Who Shot Sports: Talking with Curator Gail Buckland

POSTED ON: September 29, 2016

'Narrow Escape—Fire Incident in Hockenheim, German F1 Grand Prix, July 31, 1994' by Arthur Thill/ATP Photo Agency

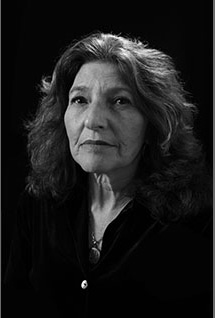

Cooper professor Gail Buckland, the Benjamin Menschel Distinguished Visiting Professor, has curated an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum entitled Who Shot Sports: A Photographic History, 1843-Present. Alfred A. Knopf has published Buckland’s book of the same title. [See at bottom for a lightbox sampling of the work.] The show, which runs from July 15 to January 8, 2017, is an expansive look at sports photography with an emphasis on the aesthetic and cultural importance of these pictures. Both the book and exhibition have received outstanding reviews. Buckland, below, the former curator of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain and the author or collaborator on fourteen books on photography and history, has been teaching the History of Photography at The Cooper Union since the late 1970s. She recently spoke to us about “Who Shot Sports.”

Are you a sports fan?

Not at all.

Why did you choose this subject and how did you make it compelling for you?

I did a very large exhibition and book in 2009, Who Shot Rock and Roll: A Photographic History 1955 to the Present, which went to 10 museums. It was enormously satisfying in that so many people who rarely go to art museums came because of the subject, and when they went they were pleasantly surprised on many levels. Even the most avid rock fans learned a lot because they didn’t know who the photographers were—the photographers of album covers, of the posters on their walls as kids, etc. Who Shot Rock and Roll, the exhibition and book, were very successful. I very much love the history of photography and I love sharing that love with others. My partner was the one who came up with the idea of sports. I said, “How can I do sports —I don’t know about it.” But I do know photography. Sports photography is a form of photojournalism. I realized that I can address many areas of photography through what I know: aesthetics, cultural history, photographic history.

Why do you think sports photographers haven’t been accorded the same respect and recognition as “art” photographers?

Why do you think sports photographers haven’t been accorded the same respect and recognition as “art” photographers?

The photos in the show are made by men and women of enormous talent. Sports photographers have been left out of the canon. In the history of photography, there have always been hierarchies. I have spent my career enlarging the canon. A book and exhibition focusing on the men and women who have given sports its powerful, universal image has never been done. And, when you think about it, sports photography is about capturing the body in motion, and this has been a goal of art since cave painting. In addition, sports photographers, more than any other group of photographers, have pushed camera technology – requiring faster cameras, longer lenses, more sensitive and faster films, cameras that are waterproof, shutters that don’t freeze in extreme cold.

We have a wealth of imagery today, but arguably not presented with the same care and perhaps sincerity of LIFE. Do you think the absence of such photo-driven publications has had an impact on sports photography?

Photojournalism doesn’t exist the way it used to. You still have Sports Illustrated but they have let go all their staff photographers. The difference now is that a great deal of importance is given to speed of transmission and quantity of images shot during a game. There are not many print outlets any longer for sports photography – many people don’t even get a daily newspaper. That’s why a book is important—the photographs have long lives and in a museum show, people have time to reflect on the pictures and look carefully. When they do, they realize the beauty and power of sports imagery.

You included a number of works by people we wouldn’t associate with sports including Andy Warhol and Stanley Kubrick. Why did you make that choice?

Stanley Kubrick was a great photographer before he was a filmmaker, and the picture I used of Rocky Graziano in the shower is a knock out. And it’s a bonus that it was by Kubrick. In terms of Warhol, I tried to be as inclusive as possible because there are different ways of approaching the subject. Those Polaroids [taken by Warhol and included in the book and exhibition] were made for larger art pieces.

You included many of the back stories of how a particular shot was taken. Such narratives are rarely included in exhibitions of paintings or sculptures. Do you agree with that observation, and if so, why would that be the case?

No, I don’t agree. I think it depends on the artist. When the Met does a one-person show on an artist, for instance, a lot of biographical information is available as part of the exhibition. Generally a photograph is taken in real time and under certain circumstances. Beaumont Newhall wrote his history of photography that a documentary photograph must itself be documented because certain types of photographs need good, solid captions. And as a curator, I also try to help the few appreciate the photograph in a variety of ways. For many people these back stories are the best way to enter and enjoy the picture. Then, they can bring their ideas and emotional response to it.

Did your interest in sports increase upon studying these images?

Yes, but what really grew is the recognition of how much sports is loved by people. Sports are loved all over the world and across socioeconomic boundaries I looked for the photographs that helped define people’s passion for sports.

Does your work on the book and the exhibition influence your teaching?

I’ve been teaching a long time and it’s never the same, and I’m certainly not alone at Cooper in saying that the work we do outside of Cooper gives enormous credibility to our teaching. I have renewed energy. I’m not just rehashing things, but conveying my renewed energy and love for the history of photography. I like The Cooper Union students to know their teacher is enlarging the “history of photography” all the time.

Photo of Gail Buckland by James Sprang A'13

Projects

-

Gail Buckland: Who Shot Sports?

Back

Gail Buckland: Who Shot Sports?

-

Arthur Thill. Narrow Escape—Fire Incident in Hockenheim, German F1 Grand Prix, July 31, 1994, printed 2016. Courtesy of the artist/ATP Photo Agency

-

Brian Finke. Untitled (Cheerleading #81), 2001, printed 2003. Courtesy of the artist

-

-

Georges Demeny (French, 1850–1917). Chronophotograph of an exercise on the horizontal bar, 1906. Black-and-white photograph. © INSEP Iconothèque

-

Donald Miralle (American, born 1974). Men's Beach Volleyball Match between Brazil and Canada, London Olympics, The Horse Guards Parade ground, London, 2012. Archival inkjet print 40 x 60 in. Leucadia Photoworks Gallery, courtesy of the artist

-

Brian Finke. Untitled (Cheerleading #81), 2001, printed 2003. Courtesy of the artist

-

Ken Geiger (American, born 1957). Nigerian Relay Team, Olympics, Barcelona, 1992, printed 2016. Inkjet print, 17 7/16 x 19 5/8 in. (44.3 x 49.9 cm). Courtesy of Ken Geiger/The Dallas Morning News

-

Brian Finke. Untitled (Cheerleading #81), 2001, printed 2003. Courtesy of the artist

-

Brian Finke. Untitled (Cheerleading #81), 2001, printed 2003. Courtesy of the artist

-

-

Bob Martin (British, born 1959). Serena, 2004, printed 2016. Inkjet print, 8 1/2 x 12 7/8 in. (21.6 x 32.8 cm) Courtesy Bob Martin

-

Brian Finke. Untitled (Cheerleading #81), 2001, printed 2003. Courtesy of the artist