Dore Ashton Remembered

POSTED ON: February 2, 2017

Dore Ashton, professor emerita of art history in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS), art critic, historian and personal witness to the emergence of post-WWII American art, passed away this week. Beloved by students as much for her living history as for her interest in them, she taught generations at The Cooper Union starting in 1969 until just a few years ago. During her tenure she was also head of the School of Art from 1972 to 1976.

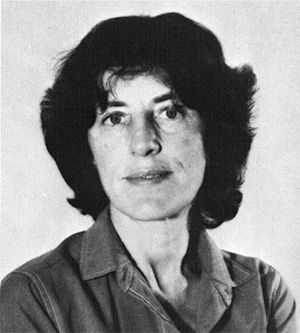

Dore Ashton (1952) Alice Neel. By kind permission of the Estate of Alice Neel © Estate of Alice Neel. All rights reserved.

Dore Ashton (1952) Alice Neel. By kind permission of the Estate of Alice Neel © Estate of Alice Neel. All rights reserved.

"Dore Ashton was able to convey, vividly and with critical eyes, an experience of art that it would be hard to imagine anyone else alive being able to do," William Germano, dean of HSS, says. "She knew everybody in a long and crucial generation… all the artists. She was able to tell students what Jackson Pollock did when she was in the room."

She liked to say she was the daughter of a doctor from Newark. Born in 1928, she received a B.A. from University of Wisconsin - Madison in 1949 and went on to earn a Masters in art history from Harvard in 1951. Around that time she became involved in the emerging New York Abstract Expressionist milieu, not as an artist but as an active observer and cultivator of relationships with the major participants. She covered the scene for the New York Times in the 1950s and went on to write or edit more than 30 books about the personalities and works that would become part of the art history canon, including The New York School: A Cultural Reckoning (1972) and About Rothko (1983).

"She was a force of nature in chronicling the pulse of American Art after the war,” Dennis Adams, professor in the School of Art who first met her in the mid 1980’s, says. “I'm 68. You were not considered educated in the visual arts in my generation if you hadn’t read Dore Ashton. Stephen Greene, my professor at the time said, 'When you get to New York you’ve got to get to know Dore.' I never had the nerve to call her up at the time.”

She was a complex and multi-faceted individual, described by those who knew her as a teacher or a colleague at The Cooper Union as, "smart," "sassy," "outspoken," "progressive," "cantankerous," "nonconformist," and "tough as nails" but also "gracious" and "a joy to be around."

Everyone agrees she would not want to be called a feminist, or even have anyone make anything of her remarkable position as one of the few women who played a role in the emergence of the storied New York School of painting. "She hated labels," Cynthia Hartling A'84, administrative associate in HSS and a former student of Professor Ashton's, says.

Dore Ashton in the 1974 Cable

Dore Ashton in the 1974 Cable

"What I loved very much was the difference between seeing her in the hallways and seeing her at home," Professor Adams recalls. "She basically didn't like institutions. She was from a free-wheeling café culture that flourished in New York after the war where you talk about ideas. She had always been an academic but she didn’t evolve into its posture. She didn’t want to be a part of those folks with PhDs. She felt she came up by her own bootstraps and walked the earth on her own dime. But at her home she was totally lovely and gracious. She sported a cigarette holder and was dressed to the nines. It was a salon of sorts. She was carrying that party, symbolically, as a figure. There could even be some enemies in the mix, or people she argued with, but the graciousness of her as a hostess... That she did very, very well."

She ran her classes in a similar fashion. Won Cha A'14, who would later become her last assistant, recalls her teaching style: "She would take out a very old folder with her course plan that was maybe five sentences of what she wanted to talk to you about that day. Then she would take out a cigarette, light it, take a really deep drag, look at all of us and ask us what our philosophy on life is. As 19-year old kids we were intimidated. Some of us were intrigued. That was Dore. She was challenging. She was determined to teach as she believed teaching is. She was intellectually rigorous but she also listened. She would never impose anything on to you unless you were interested. Dore was this amazing source on all these influential writers and artists that she personally knew. So she expected you to ask her questions, like 'What did Rothko eat for breakfast?' She would tell you that he was too hung over for breakfast."

Students "flocked" to Dore Ashton's classes, according to Dean Germano. In her later years she taught "Moments of 20th Century Art," that had to be broken into two sections it was so popular, and a course she called "Synartesis," a word she made up as a way to talk about many different things. "I took every course I could eat up. I adored Dore," Cynthia Hartling says. "In classes, she loved discussion but we were also expected to submit papers throughout the course. What was lovely was that she actually wrote comments that were very informative, making a myriad of other connections for each of us to pursue."

Dore Ashton stopped teaching in 2014 due to her health but managed to compile her papers for inclusion in the Smithsonian archives. She returned to The Cooper Union for one event, in The Great Hall. Homage to Dore Ashton, in December of that year, celebrated her work through many invited guests. It included a short film about her by Alfredo Jaar. In it she does much of what she was known for, sitting with a cigarette, recollecting the people she knew through the lens of her critique ("I was a great admirer of Philip [Guston]. I thought from the minute I saw his work that he was a real painter painter.") and espousing the causes she believed in ("I was and am, with a small 's,' a socialist"). The film ends as she flicks ashes into a tray. "What a time," she says. "What a time."