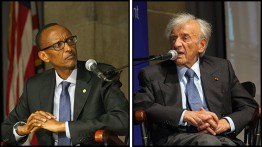

Elie Wiesel and President Paul Kagame of Rwanda in the Great Hall

POSTED ON: September 30, 2013

Elie Wiesel, Nobel laureate and world-renowned witness to the Holocaust, and Paul Kagame, President of the Republic of Rwanda, who is credited with ending the 1994 genocide there, appeared together on the stage of The Great Hall in front of a capacity crowd this past Sunday evening. The event, which was not without some controversy, drew an unusual mix of East African and Jewish-American audience members, with hundreds turned away at the door, according to David Greenstein, Director of Public Programs at The Cooper Union.

The discussion, entitled "Genocide: Do the Strong Have an Obligation to Protect the Weak?" took place concurrently with the opening weeks of the 68th session of the U.N. General Assembly and was described in invitations as a "prelude to the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide and the international response to the Syrian chemical slaughter." The event was sponsored by the Bronfman Center at NYU and This World: The Values Network, whose Executive Director, Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, moderated. You can listen to the conversation by clicking here (or right-click to download). Rabbi Boteach begins by asking Elie Wiesel, whom he calls "Rebbe Eliezer," about the story of Cain and Abel.

Topics included the failure of the U.S. to prevent both the genocide in Europe during World War II and the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. "One lesson we learned along the way was not to dwell so much on blaming others for what has happened or has not happened but to take responsibility for ourselves," President Kagame said. Touching on the topic of the chemical gassing of civilians in Syria, President Kagame voiced caution noting, "you have to be clear about who is responsible." Prof. Wiesel on the other hand bemoaned the "failure of Jewish leadership," in response to the gassing. "The moment we knew they were using gas we should have organized a mass demonstration," he said. Other topics included how to respond to Iran's recent change in tone, the role of Israel in the world and more philosophical questions such as whether to hate evil. "I believe in anger. Hate is not the answer," Elie Wiesel said.

The event provoked some controversy when Paul Rusesabagina, of Hotel Rwanda fame, posted an open letter to Rabbi Shmuley Boteach stating, in part, "It would be a terrible shame to see Elie Wiesel sitting at the same panel with someone accused by the international community of having killed hundreds of thousands of people in Rwanda’s neighbor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo." The reference is to Rwanda's support of M23, a rebel group in Eastern Congo whose actions were condemned by the U.S. State Department in August for resulting in, "civilian casualties, attacks on the UN peacekeeping mission (MONUSCO), and significant population displacements." Early in the conversation an audience member stood up and challenged the panel on the subject but was quickly escorted out. Later Rabbi Shmuley Boteach asked President Kagame directly about Rwanda's support of M23. "The issue of M23 … doesn't have much to do with the problem of genocide" President Kagame replied. "It has more to do with the failed state that Congo is and has been for many years."

The discussion ended with Elie Wiesel considering the responsibility of people towards the suffering of others, and by extension the responsibility of nations. "The main purpose is to believe we are not alone here," he said. "And therefore I must be ready to deal not with my loneliness but with my fellow man's loneliness. There is one sin that I refuse: to allow another person who suffers to think that nobody cares. That is the worst thing that could happen. That is my fault. If I don't speak up and take his or her hand, it is my fault. I think that is the basic principle of morality: to think of the otherness of the other."