Cooper Union Builds Brave New World: The Poetics of Sustainability

POSTED ON: June 1, 2007

There is no doubt that global warming has finally become a focus for people around the world. Now the subject of intense scientific and public scrutiny, the subject demands solutions both intellectual and practical—and swift. In February of this year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was put together by the United Nations, reported that carbon emissions are at an all time high and that “warming of the climate system is unequivocal.” Since new construction accounts for almost 50 percent of production of greenhouse gas emissions, it’s no wonder that architects are incorporating green ideas into their practice. Many graduates of The Cooper Union’s Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture are taking a leading role in responding to the global environmental crisis by integrating issues of sustainability into their designs and, for those who have leadership positions in academic institutions, into their curricula.

Some people have been aware that the planet’s environment has needed protection for the last 30 or 40 years. As Toshiko Mori (AR’76) says, “The big question is ‘why now?’” Mori, who is the chair of the architecture department at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, as well as the principal in her own practice in downtown New York City, explains that this is something she’s always integrated into her designs and into her curricula. She co-teaches an engineering class for her students with Matthias Schuler, a German climate engineer. Her students, as she says, “are aware of the cultural, political and scientific issues that come up in our daily lives” and they use those in conjunction with research on various elements of climate change, including carbon emissions, water management and alternative resources, in order to bring their work to the forefront of designing buildings that are environmentally responsible. The question “why now?” is a good one. Stan Allen (AR’81), dean and professor of architecture at Princeton University, hypothesizes that it’s got everything to do with urbanization. “Architecture,” he explains, “has been and will be associated with urbanization and modernization.” Many of the social and environmental issues that architects will face in the near future stem from the problems created by the tumult of recent urban expansion. “Cities like Lagos, Jakarta—and already cities like Mumbai or São Paolo—are expanding much faster than Paris, New York, Tokyo or London. There is an incredibly rapid expansion in developing countries and, in many cases, the infrastructure can’t handle this rapid development, and we’re seeing environmental, social and political consequences.”

The question “why now?” is a good one. Stan Allen (AR’81), dean and professor of architecture at Princeton University, hypothesizes that it’s got everything to do with urbanization. “Architecture,” he explains, “has been and will be associated with urbanization and modernization.” Many of the social and environmental issues that architects will face in the near future stem from the problems created by the tumult of recent urban expansion. “Cities like Lagos, Jakarta—and already cities like Mumbai or São Paolo—are expanding much faster than Paris, New York, Tokyo or London. There is an incredibly rapid expansion in developing countries and, in many cases, the infrastructure can’t handle this rapid development, and we’re seeing environmental, social and political consequences.”

Because a lot of new building is going on in developing areas, the question of sustaining local cultures also comes up as an issue. Allen thinks that indigenous cultures, like other cultures, change over time, and that many have clearly shown that they want to modernize and have access to the conveniences that modernization brings. He feels strongly about allowing cultures to evolve rather than imposing our views on them: “That’s paternalism: we’re telling them what we think their culture should be.” In fact, he feels that globalization—or the combination of local cultures plus the effect of modernization and Westernization—will lead to “cosmopolitanism,” a term associated with Kwame Anthony Appiah, a professor of philosophy at Princeton. Cosmopolitanism simply says that the hybrids created by globalization will be more interesting than preserving local cultures, since they create a dialogue between the world’s peoples rather than relegating them to a pristine and unchanging past. Evan Douglis (AR’83), who is the chair of the department of undergraduate architecture at Pratt, agrees, and sees this as a challenge for architects of developing nations. China, for example, is interested both in being a part of the contemporary design community and sustaining its unique cultural history. The danger of globalization, as he sees it, “is that speed without content is meaningless, or more importantly, is fundamentally subversive, because it will take a heterogeneous system, which is comprised of all these beautiful cultures that have long lineages of uniqueness, and homogenize it.”

Where architecture once reflected unique mythologies and ways of life, it now runs the risk of universally reflecting a minimalist, industrial aesthetic. “Sustainability,” Douglis continues, “should be linked to the poetics of local culture, which in turn, is linked to the well-being of the planet.” He foresees architecture that is not just localized, but individualized in terms of the poetics that sustainability will offer. Often, sustaining local cultures is tied in with the aesthetics of green buildings. Peggy Deamer (AR’77) sees this happening first hand at her new post in New Zealand. She recently moved there to become the head of the University of Auckland’s National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries’ School of Architecture and Planning. Formerly the assistant dean at Yale’s School of Architecture, Deamer was impressed by the difference in building green between the United States and in New Zealand. “There is much more of a consciousness about it at a public level here. I’ve seen billboards that talk about your ‘carbon diet’!” she says. But, more than that, architecture in New Zealand offers an idea of what the hybrids of globalization might look like. The Maori, New Zealand’s indigenous population, are quite involved in the development of their country: Deamer explains, “You don’t ever propose something that doesn’t take into consideration all of the cultural rituals and paradigms that are socially meaningful to the Maori. Some of the leading architects here are bending metal and patterning things in a way that goes hand in hand with an aesthetic that comes from Maori culture.” This is especially evident in what she calls the “tattooing of the surface of the building,” which echoes Maori cultural practices. Like Allen and Douglis, she believes that the issue is having modernism and local cultures co-exist, so that it’s not just imported and imposed Westernism. So what is the role of the architect in all this? How do you make thinking green not just a priority, but a taken for granted reality? Allen suggests that it’s not just about new technologies or techniques that make for a smaller footprint; it’s really about changing the mindset or approach to architecture. “Even five or six years ago, questions of environmental responsibility or sustainability were something added on. Today, it has to be automatic: it’s no longer optional. Just as we wouldn’t train our students to build a building that would fall down, we wouldn’t train them to design buildings that use resources irresponsibly. It’s incorporated integrally into our curriculum. We have what we call an integrated building studio where we bring in environmental engineers, sustainability experts. It’s much less about the bells and whistles than about simple decisions about the orientation when you site a building and how it’s going to relate to the sun angles.” Deamer feels that New Zealand offers a place-based studio for architecture students because of the wide climatic variation, running the gamut from sub-tropical to temperate to extremely cold. The country attracts a wide variety of students who can use this outdoor laboratory and then bring the results back to their own countries. Deamer puts it like this: “They’re speaking about global issues here, and there are students from all over the world whose interests are in their native countries, so the cross-fertilization that happens here in terms of ideas is amazing.”

This is especially evident in what she calls the “tattooing of the surface of the building,” which echoes Maori cultural practices. Like Allen and Douglis, she believes that the issue is having modernism and local cultures co-exist, so that it’s not just imported and imposed Westernism. So what is the role of the architect in all this? How do you make thinking green not just a priority, but a taken for granted reality? Allen suggests that it’s not just about new technologies or techniques that make for a smaller footprint; it’s really about changing the mindset or approach to architecture. “Even five or six years ago, questions of environmental responsibility or sustainability were something added on. Today, it has to be automatic: it’s no longer optional. Just as we wouldn’t train our students to build a building that would fall down, we wouldn’t train them to design buildings that use resources irresponsibly. It’s incorporated integrally into our curriculum. We have what we call an integrated building studio where we bring in environmental engineers, sustainability experts. It’s much less about the bells and whistles than about simple decisions about the orientation when you site a building and how it’s going to relate to the sun angles.” Deamer feels that New Zealand offers a place-based studio for architecture students because of the wide climatic variation, running the gamut from sub-tropical to temperate to extremely cold. The country attracts a wide variety of students who can use this outdoor laboratory and then bring the results back to their own countries. Deamer puts it like this: “They’re speaking about global issues here, and there are students from all over the world whose interests are in their native countries, so the cross-fertilization that happens here in terms of ideas is amazing.”

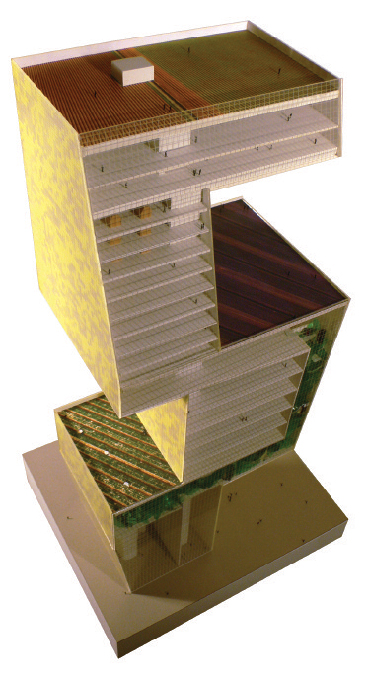

There are several ways to approach this new outlook on sustainability. Allen asks, “What kind of new city are we imagining?” Ironically, he says, older city models were more environmentally conscious—the smaller scale that allowed for walking rather than driving, or buildings that used natural ventilation provided by opening and closing windows. So Allen suggests that architects incorporate some of these elements of older urban planning: for example, by avoiding urban sprawl, cities can be created that don’t need cars. He believes that the institution of the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standard by the United States Green Building Council was an important step. Deamer proposes another tried and true method: focus on the local. She wants us to think about the indirect resources that we consume: “You shouldn’t just be thinking about not using materials that are limited in supply, but about the very way in which we measure carbon consumption. How far have you asked your laborers to drive? How far do the resources have to travel? Did they come in a truck? In a boat?” Another billboard she’s spotted in Auckland is a good example of drawing attention to the indirect. It instructs “Travel more economically: Blow up your tires.” Douglis thinks about a future where we’ll start looking more to nature and natural processes in revising the way we build. “Why isn’t it possible to find a more harmonious integration of the distribution of the energy that is constantly drifting around the planet? The answer is, it can be. There are a number of disciplines that have been looking at nature in order to understand the logic and the underlying structure that is responsible for unusual and spectacular affects.” The question he poses is “can architecture adapt these processes, maybe replicate something like the absorption and distribution of energy as in photosynthesis?” Mori’s philosophy is similar: while she believes that the role of the architect is to “minimize or make a zero carbon footprint,” she wants to take it a step further. Better still, why not make buildings that “generate their own energy using renewable resources”?

Douglis thinks about a future where we’ll start looking more to nature and natural processes in revising the way we build. “Why isn’t it possible to find a more harmonious integration of the distribution of the energy that is constantly drifting around the planet? The answer is, it can be. There are a number of disciplines that have been looking at nature in order to understand the logic and the underlying structure that is responsible for unusual and spectacular affects.” The question he poses is “can architecture adapt these processes, maybe replicate something like the absorption and distribution of energy as in photosynthesis?” Mori’s philosophy is similar: while she believes that the role of the architect is to “minimize or make a zero carbon footprint,” she wants to take it a step further. Better still, why not make buildings that “generate their own energy using renewable resources”?

“The beauty of the time we live in,” Douglis says, “is that we, as architects, can cross out of our own discipline and collaborate with a whole series of other disciplines.” In fact this is absolutely necessary in order to make a clean, green planet a possibility. As Mori points out, “this is a global issue. Architects need to engage in a collaborative dialogue with scientists, with the business community and with political leaders.” As awareness grows of the problems we’ve caused to our environment, everybody is going to have to do their share to help fix them. By envisioning sustainability not just as a surface remedy but as a new consciousness that will enable us to care for our planet more deeply, architect educators like Allen, Deamer, Douglis and Mori ensure that our children and grandchildren, and hopefully many generations beyond, will have a place to call home.