Prof. Diane Lewis Celebrates Her Newest Book and 40th Reunion

POSTED ON: June 1, 2016

Models from the Design IV: Architecture in the City studio on display in the west colonnade. Photo by João Enxuto

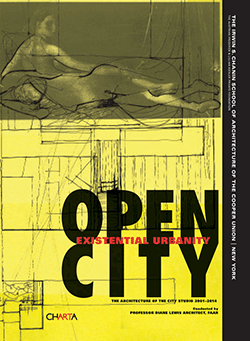

Last November Diane Lewis AR'76, a professor of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture who has taught at the school for over 30 years, saw a major benchmark in her already storied career with the publication of her book Open City: Existential Urbanity (2015 Charta, Milan). Created with a team consisting of instructor Daniel Meridor, AR’06, M.ArchII’10, as well as Matthew Hitscherich AR’12, its official release was marked with a book signing at The New Museum on Nov. 19, followed by a symposium at the Museum of Modern Art and the New Museum on November 20 and 21, respectively. The book -- a large-scale, luxuriously illustrated tome -- showcases the student work that emerged out of the fourth-year "Architecture of the City," studio from 2001 to 2014 led by Professor Lewis. Each chapter of Open City focuses on the thematic exploration in a given year, including an essay by one of the studio professors, a final exhibition installation photograph, the project brief that was given to the students, and examples of their responses to it, including drawings, models and texts. For the two days of panels, 55 alumni returned to New York from their current practices and teaching posts all over the world. Twelve members of the Cooper faculty and Dean Tehrani, as well as 30 international guest architects, spoke to celebrate the book. On June 4 Prof. Lewis will be leading a tour for Reunion 2016 (including her own 40th year reunion). We sat down with her to talk about the book, her approach to architectural pedagogy and the tour.

Why is the book titled Open City?

Why is the book titled Open City?

It’s named after the 1945 Roberto Rossellini film, Roma, Città Aperta ["Rome: Open City."] Neo-realist cinema was an obsession from my childhood. Those directors sited their movies in relationship to mythic or historical things that occurred there. Or they would also be able to cast a particular spatial arrangement as being that of a piece of literature, for example, in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Oedipus Rex” (1967). So that ability, that poetic ability, is an articulation of the ancient responsibility of an architect. The ancestor of Roberto Rosselini was the very Renaissance architect Rossellino Rossellini, who resurrected this idea of the site as an existential marking of the actual event that took place there! Thus the neo-realist cinema is a resurrection of this architectural concept! Like an auteur director, an auteur architect has to ask critical questions: What subject matter? What shots? What montage? What order, spatial sequence, ceremonial passage? What’s the program? What’s the form? Is there relation between form and program? What do you believe in? What do you want to espouse?

The fourth year studio pedagogy underscores the importance of establishing the role of buildings that are no longer extant, with people no longer physically present. Why is that awareness of past forms and programs critical for an architect?

In the case of the projects featured in Open City, I’m interested in establishing that the participants in the studio see first that any site has transformed. A lot of the time bad architecture professors give students empty lots to develop a commercially-based thing. The seminar that I teach, which is a structural appendage to these studios, is about singular buildings that address the entire form of the city. With it you study the transition between Renaissance Rome, Sixtus V Plan, and how that plan went through Bernini to Paris, how it evolved after the French Revolution, how the Haussmanian version of it is a kind of military industrial complex with air blown into it, and how those kinds of visions of civic space and humanitarian program evolved from being monarchical and ecclesiastical—as Victor Hugo said, from theocracy to democracy. All of a sudden after the Revolution, you had to think of clinics, post offices, schools, orphanages, libraries: so the whole aspect of the site morphology in this case is to really look at the evolution of the civic programs and how in fact a site can have memory.

In Open City, you described the studios as exploring “architectural urbanistic work” as opposed to urbanism or urban design. What's the difference?

In Open City, you described the studios as exploring “architectural urbanistic work” as opposed to urbanism or urban design. What's the difference?

The churches in Rome were sited where the martyrs were martyred. In America, we don’t do that. Where would you put a church? Isn’t it the role of the architect as opposed to just the builder/geometer be called upon to say where things should be? Frederick Law Olmstead's vision for Central Park is an unbelievable accomplishment. New York is a post-Jeffersonian, post-revolution-of-the-individual, democratic, capitalist city that has a park the size of a royal park in England or Germany! Huge concepts and devices had to be invented in a democratic society because of the vision of an architect who saw a void and what to do with it. If Olmsted had restrained himself to what was possible in the conditions of the society, we would never have Central Park.

Among the studio's “concerns and roots” you include both visual art and a seminal text by Freud. How do fields such as psychoanalysis and painting inform an architecture student?

The most exciting work of the architect is to understand the city as a work of art. To work on the civic space enlivened by the art of tectonic space and the integration of all different epochs of structures and buildings together into a “still life,” with the artist, the works of art; the sculpture, the painting and of course contemporary art integrated into that civic space and must be a part of the marking of the existential facts of that place. Artists and architects can inspire ideas back and forth. It’s the idea of advocating great civic space as the work of artists, architects and engineers together, which I believe is the original motive of this school.

Once you ask any of the Cooper Union students, ”What humanitarian, emancipatory program would you want to design,” they get more excited about being an architect because instead of thinking there’s going to be a brief or requirement that comes to the architect, they understand that they will, at some point in their lives, determine what architecture they want to create and where they will position their work in the city as a citizen and a person who is an architect/master builder. This aptitude for siting the work in a significant position in the urban fabric, on the planet, in man-made or natural architecture, is the signifying aspect of the architectural mind. And both the neo realist directors and the modern movement architects strove to return this power to the architect. Critical practice as upheld and defined by my teaching and that of my major colleagues at Cooper is sustained by this ability, the art of the city as architecture, and knowledge of how to read a site.

Tell me about the design of the book.

This book is the exact same size as the Atlas of Urban History by Mario Morini, which is a book that shows the history of civilization in plan. Its table of contents shows each city as it was from prehistory through the ancient , medieval, renaissance to the 1960s. It’s a testimony to the power of architectural notation being immortal – it proves that one is able to project new readings from the same text over time—and that whatever you think of now could live on for centuries and could be realized after you, even if poetically misread and restructured, as an inspiration to civic space. Having purchased this immense volume as my graduation gift to myself in 1976, and carried it with me as my guide to the underlayers of civilization wherever I traveled, I wanted these students to be launched in the world with the same level of refinement and layout of this publication on their ideas of the city as a work of art and civility, as I had when referring to the magical Morini book.

How does it feel to have the book finally published?

I’m so glad that I’ve been able to bring this to the school at a time when we have a new dean and he can be recipient of this connective tissue in terms of the refinement of architectural thought here. I don’t believe it’s about history or the past, and I don’t believe it’s about the future. I believe it’s about the existential character of a really hip architect to examine and observe the potentials of any space of and within the city and to generate interest among artists to work with them, integrate people from the artists community—concepts texts and works. That’s what I think it takes to make a city of great civilizing force. And I believe that New York is one of them and the place to do this, and there’s an intrinsic role for the Cooper Union thinkers as described in the founding principles. William Cullen Bryant and Peter Cooper were a team to root our architects and artists in the art of creating New York; not just in terms of beauty and design but in terms of which civic institutions support a refined and humane life and where they are positioned and how their form speaks the vision of their authors. I try to teach this.

This year you will be giving a tour for alumni during Reunion Weekend. Could you speak about what you will be showing them?

After the fantastic semester when the book was released I taught the Civic Caesura studio with Peter Schubert, Francois De Menil, Daniel Meridor and Dan Sherer.

I thought that it was important to install the arcade at a level of refinement that I imagined equal to Tiffany’s windows since the student work was worthy of it, and the west façade of Cooper has a new wide esplanade and planting, that makes it manifest in a manner that I concentrated on as a consulting architect for the Working Group and as Master Planner.

So we built the presentation volumes which allow the models to be seen from inside and the street simultaneously and with the generous donation of Professor Shubert, we were able to afford the additional wood, lights , etc above the budget we were allotted . We did this because we all believed it was the first time our school would be seen from the new surroundings and had to have the dignity and care with which we conduct our studio. The projects really take on Manhattan- each a site on an avenue based on accomplishments of an implicit continuous space on different types of avenues exemplified by Seagram, Lever and Rockefeller Center. Our studio projects took on the future of public space and continuity at the New Whitney, the Asia society, PJ Clarks , the Farley Post Office Penn station complex, the United Nations and others.