Senior Snapshots: Architecture 2020

POSTED ON: May 11, 2020

Jeremy Son, Kayla Montes de Oca, and Helmuth Rosales, all fifth-year students in The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, took the time to speak with us as they prepared for their thesis presentations held on May 5 and 6. Working from their homes in Brooklyn—Kayla and Helmuth in Bushwick, Jeremy in Bensonhurst—all of them had chosen thesis projects that explored the impact of movement and time on materials and, especially in the case of Kayla’s project, on the human body.

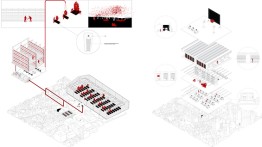

“I’m interested in bringing the body back into the aspect of the memorial,” the Miami native said. Noting that space is increasingly scarce for burials, she set out to find ways for the body to be recycled and act as nourishment for the landscape while the deceased is remembered not just by family and friends but by a community at large. She said, “I’m thinking about a way for the body to play an active role in the memorial and then, in a sense, giving back to the city.”

With that aim, Kayla investigated existing technology to convert corpses into compost or fortified liquids that can be used to nourish New York’s green spaces. These contributions to a community’s ecological health will be memorialized in an archive available in branches of the New York City public library system. Any visitor will be able to access information about the deceased—their biography as well as what use their remains were put to and where.

If the project is reminiscent of the 1973 sci-fi classic, Soylent Green (Charlton Heston uncovers a corporate plot to convert human bodies to a protein drink), it’s also prescient of the tragic loss of life due to COVID-19, and New York City’s inability to handle the volume of deaths in such a short period.

For his thesis project, Helmuth Rosales, who was a classmate of Kayla’s at DASH, an arts high school in Miami, was equally intrigued with recycling, albeit more abstractly. He designed L.I.T.T.E.R.Bu.G., a work of inflatable architecture meant to bounce over Freshkills Park, a 2,200-acre Staten Island park built over an infamous landfill. (The name is a tongue-in-cheek homage to NASA naming traditions; it stands for Lightweight Inflatable Trans-Temporal Extended Range Bubble on the Ground.) Noting the intermittent interest in inflatables—from the United States military to counter-culture collectives like Archigram and Ant Farm — Helmuth said, “There's a history to it. It comes and goes in waves, and when it shows up, it's very popular and almost trendy. But whenever it comes around, it's always very much about architecture in the environment and about new mediums, and how architects can do things in different ways, to have different spatial and material effects on the environment. And then it kind of disappears for a little bit and you go back to making things out of concrete and drywall.”

Unlike Rover in the British spy drama, “The Prisoner”— a massive balloon prone to smothering disobedient humans—Helmuth’s inflatable has been designed to gather information relevant to the environment at Freshkills, recording myriad elements including the gas released from the landfill, the returning flora, and the interactions of animals and humans on the site.

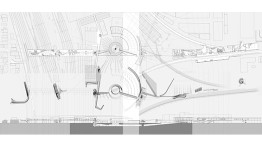

While Jeremy’s thesis also explores the interactions of living organisms and urban space, his is set in a decidedly more trafficked environment. Introducing a sort of promenade at a transportation hub in Kyoto, Japan’s original capital and a city of great importance in the nation’s history, Jeremy’s project looks at commuting as a type of modern-day ritual.

Essential to his thesis is an idea of the philosopher Byung-Chul Han, who has argued that in technologically advanced societies, people are driven by time efficiency and the constant pursuit of self-fulfillment. As time passes, we perceive it as moving at an increasingly greater speed and push ourselves harder to reach an elusive goal. Jeremy, a native of Hong Kong, wanted to reflect on Han’s ideas as they expressed themselves in an urban context. “So, it's not just the philosophical or abstract topic I'm trying to explore, but the very physical manifestation of it,” he said.

Setting out to slow down our perception of time, Jeremy first examined the elements of a Japanese tea ceremony with a set of drawings he made into a stop-action video. As his thinking progressed, he applied architectural techniques such as collage of plans and drawings to understand the Kyoto site and introduce a pathway that connects neighborhoods and institutions to a local commuter station. His design works “on the urban scale that serves infrastructurally, but creating a new form of spatiality and intimacy of linear time experience.”

All three adjusted to a thesis review that would happen virtually, but not without some regret. To facilitate the move to an online platform, the studio professors gave students the option to present virtually or to work on a portfolio or both. Helmuth chose to submit a portfolio and build a web site, still in progress, that approximates the actions of L.I.T.T.E.R.Bu.G in the future, specifically May 2070. “It was a difficult decision to not present this week, he said, “but my project was worked on with the goal of building something full-scale and operable. With that option more or less erased, I appreciated the time and flexibility to recalibrate the project to other mediums, like the website.”

The three classmates agreed that the review experience, despite being virtual, was a fulfilling one. Jeremy, who hopes to start his new job at the architecture firm Allied Works as soon as quarantine restrictions are lifted, said, “The presentation went very well; it was very productive and celebratory. Very glad to have a great jury, with professors that guided me through the past five years in different studios and on other occasions.” He was particularly grateful to the ongoing input of Dean Nader Tehrani, who, he said “has always been critical about my work and provided me exceptional experiences and opportunities in the past few years. He pushed me and my work to new horizons.”

Though Kayla had to adapt her drawings, which she made on a 27” computer monitor, for an audience using laptops, she felt invigorated by the discussion and took comfort in seeing her colleagues of five years “share one last review together,” as she put it. For herself, she said, “The final review wasn’t an end, but a beginning into a body of work that I hope to work on for years to come.”

Helmuth, who like Kayla, is now investigating future job and internship prospects from the safety of his apartment, agrees but notes that the circumstances engendered by COVID-19 demonstrates “that we’re operating under very real restrictions….”

His assessment of the current state of the world is thoughtful and reflective of a person who, like his classmates, is looking to have an impact on our future environments: “There are upsides and downsides to this situation though, and everyone is learning a lot by simply living through it. I think optimism is very important, but it is just as valuable to acknowledge what we are indeed losing under these circumstances, if only so we can better appreciate them later.”