-five portraits have recently been exhibited at the Millbrook Academy. On a personal note, the most overwhelming thing of all: the National Portrait Gallery has asked to acquire my painting for its permanent collection. It will ship as soon as the Millbrook show ends. I can only conclude by returning to the beginning: sometimes everything that can go right, does go right.