Azin Valey (AR '90) & Suzan Wines (AR '90): Simple Gestures

POSTED ON: December 1, 2008

A typical wooden pallet measures approximately 48 by 40 inches and weighs between 30 and 40 pounds. Pallets are at once ubiquitous and inconspicuous, both the foundation of the shipping industry and an often jettisoned byproduct in an increasingly global economy. But discarded pallets can also be seen in other ways—indeed, in the eyes of architects Azin Valy (AR’90) and Suzan Wines (AR’90), pallets are inexpensive, versatile and sustainable building blocks that can be used to create transitional housing for people displaced by natural disasters and humanitarian crises, as well as to provide permanent affordable housing for the growing number of people living in substandard conditions all over the world. Valy and Wines are the principals of I-Beam Design, a young firm based in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. Along with the various adaptations of the pallet-house concept—as refugee housing in Kosovo and disaster-relief housing in Sri Lanka for instance—I-Beam has developed a portfolio of contextual, flexible and playful schemes for urban spaces, façades and interiors since its founding in the late 1990s. From a hanging garden over a park in New York City to a mixed-use condominium development in Manchester, England, every project shares a common thread—in each, a simple gesture serves multiple functions.

Valy and Wines are the principals of I-Beam Design, a young firm based in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. Along with the various adaptations of the pallet-house concept—as refugee housing in Kosovo and disaster-relief housing in Sri Lanka for instance—I-Beam has developed a portfolio of contextual, flexible and playful schemes for urban spaces, façades and interiors since its founding in the late 1990s. From a hanging garden over a park in New York City to a mixed-use condominium development in Manchester, England, every project shares a common thread—in each, a simple gesture serves multiple functions.

Long before founding I-Beam in 1998, and prior to meeting in a second-year studio at Cooper Union in the late 1980s, Valy and Wines developed their early interests in design half a world away from each other. Valy was born and raised in Iran. As a child she was an avid drawer and knew she wanted to be involved in design in some way—she just had a little trouble narrowing her focus. “My father would say to me, ‘What do you want to do when you grow up?’” says Valy. “And I would respond, ‘What do you call that profession where you can design doorknobs, toys, clothes, houses, landscapes, cars and airplanes?’ He’d tell me that I couldn’t do them all, but that I could study fashion design, interior design, architecture or industrial design, and I’d say, ‘Well, if God can do it, then I want to be God!’”

When Valy was nine, her father built his dream house in Tehran. “That was a fun period for me because I could immediately relate to plans, sections and drawings and I was allowed to participate in the planning of the house,” she says. “My mother went away to Europe to buy the appliances and tiles, and during that time each family member was assigned a certain chore around the house. I was responsible for keeping things tidy. For a month, I kept things very tidy. I loved it, and thought, ‘I want to be maid.’ So, in the end, the happy compromise was to be an architect—between God and being a maid I chose architecture.” Meanwhile, over 6,000 miles away in New York City, Wines spent much of her youth

Meanwhile, over 6,000 miles away in New York City, Wines spent much of her youth

perched on the edge of the drafting table of her father, the sculptor and architect James Wines. In 1970, James Wines and a few artist friends founded SITE (Sculpture in the Environment) in the family’s Greene Street loft. Approaching architecture in the urban environment from a conceptual art point of view, SITE became well known for the peeling, deteriorating and distorted brick façades of nine BEST Products Company catalog showrooms. In a scheme called the High rise of Homes, SITE proposed stacking 15 to 20 vernacular, mixed-used communities on top of one another in a steel and concrete structure in an urban environment.

“It was a huge influence,” says Wines, “I basically grew up in an architecture office asking,

‘What are you doing? Can I make one too?’ There was a real sense of community and a philosophical discourse going on—not that I participated in the philosophical discourse, but I understood that something very exciting was happening. It was all about fun and change and new ideas. I imagined that when I grew up, I and a group of artsy types would sit around and re-invent the world as well.”

Wines chose Cooper Union after attending a high school for music and art in Harlem; Valy transferred to Cooper after initially studying at Virginia Polytechnic Institute. Both note the influence of professor Raymond Abraham and Dean John Hejduk, as well as the demanding academic environment that Cooper provided.

“There was a level of expectation of cracking the barriers,” says Wines. “Not only did you have to come up with a completely original idea in your projects, but then you also had to find the perfect way to present it. You could take any conceptual idea—whether you had a particular interest in dentistry, economics or the stock market—and apply it to your discipline of architecture. You could take all kinds of ideas from literature, poetry, philosophy, music, any of the applied sciences, and reinterpret them through the discipline of architecture.”

After graduating in 1990, Valy worked briefly at Gensler and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, went back to Iran for a couple of years, and returned to New York City to work at a few small firms. Wines worked at a few small firms and spent three years with Kohn Pederson Fox Associates. One day they ran into each other and decided to enter a concept competition sponsored by Storefront for Art and Architecture to redesign Lt. Petrosino Park, a 7,000-square-foot triangular space at the intersection of SoHo, Chinatown and Little Italy in New York City.

“The existing park is isolated and has no life—it’s a hole in the middle of a potentially vibrant neighborhood,” says Wines. “The public and private spaces are separated by lanes of traffic, so we had the spatial question to overcome, as well as the division between the three neighborhoods.” Valy and Wines’ proposal—which would be the winning design—was a garden canopy growing up columns in the park that would extend over the lanes of traffic to the neighboring buildings via a gridded matrix of cables. Residents in the neighboring buildings would be given planter boxes and could grow plants and ivy that would extend into the park. The conceptual and physical connection between public and private realms would break the spatial limits of the park; the canopy would reduce noise and air pollution to the neighboring buildings; and, as Valy notes, “The cables could be used by artists as a structural support for artwork, and each community could use the cables to hang things for their unique celebrations—Chinese New Year, Christmas and the San Gennaro Festival.” In 2001, I-Beam designed the renovation of a 3,000-square-foot loft in NoHo. In the kitchen, the bottom section of a stairway leading to the roof deck is actually a cabinet that

In 2001, I-Beam designed the renovation of a 3,000-square-foot loft in NoHo. In the kitchen, the bottom section of a stairway leading to the roof deck is actually a cabinet that

can be moved and used to, say, replace a light bulb—so the unit functions as a stairway, step ladder, kitchen counter and cabinet. In another playful touch, an aquarium made of liquid-crystal glass separates the entry vestibule and the master bedroom. When switched on, the glass becomes clear, allowing a view of the bedroom and flooding the entry with light; when switched off, the glass becomes opaque, creating privacy.

In another loft renovation, the clients wanted to create a gallery for their collection of contemporary abstract paintings by South American and Cuban artists. I-Beam collaborated with Cooper professor and artist Joan Waltemath, who, by using a matrix of numerical ratios, creates paintings that resonate with architectonic space. “Ms. Waltemath created a unique work of art at the origin point of the matrix that is at once a painting, a sculpture, a hearth, a door and a source of light and animation within the apartment,” says Wines.

“This multifunctional approach is typical of our work as well and became a means by which we negotiated between Joan’s two-dimensional rendering of space and our three dimensional vision. “The idea was to project her matrix into three dimensions to generate the various programmatic elements of the space.” To display as many paintings as possible, sliding panels allow two or three levels of paintings to be shown at different times; when a sofa is opened into a bed for guests, a panel pivots out and creates privacy, and another painting is revealed behind it.

In 2003, I-Beam entered a competition to design a housing condominium along the River Irwell in Manchester, England. When they visited the site, Valy and Wines were struck by a few things: the canals in the area; the barges that traveled along the canals and in some cases provided affordable housing; the stepped landforms with stone retaining walls; and, although it was November, the greenery of the surrounding landscape. Taking all of those things into consideration, Valy and Wines decided to create a scheme with two mixed-use buildings integrated into the landscape with grass eco-roofs in a stepped setting of communal and private lawns. A canal would also be cut behind the development and canal-side apartment dwellers would have barges attached to their homes that could be used as guest apartments, studio spaces or greenhouses—and also “unplugged” and used for transportation. I-Beam’s scheme also called for the city to utilize the barges like city buses.

“That way we would encourage the use of the canals in the city—they were about to start cleaning them up and making use of them at the time,” says Valy. “It would encourage farmers to come from other parts of the country and other parts of the city to create a farmer’s market—so it would bring economy to the site. A big open space at the center of the development would function as a pool in the summertime, an ice-skating rink in the winter, and at other times could be used as an outdoor amphitheater.”

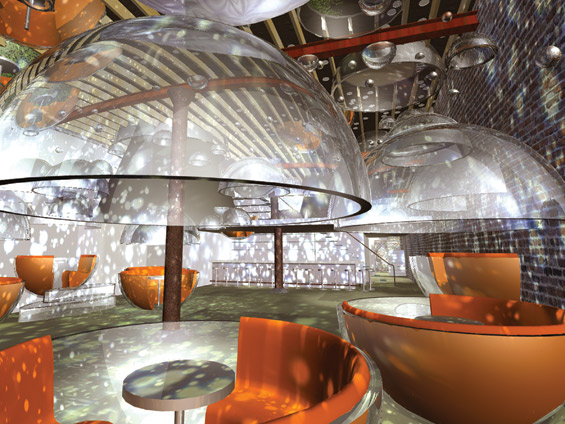

Other recent schemes include a wine bar in SoHo with two floors connected by a waterfall

that flows through the bar; a galactic-themed nightclub in Chelsea with seating pods below hoods that can be raised and lowered for varying levels of privacy; and a condominium building on 23rd Street with mirrors integrated into the curtain wall to bring light into the interior.

“Privacy pods:” The design for a galactic-themed nightclub in Chelsea includes hoods that can be adjusted for privacy—so an occupant could hold a conversation in the middle of the dance floor.

Although some of the schemes in their portfolio have not been realized, Valy and Wines are optimistic they will be built—in the case of the pallet-house designs, built at a large scale in humanitarian crises. The concept was initially a submission for Architecture for Humanity’s Transitional Housing competition for Kosovar refugees in 1999. “We wanted to take something that is often discarded and potentially recyclable and make a house out of it,” says Wines. “We had a bunch of ideas, but one night we decided that if we didn’t come up with an idea that we really liked by the morning, we wouldn’t enter the competition," says Wines. “I decided to walk back home to Brooklyn and see if anything occurred to me, and I walked out the door, tripped over a pallet and said, ‘Ah ha!”

I-Beam’s scheme received honorable mention in the Transitional Housing competition. Versions of the pallet house have been built in the South Bronx, at Ball State University and, more recently, a full-scale house was built for the Casa per Tutti Exhibition at the Architecture Triennale in Milan, Italy. An adaptation has also been developed for tsunami victims in Sri Lanka. “The idea is that it would transition from a temporary shelter that you could put together really easily into a permanent house,” says Wines. “Pallets seem to offer the perfect solution. You could get fifty pallets and strap them or nail them together, put a tarp over the structure for a few months, and then by the time the tarp breaks, you can collect local mud, rubble, plaster, cement—whatever might be available—and fill in the cavities, clad the house and make it a more permanent structure. Plus the pallets would simply be arriving in vast numbers with all kinds of aid in a refugee situation—the shipments of clothing, food, medicine and building supplies would all be coming on pallets anyway.”