Cooper 'Construction Crew' Writes Book about Architectural Materials

POSTED ON: March 11, 2016

This month, powerHouse Books released Construction Matters (2016), a book by Prof. Georg Windeck about the ways that architects use specific materials and technological innovations to create new types of forms. Collaborating with three former students—Lisa Larson-Walker, Sean Gaffney and Will Shapiro—as well as artist and designer Leah Beeferman, Prof. Windeck set out to create what he calls an “anti-textbook.” Instead of providing a purely technical approach to understanding materials, their properties and limitations, the group has used case study buildings to demonstrate how materials and construction inform architectural expression.

“Usually these technical issues are discussed in a very dry manner. But they can be very inspiring if seen against the background of the beautiful things that can be built with them, things that are fun about architecture,” said Prof. Windeck.

The book is divided into four chapters, each focusing on a particular construction method: brick masonry, thin shell concrete, steel framing and composite wood. Although Prof. Windeck and his co-editors could have chosen many more material technologies, they decided to focus on these four ways of building, as they demonstrate a diverse spectrum of different tectonic expressions. “The case studies are selected based on the idea of what’s an example that’s a very direct formal expression of a particular technology,” he said.

The idea for the book came about when, in 2008, Prof. Windeck decided to sit for the architectural registration board exams, that test an architect’s knowledge of structural design, construction methods, mechanical systems and other subjects. While studying, he thought about how the History of Architecture classes and design studios he was teaching at Cooper could be enhanced by presenting building materials not in isolation but as conduit’s for an architectural idea. To that end, he developed several seminars such as Face-Off and The 20th Century in Detail, that let students examine specific ways that technological advances were deployed by particular architects for expressive purposes. For instance, for the Monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe combined rubble brick with reinforcing steel to project parts of the wall forward. By creating cantilevering wall segments of different depths—a feat only possible with steel-reinforced masonry—Mies transformed a traditional brick wall into a cubist sculpture that created the illusion of a waving flag.

Ms. Larson-Walker, who graduated from the School of Art in 2009, had taken one of Prof. Windeck’s seminars and found that his approach shed light on her approach to art making. “What Georg set forward was a realization of core principles of modernism that I had never been able to wrap my mind around in any other approach, from sculpture, or design, that felt revelatory.”

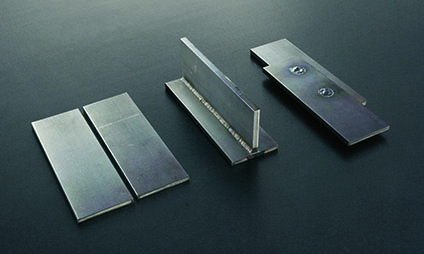

Many other students were energized by the lectures, so much so that several suggested he apply the framework of his lectures to a book. Prof. Windeck decided that if he could find a team of collaborators who would work with him to shape the book and create its supporting photos and drawings, he would take on the challenge. Ms. Larson-Walker, Mr. Gaffney and Mr. Shapiro started meeting with Prof. Windeck and slowly began fashioning the text and illustrations. Besides the core group, they found others willing to commit time to some aspect of the book: Ms. Beeferman who did the book’s graphic design and filmed the group’s Kickstarter video; Dennis Gilstad, a 2012 School of Art graduate who traveled in Japan to take photos of case study buildings; Ivan Himanen, a 2010 School of Architecture graduate who took photos in Finland; and Joseph Vidich, a metal fabricator who manufactured welding samples that are used as illustrations in the steel chapter (see photo above). “A lot of the material is supported by a larger community,” Prof. Windeck said.

Shapiro, who as the primary text editor was in charge of the book’s organization, noted that that meticulous and clear approach the group took came in part from the discipline of architecture: “The rigorous conceptual foundation in design that an architecture degree from Cooper provides was indispensable in thinking through and refining the arguments made in the text,” he said. Learning how to collaborate was equally critical.

Ms. Larson-Walker said that over time she found her most important contribution to the project was defining the book’s overall structure “to give guidance away from it becoming a technical manual, or becoming mired in a vernacular of architectural criticism.” Larson-Walker, who is Associate Art Director at Slate, wanted to transfer her own excitement about the subject to all interested readers, not just architects. At the same time, the process taught her the importance of economy and clarity in writing: “It was a bit of a look in the mirror for me to check my tendency towards empty but occasionally impressive grandiloquence in writing as an artist. At the same time a lot of what remains in the phrasing and tone of the book helped to get at the fruit of the fairly poetic sentiment I had for the ideas Georg had conceived.”

However poetic the sentiment may be, Prof. Windeck’s thesis—that understanding materials and construction methods must be understood in relation to the forms of expression they allow—is essential to good architecture. Sean Gaffney, a 2012 Chanin School of Architecture graduate who made the book’s drawings, emphasized that Construction Matters is not meant to be exhaustive, but use a small number of case studies to demonstrate the influence of construction technology on architecture. He said, “The observations made in the book are intended to be thought provoking—to be used as a tool for framing what has been accomplished in the past and how to approach solving related problems in the future.”

Mr. Gaffney, who works as an architect in New York, wanted his drawings to convey those observations as clearly and succinctly as possible. “The drawings are primarily line drawings, which utilize varying line weights to help them read spatially and highlight certain concepts found within the text,” he said. Prof. Windeck added, “Most construction details that are published in books and magazines show many secondary layers of information that distract from the core idea of what the detail really is about.”

Printing the book itself became an exercise in learning about materials: The group was determined to create a book that eschewed a glossy aesthetic yet included diagrams, text and photographs in each chapter. That turned out to be a tall order since photos tend to reprint less clearly on matte pages. Often the solution is to separate text from photographs, which are placed in a folio section. But that countered the goal of the book to make the specific details of construction as clear to professional readers as to neophytes by keeping relevant text, drawings and photos near each other. Leah Beeferman’s design for the book, which resembles in parts the black-and-white, industrial aesthetic of Hilla and Bernd Becher, was essential to the book’s visual and textual legibility. “Leah really took all the raw content that we generated and laid it out beautifully in the end,” said Mr. Gaffney. “She was a key part of the team.”

Prof. Windeck continually emphasized how much of a collaboration the book was, and the whole team reported that the collaborative aspects of the project were particularly gratifying. Mr. Shapiro currently teaches in the architecture school and is Head of Research for Analytics at Spotify. He found that the effort that went into Construction Matters mirrors his professional life in that both require considerable interdisciplinary interaction. He pointed out that in working on the book, “we each brought unique skills to bear on the process. My previous studies in mathematics, literature and semiotics, for example, or Lisa's grounding in art and art history.”

Ms. Larson-Walker concurred: “I'm absolutely certain that my transition into working in media (and all of its assorted responsibilities/tribulations not seen in what I knew of a studio practice) was eased by sharing time with a team that was so hardworking, methodical, and ultimately fun. There's a bit of comedy of seeing how my byline for the book has changed over the years (artist, writer, photo editor, art director) but undoubtedly I can relate both the material of Construction Matters as well as my time spent working to make it a reality as being an imminent part of my evolving creative and professional existence today.”

In some ways, the book presents a model of what Prof. Windeck would like to see more of in education, that is greater integration across disciplines. “When I teach History of Architecture I Antiquity, it’s important to introduce to students the social and philosophical framework of the mindset of builders of that particular time, but I also talk about technologies,” he said. “It’s a matter of getting the students really excited about these thought processes that do not isolate the different domains of architectural education. That’s the point of the book: at the end of the day, choosing a way to build, is like choosing a certain form of artistic expression.”